KATHMANDU, Nepal—The Boeing 737 loaded with relief supplies and caregivers touched down at Tribhuvan International Airport six days (nearly to the minute) after the first of two cataclysmic earthquakes wrecked havoc on the tiny Himalayan nation of Nepal.

Joining me aboard the flight from Singapore were a few other journalists from the United States and Europe, a team from the China Lingshan International Rescue in their distinctive fire engine red uniforms, and several dozen surgeons from South Africa who had come to Nepal with Gift of the Giver organization, an NGO founded in 1992 by a Sufi sheik from Istanbul.

Among us were Christians, Hindus, Muslims, Jews, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains—people of good will of many religious traditions and none at all. What we had in common was a desire to help the gentle people of Nepal (one of the poorest nations in the world) who had suffered through the devastation of an earthquake on April 24 so massive that it actually moved the global satellite positioning of its capital city by nearly 10 feet.

For some of us, that assistance took the form of pulling corpses and a few miraculous survivors from the concrete and brick ruins of homes, businesses, and even houses of worship leveled by the first earthquake. (A second earthquake of nearly the same size—7.3 on the Richter scale—struck Nepal on May 11, the day after I returned to California from Nepal.)

Others—the healers from Africa and elsewhere—would offer relief to the traumatized during grueling shifts in Nepal’s overwhelmed hospitals, in surgical theaters, setting broken bones, stitching wounds, and compassionate bedside care.

Interspersed among us, undoubtedly, were those hoping to offer some kind of spiritual aid, solace, or direction to the Nepalese. In generations past, we might simply have labeled this cohort “missionaries,” visitors hoping to share their version of the gospel truth with the broken and brokenhearted.

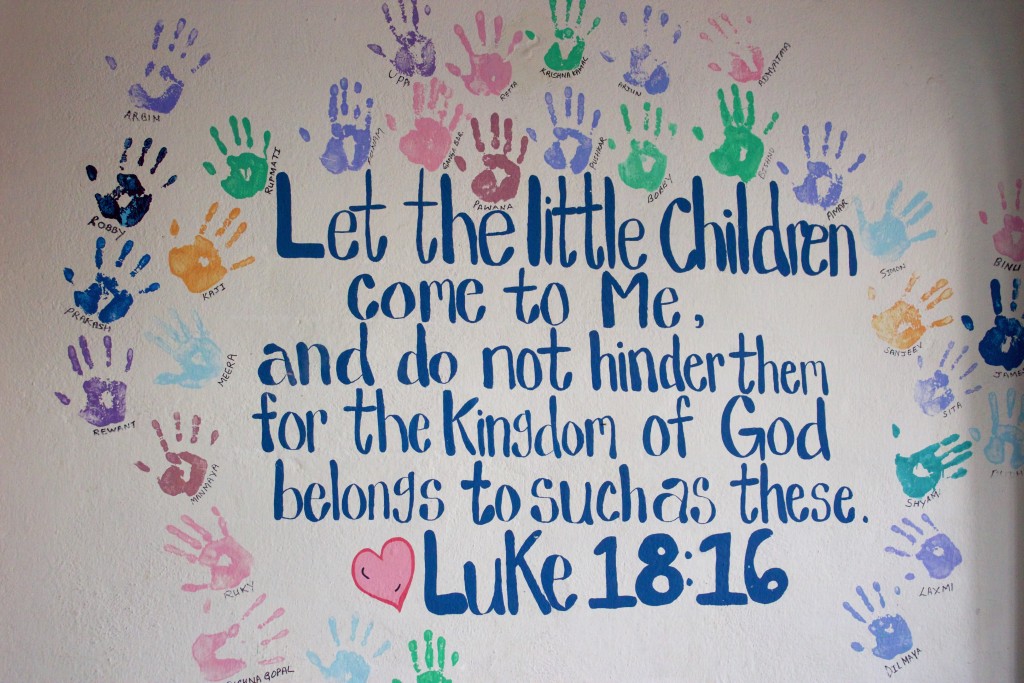

A Bible verse and hand prints of many of the more than three dozen children who live there decorates a wall at Mendies Haven, the orphanage outside Kathmandu run by Charles Mendies’ family for 60 years. Photo by Cathleen Falsani.

Instead what I encountered time and again during the eight days I spent in Nepal earlier this month was a decidedly different take on evangelism and the idea of “mission,” one that bears little resemblance to the “cold contact witnessing” model I learned on a teen missions trip nearly 30 years ago. (It would have been more effective literally to throw Bibles at the heads of unsuspecting passersby than it was to accost complete strangers with questions such as “where would you spend eternity if you died tonight” or “do you know Jesus as your personal Lord and savior”?)

“We are beginning to see a paradigm shift,” Charles Mendies told me during our conversation at a busy Kathmandu hotel as bigwigs from faith-based NGOs mixed with members of USAID, the United Nations, and Medicins Sans Frontières on the nearby veranda.”By and large the mission has changed.”

Mendies would know. Born in Nepal to a Canadian mother (who had come to India as a Christian missionary in 1946) and an English-Burmese father who reared him as an evangelical Christian, in 1989 at the age of 34, Mendies was found guilty of “proselytizing” (in this case, placing bibles in Nepali hotel rooms) and spent six months in Kathmandu’s Central Jail, where he shared a cell with 17 other prisoners.

Nepal’s intensely complicated political heritage has been aptly described as a journey from “oligarchy, monarchy, to obstinately unstable democracy.” The formerly Hindu kingdom is now a secular state, but controversies about the role of religion in government persist and an interim constitution (in place since 2007) still prohibits proselytizing.

“I think it’s an evolutionary process,” Mendies told me. In the 70s and 80s, he explained, “we took western theology, packaged it, labeled it Christian, and we took it here and said: We’re going to make Christians. We brought western theology, not Christianity.”

As Mendies sees it,the priorities of old-fashioned evangelism—where a premium was placed on the number of souls that were “saved”—have been supplanted in recent years by those of the social gospel, in which Christian ethics are applied to societal issues such as poverty, violence, preventable disease, ecological concerns, gender issues, and human rights.

“More and more you are beginning to see people seeing the social aspect of the Gospel, where Jesus himself went out and ministered and touched people,” he told me. “Going out and just preaching isn’t cutting it,” Mendies said. “We need a new interpretation of what Christ told us. The verse says, ‘the harvest is ripe but the laborers are few,’ and we tend to stop at that point. But if you read the whole verse, it says, ‘Pray ye therefore the Lord of the Harvest that he will send forth laborers.’

“As far as the social gospel is concerned, I’m seeing it across the board,” he said, including among many of the more than 300 Christian congregations in the Kathmandu area alone. “That is where, I think, we are beginning to see a paradigm shift in missions today.”

“It makes me very happy to see because one of the indictments against the church in the developing world has been so-called ‘rice Christianity,’ and to be honest, there was a lot of truth to that,” Mendies said.

‘I went for friendship’

Chris Heuertz visits with some of the younger members of his longtime friends, the Rai family, in Kathmandu on May 1, 2015. Photo by Cathleen Falsani.

Chris Heuertz, co-founder with his wife, Phileena, of the Gravity Center for Contemplative Activism in Omaha, Neb., arrived in Kathmandu about 30 minutes after I did on May 1. It was Heuertz’s 21st visit to Nepal, where for 20 years he and his wife worked on behalf the poor and vulnerable, particularly women and children victimized by human traffickers in the commercial sex industry. For many years, the Heuertzes did that work through Word Made Flesh, a Christian organization that believes in a “holistic” approach to ministry, where “we recognize the world suffers from both physical and spiritual hunger. Our ministry is to satisfy those hungers by offering the bread of loaf along with the Bread of Life.”

Meeting up in Kathmandu with Chris, a friend of several years, was completely serendipitous (if you believe in such things). I had planned to travel to Nepal with a small Fair Trade NGO based in Laguna Beach, Calif., where I live, and was set to depart about 12 hours after the first earthquake hit on April 24. The NGO’s plans understandably changed, but after some prayerful contemplation of my own, I decided I still should go as an independent journalist. I understood my mission (in the spiritual and every other sense) to be simple: to be a witness, to do whatever I could to help in whatever way I was able, to listen, to hold space for people who were suffering, and to tell stories.

I pushed back my original departure by four days, and as the time to head for the Himalayas drew closer, so did a growing sense of anxiety about making the journey alone with only a few connections on the ground. As my courage began to wain, I got an email from Chris: “Yo! I leave for Kathmandu Tuesday.” (I was flying from Los Angeles on Wednesday.) “I’ll only be in Nepal for six days, but would love to introduce you to my local friends there.”

I could have cried. (Actually, I did a little.) Heuertz might help me make the connections I likely wouldn’t be able to make on my own. A few days later, in the frenzy of the Kathmandu airport with scores of tourists trying to get out and battalions of aid workers trying to get in, we found each other and shared a taxi to an off-the-beaten-track hotel around the corner from where he was staying with friends not far from the Swayambhunath Temple famous for its historic sacred buildings and roving bands of ill-mannered monkeys.

Pastor Gautham and Rekha Rai in the living room of the home they share with 25 other family members in Kathmandu on May 8, 2015. Photo by Cathleen Falsani.

Over the course of the days that followed, I got to know Heuertz’s friends: a family of Nepali Christians—27 of them in one tall, blessedly sturdy house—led by Gautham Rai, a 42-year-old pastor who emigrated from Bhutan when he was a child, and his wife, Rheka, who have adopted or otherwise given a home to a number of girls and young women who have survived sometimes horrific abuse and neglect.

“I’m just here to be here,” Heuertz would say apologetically from time to time during our visits in and around Kathmandu, as if showing up and being fully, lovingly present weren’t a robust enough mission. “I just wanted to come and support my friends, to show them I love them, and be here for whatever they need.”

He played tag on the rooftop of the Rai home with three little girls—Joanna, Ellie, and Aksha—running barefoot between laundry drying on the lines. He held two-month-old Mariyanna for hours on end, rocking her in his arms as the older children played card games or cuddled around him. The Rai family invited me to join them for meals with the whole family seated on mats in a circle on the kitchen floor.

We ate. We talked. We laughed. We prayed. We connected. And somewhere in our time together, something shifted. If there was a heaviness, it lifted. Some might describe it as the Spirit moving, as it does, and knitting back together the broken bits of each one of us.

“The Rai’s selflessness is unmatched; their hope-filled drive to re-build a better world is totally inspiring,” Heuertz wrote after returning to the States a few days before the second quake hit Nepal. “We are not here without reason. We have a divine purpose. This affirmation was made clear each day when I held and rocked a beautiful little baby girl to sleep for her morning nap.”

Three Guys from Wisconsin

Ruins of a church in the rural foothills of the Himalayas outside Kathmandu where the Wisconsin guys brought relief supplies earlier this month. Photo from VisionNationals.org.

I heard them before I could see them.

One morning early on in my Nepalese sojourn, I heard the distinctly flat-accented voices of men from the American Midwest waft up from the street through an open window in my second-floor hotel room. One of the voices belonged to Heuertz, but the others I didn’t recognize.

A few moments later, I encountered three big middle-aged guys from Wisconsin with rucksacks strapped to their backs, dressed like a cross between trekkers and construction workers, which is, essentially, what they were.

Mitch Lown, Johnny Kruger, and Chad Clark—three friends from LaCrosse who, because of their Christian faith, felt called to come to Nepal to help in whatever way they could, just as they had a few years ago after the devastating earthquake in Haiti.

They didn’t have a plan and only a few local connections, but they showed up with their tools and their skills and a willingness to work. There was never a whisper of sneaking Jesus in the back door, if you will, of making the help they were offering be about anything more than the work of their hands.

They pitched in helping organizers at a “tent city” in Kathmandu for people who’d lost or been forced from their homes after the quake, patched concrete at buildings that are part of a Christian-run school in the capital city, and traveled a couple of hours away higher up in the rural foothills of the Himalayas to bring relief supplies to a community where a church and many homes had been flattened by the quake.

“As a Christian guy I have always held tight to the fact that it is better to give than receive,” said Lown, a one-time shop teacher who now works in construction and real estate. “I also have a problem with the way the church in America spends money and I felt that my money could go further by me putting it to use for good. I also really like to travel, have fun, and meet new people.”

Kruger says it was “blind faith” that got him on a plane to Kathmandu less than 24 hours after one of the other guys suggested he should make the trip.

“My faith drives me to love everyone,” Kruger said, “and to show that love through my actions, with the understanding that I am no better for my faith or experience/knowledge. That is the ideal, not always easily practiced.”

Love, Forgiveness, and Compassion

Children at Chhahari children’s home in Kathmandu, play spirited rounds of the card game Uno a week after the April 24 “Great Earthquake” struck Nepal. Photo by Cathleen Falsani.

Enamored since childhood with the fictional Tibetan lamasery Shangri-la from James Hilton’s 1933 novel Lost Horizon and Frank Capra’s film adaptation of the same name, in 2003, Christine Casey decided it was time to fulfill her longtime dream of visiting Tibet. When ongoing issues between Tibet and the Chinese government made what her ideal trip virtually impossible, friend suggested she visit Nepal instead where a large population of Tibetan Buddhist refugees has lived since the 1960s.

Casey planned to spend three months in Nepal on a 21-day trek through the Himalayas between several weeks on either side of the trek to immerse herself in Nepali culture.

“The things I saw on the street here, I went, ‘holy God, I can’t even believe it.’ “People walking over children—naked children—in the street. You see it on TV in the States and you can turn the channel. But you can’t turn the channel here because it’s right in front of you,” said Casey, 73, who for the last dozen years has split her time between Kathmandu and Laguna Beach, Calif.

“So when I left here, I said, I’ve got to come back. My son’s a physician and he said let’s just focus on what you can do because you can’t do everything,” she said.

Yes, but what we can do we must do, I told Casey, recalling the wise words a friend told me years ago, words that eventually changed transformed my own life and family.

“Exactly,” she said, explaining how since that first trip in 2003 she spends five months a year in Nepal (the most allowed by her tourist visa) and the other seven months in California fundraising for Chhahari, the organization she founded that runs a home for about two dozen children in Kathmandu. Most of the children are “true orphans,” meaning both of their biological parents are deceased, while a few have a living parent but he or she is incapacitated.

“We raise the money in the United States and spend it in Nepal,” said Casey, who before launching Chhahari (which means “shelter” in Nepalese) sold as many of her belongings as she could, gave the rest away, and lives on Social Security in a 10-by-20-foot low-income housing apartment in Laguna. “I don’t really care about anything. I have my room there and that’s it. I don’t need anything else. I’ve had a good life.”

Casey is Roman Catholic but also has an affinity for Buddhism. “I don’t see that there’s any dichotomy there. I have that on my refrigerator—a picture of Thomas Merton and the Dalai Lama,” she said while a few feet away two clutches of Chhahari kids played spirited rounds of the card game Uno.

“I don’t spread Christianity,” she said decisively. “The children are Buddhists and Hindus and I don’t do that. They’ve asked me questions about Jesus and I’ve told them, well, this is the deal. My philosophy is, you can burn all the books…but if you have love, forgiveness, and compassion in your heart, that’s all you need. I’d wish that for everyone in the world.

“If you instill that in a child from an early age and show them by your actions and the way you live your life and how you treat other people,” Casey said, “I think that’s a job well done.”

Mission accomplished. I couldn’t agree more.