The slaughter of nine worshippers in a Charleston church once more forces us to have conversations we would rather not have. This was clearly an act of terrorism, as defined by the FBI, but we will not call it that because the perpetrator is not a racial or religious minority. He wanted to intimidate a group of people. In his own words, he killed people praying because they were black, but we will shy away from the conversation on race because we say we do not know enough.

The hard conversations are not just about who gets to be called a “terrorist,” or about racism in America. It’s also about the way in which accept and institutionalize violence as part of an Enlightenment story that both liberals and conservatives look to in defining their vision of the nation.

At times like these, American politicians and pundits turn to Enlightenment values like guarantees of freedom of religion and speech and the promise that all people will be treated as equals. These may be the ideals of the Enlightenment, but that certainly hasn’t been its only legacy.

What we call the Enlightenment is actually a collection of philosophical movements throughout Europe, spanning nearly a hundred years. While lauded for focusing on individual liberties, it was conditioned by the historical realities of the time; these liberties were not intended to be truly universal. The Declaration of Independence famously declares that “all men are created equal,” excluding women, while the US Constitution considers black people only 3/5th human.

Just as important, the Enlightenment and Reformation were about moving authority away from the Church to the nation-state. One of the defining aspects of a nation is determining who belongs to it. Anti-Semitism, for example, which has continued to exist since the Enlightenment, is no longer based on theology, but on the notion of the foreign invader threatening the nation. Some aspects of the Enlightenment, in other words, certainly didn’t stand in the way of the Holocaust.

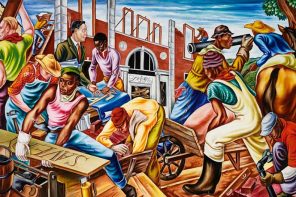

Ultimately, it’s about who gets to commit violence in a permissible way, and it’s always the nation. That violence can be directed at other nations, or to internal populations. One simply has to look at a film like Birth of a Nation to see how this works.

The way in which police tactics are used against black bodies in America is enabled by Enlightenment thinking in the sense that it’s a reflection of the different ideas of who is truly a citizen, and therefore who’s allowed the rights of protection of the state.

It’s not just law enforcement, but the entire penal system, from arrest to sentencing, which treats any minority as having fewer rights than the majority, a direct legacy of the slave period. It’s no coincidence that when the Trayvon Martin murder happened, and we saw a demand to recognize that black lives matter, that Dylann Roof became radicalized. His worldview, his place of privilege, was so shaken that well after Martin’s murder went unpunished, he was able to go into a church, pray with people, and then kill them.

That we do not officially call him a terrorist, or people like Joseph Stack a terrorist, is an implicit acknowledgement that we treat their violence as closer to accepted forms of violence than we would care to admit. What we call terrorism is actually a threat to the monopoly on violence that the nation exercises. After the first Gulf War, we did not encourage Enlightenment ideals in Iraq, we imposed sanctions and violence, directly and indirectly. That is the lesson that Iraqis learned from us; the Enlightenment realities of control and enforcement. It’s no wonder that we were not met with roses after the second Gulf War.

The difficult conversation we need to be having concerns our true ideals. We can keep declaring that it’s about the Enlightenment, but what part of that do we actually manifest? Our domestic and foreign policy have always been aligned around the issue of conformity and maintaining privilege. We cannot see the two as separate. As long as we have official policies that see parts of our population as less than civilized, thus less than citizens, and thus less than human, we will always see the world outside our borders in the same way.

If we believe that there are Enlightenment values that have meaning, we need to live up to those in practice, stop being shocked at everyday violence inside our borders, and do something that puts an end to it. Our number one export has to stop being weapons, because that too demonstrates where our values lie.

It’s time to start having these difficult conversations, and saying and living our ideals in a way that matters.