If Sunday morning at 11 o’clock is Christian America’s most segregated hour, then “Amazing Grace” might be its most segregated song.

To be sure, it is one of very few pieces of music instantly recognized all over the United States, by people of all races and even of different faiths. Sing the first few words in a public place and you can be sure someone around you will join in. You may even find youself leading a spontaneous choir. The same might be said only of the “Star Spangled Banner.” No other hymn will ever be the spiritual national anthem that “Amazing Grace” has become.

All of which makes it particularly striking to consider that “Amazing Grace” is not one song, but many. More than most pieces of music, its meaning is dependent upon the context in which it is sung or heard.

The American “Amazing Grace” spectrum runs from the painfully stilted (for example, when sung by Tom Netheron of the Lawrence Welk’s “Musical Family” ) to the effortlessly soulful (as in the hands of Reverend Al Green.) The difference between these approaches is ripe material for parody. “When white people sing Amazing Grace,” the comedian Rick Smiley riffs in astonishment, “you can understand the words. They sing every single syllable!”

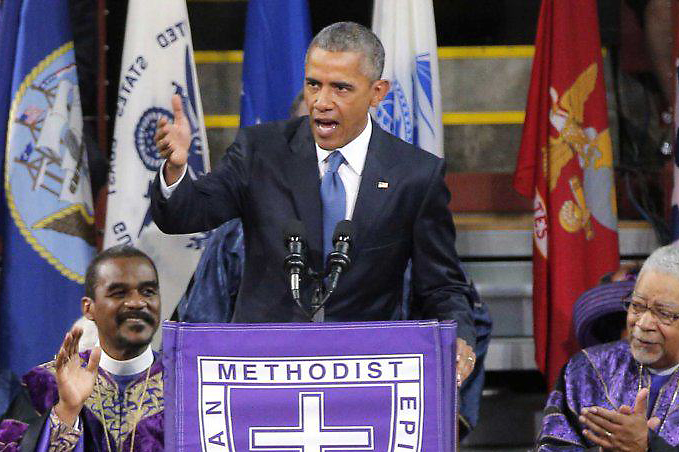

The “Amazing Grace” heard last week at the memorial service of Reverend Clementa Pinckney in Charleston was clearly part of the black church tradition. Barack Obama is no Al Green, but in the words of Questlove from the hiphop soul band The Roots, the president’s rendition included “the blackest blues note ever,” an echo of both the enduring significance of this English hymn to African American culture, and its apocryphal history as a melody born on a slave ship.

As the often told story goes, “Amazing Grace” was first published by the Christian minister and former slave ship captain John Newton in 1779 . In a popular Youtube clip, the gospel singer Wintley Phipps recounts that it was on a ship packed with suffering human cargo that “many believe [Newton] heard this melody that sounds very much like a West African sorrow chant.”

“It has a haunting, plaintive quality to it that reaches past your arrogance, past your pride, and it speaks to that part of you that’s in bondage,” Phipps continued. “And we feel it. We feel it. It’s just one of the most amazing melodies in all of human history.”

Phipps goes on to sing the song as he imagines Newton first heard it—all feeling, no words.

The only problem with the moving backstory that inspired this evocative rendition is that is probably not true. The melody now known and beloved as “Amazing Grace” joined Newton’s verses decades after he composed them. Without a doubt, many spirituals do have their melodic roots in pre-Christian traditions the enslaved brought with them across the Middle Passage. In its origins, at least, “Amazing Grace” was not likely one of them.

Yet the song’s power last week had little to do with where it came from, but rather the purposes to which it has been put.

Questlove was more than just musically correct when he called out Obama’s use of a “blues note.” The folklorist Gerald Davis often compared African American preaching to the twelve-bar blues, and suggested that each art, though vastly different in content, had developed similar ways of expressing virtuosity.

“In the twelve-bar blues,” he explained, “the basic pattern is always the same, a pattern that seems to repeat itself over and over again. Yet each instrument, including the human voice, is free to improvise as long as the pattern is not violated.”

“The preacher’s art is speech music,” he said. “Not music in the sense that it is chanted or has a musical quality. But that it is organized in much the same way that one composes music. It has rhythm and pacing, it has highs and lows. Like music, it is rigidly structured but seemingly spontaneous.”

The unexpected use of song within a spoken sermon is not unlike an ambitious solo that threatens the musical structure around it, but then brings it to a resolution that did not seem possible. Preachers who could pull off such feats from the pulpit, Davis once said, were regarded as the “word magicians” of the community.

Some kind of magic certainly seemed to be required to end a week of mourning with a moment of celebration. It was a moment that depended not only on “Amazing Grace,” but on knowing how to use it.