What inspired you to write After the Wrath of God?

Many years ago now, back in early 2000s, I attended a talk by Gregg Bordowitz. I was familiar with his work as an AIDS activist and artist and had long admired his powerful 1993 documentary Fast Trip, Long Drop. He was in Atlanta, where I was living at the time, to screen another film. One scene featured a man standing at a podium talking about his experience with AIDS, including his faith in God.

This image jolted me—I’d honestly never thought about religion and AIDS in that way, that is, about the religious lives of gay men with AIDS. I was more familiar with conservative Christian rhetoric about AIDS as a punishment for sexual sin, especially what they often refer to as sodomy, to use a legal and theological language, or homosexuality, to use a more positivist one.

After the Wrath of God: AIDS, Sexuality, and American Religion

Anthony M. Petro

Oxford University Press

(July 1, 2015)

When I got to Princeton, Heather White was already doing amazing work on the religious history of the gay rights movement, and seeing her do that project really gave me a sense of possibility for writing about religion and the AIDS crisis.

When I first started the project, I planned to focus on progressive religious responses to the epidemic quickly realized two things. First, “progressive” and “conservative”—the labels of cultural wars rhetoric—were too rigid to capture the history I wanted to examine. And second, I did not want to write a “good religion” book, which I feared emphasizing progressive religious responses might lead to. I hope After the Wrath of God captures the complexity of this history without falling into either trap.

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

For readers interested in religion, my key message is that the AIDS crisis changed the way American Christians talked about sexuality. Sex was by no means a new topic for Christians, but the AIDS crisis brought discussion of gay sex and of various sexual practices, like oral and anal sex, into virtually every household in the country.

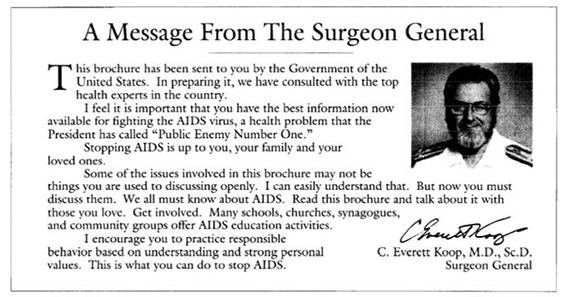

In fact, Reagan’s conservative aide Gary Bauer complained about just this! In the late 1980s, he trashed the (evangelical) Surgeon General C. Everett Koop’s educational pamphlet Understanding AIDS, which was mailed to over a hundred million families nationwide. Bauer and others complained that the flier flaunted sexual matters, including the use of condoms. He offered a more modest proposal for discussing sex education, one that avoided much of the specificity of Koop’s program and that emphasized the benefits of heterosexuality (and the immorality of homosexuality).

Over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, a number of Christian denominations and churches found that they really had to discuss the HIV/AIDS crisis, because it was a pressing local and national concern. And to do so, they had to talk about sex, including homosexuality.

It turns out, the things they had to say about AIDS and about sex proved far more diverse than Christian Right rhetoric pronouncing AIDS as “God’s wrath”—and far more pervasive, too. While American Christians disagreed quite a bit about sexual morality, a great majority of the Christian mainstream stopped short of castigating gay men and instead focused on the importance of abstinence and monogamy.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

I had planned to include a chapter focusing on debates over needle exchange among public health experts and church leaders, especially members of historically black churches who worked in areas where HIV was often transmitted through IV drug use. The chapter moved away from my focus on sexual morality in the rest of the book and opened up a host of complicated historical and cultural issues that needed much more attention than I could give them in one chapter. So I shelved it, at least for the book.

I had planned to include a chapter focusing on debates over needle exchange among public health experts and church leaders, especially members of historically black churches who worked in areas where HIV was often transmitted through IV drug use. The chapter moved away from my focus on sexual morality in the rest of the book and opened up a host of complicated historical and cultural issues that needed much more attention than I could give them in one chapter. So I shelved it, at least for the book.

There are several good studies that have since been published or that are in the works on the history of African Americans and the AIDS crisis, including attention to religion, that I wish I’d had access to when I was writing the book—work by people like Pamela Leong, Sandra Barnes, Stephen Inrig, Dan Royles, and Audrey Kerr. This new work definitely helps tell some of this history. And I plan to talk more about the history of moral debates over needle exchange in my next project on the history of religion and public health.

I also thought about including more material on cultural production that would have examined three plays: Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, one of the first plays about the early history of AIDS activism in New York City; Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, one of the most important and gorgeous plays about the crisis; and Yvette Heyliger’s What Would Jesus Do?, a more recent play about how members of an African American church in Harlem deal with HIV/AIDS in their congregation.

I was excited about the possibility of looking at cultural production in my epilogue, including how theatre in particular has served as a political and even religious site for so many gay men affected by the AIDS crisis. I left this discussion out because, again, it took away from the cohesion of the book as a whole. And with all the recent debates about PrEP (a pill that can be used to prevent HIV transmission) and gay marriage, I felt there were more pressing issues to engage—okay, and I figured maybe the plays were best left to theatre historians and performance theorists.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

I think one of the biggest misconceptions is that it is a “gay” story. Of course, a book could be predominantly a gay story and be perfectly worth reading. As it happens, though, much of my book is actually about nongay Christians discussing sexuality—including what they often considered “traditional” or “biblical” forms of sexuality (which they often just called heterosexuality).

They also talked a lot about improper forms of sex, including sodomy or homosexuality, but also sex before marriage, sex out of wedlock, and commercial sex. But even this history of sexuality is a starting point for a bigger claim about the form of power that religion takes in modern America, including its ability to shape ideas about health and citizenship.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

I had two immediate audiences in mind—scholars of religion in the U.S. and historians of sexuality (including historians of the AIDS crisis). These sets of scholars don’t often talk to one another, so I made a concerted effort to write After the Wrath of God in a way that would open this historical episode for both audiences.

I also tried to write for broader publics—especially for members of communities impacted by the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly those in lesbian and gay or queer communities, and also for Christian or other religious readers (many of whom are also lesbian, gay, or queer) who may want to know more about the history of Protestantism and Catholicism in this period.

I also wrote very much for my students. I had the privilege of teaching a seminar on religion and AIDS in the U.S. when I was still in graduate school and found students to be incredibly curious about this history. Their starting point for understanding the AIDS crisis is very different than that for those of use who lived through the 1980s and 1990s—students today more often associate AIDS with Africa and with poverty than with gay men and the Christian Right. But my students were fascinated by much of this earlier history of AIDS in the U.S., and it was such a joy teaching them.

So I also hope my book brings the history of the AIDS crisis to life for younger readers curious about this past—a past that, I argue in the book, continues to shape American sexual and religious culture as well as debates about public health.

Are you hoping to inform readers? or to entertain them? anger them?

Since the 1980s, several Christian writers, coming from liberal and evangelical traditions alike, have declared the AIDS epidemic one the most important religious events—if not the most pressing—facing American Christians. More than anything, I hope to engage readers in a discussion about the legacy of the AIDS crisis in the U.S., including how Christians have shaped how we think about the epidemic, about public health, and about what it means to be a good or moral American.

What alternative title would you give the book?

I toyed with “Beyond God’s Wrath” early on, but it didn’t have the right rhythm. I think the subtitle could just as well be “AIDS, Sexuality, and Moral Citizenship.”

How do you feel about the cover?

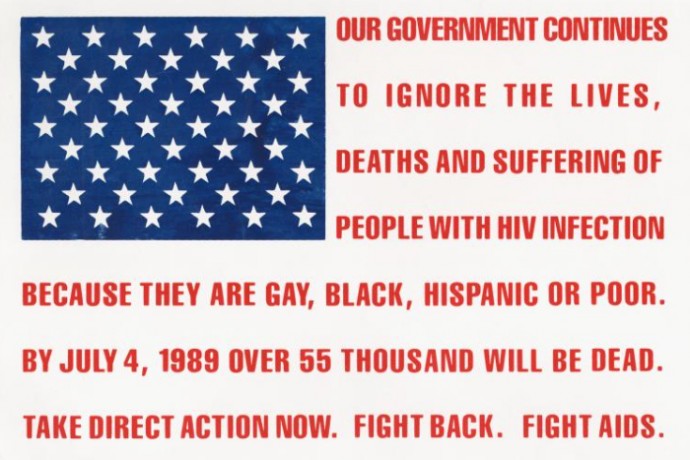

I love it! OUP did a wonderful job. The bright pink evokes Gran Fury’s Silence=Death sign, which became a symbol of AIDS activism in the 1980s and 90s, especially the work of ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), which is the basis of one of my chapters.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written? Which one? Why?

One of my favorite books in the field is Leigh Schmidt’s Hearing Things, which is historically and theoretically rich in addition to being beautifully written. And given that I work mostly on recent history, I admit to being a little jealous of historians working on earlier time periods!

What’s your next book?

My next project looks at the history of religious engagement with health and disability policy in the U.S. since the 1950s. It draws upon the methods of religious studies, along with feminist and queer disability studies, to demonstrate how Christian leaders and activists have shaped cultural understandings of health and moral citizenship.

I do this by discussing a series of topics, including alcoholism, euthanasia, disability, vaccination, and drug use. My hunch is that tracking how American Christians have shaped cultural understandings of public health, including the health of the nation, will show new forms that Christian power and influence have taken, even as the United States has become increasingly secular.

The project seeks to show how the postwar history of American Christianity and medicine is less a story of religious decline than one of transformation. The cases I discuss reveal ongoing negotiations between secular and religious forms of knowledge about bodies and about health that have advanced new understandings of personhood, moral citizenship, and Americans’ relationship to the politics of health.

At its broadest reach, my research asks how “health,” including public health, has become a central category through which American Christians have continued to shape moral conduct.