The following story doesn’t deal explicitly with religion and public life but RD has decided to run it for the following reason: When applied to the issue of same-sex marriage in America, the author’s essential argument—that “the great hidden truth of American constitutional law is that our law is determined by the wishes and commitments of the American people”—has everything to do with the prevailing winds in America’s religious landscape. The savvy reader will derive an implication here for political activism—that even when an issue is being fought in the courts it is public opinion that matters most. We hope that this article will spark a lively discussion. —ed.

In a 2002 Newsweek poll, 87% of Americans responded that the words “under God” should remain in the Pledge of Allegiance. Even with the increasing secularization underway in American society, well over three-quarters of the American people undoubtedly feel the same today. What should we conclude if 75% of the American people want the words “under God” to remain in the Pledge of Allegiance? We should conclude that the words “under God” are going to stay in the Pledge of Allegiance, Establishment Clause or no Establishment Clause.

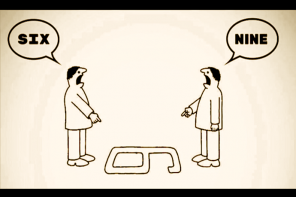

The great hidden truth of American constitutional law is that our law is determined by the wishes and commitments of the American people.

Sometimes the effect of public opinion on the courts is crude and political, as when the United States Supreme Court gave up its opposition to the New Deal after FDR’s 1936 presidential election victory. Sometimes the effect of public opinion is broadly cultural, as when the Equal Protection Clause was held to protect women against traditional discriminations that the framers of the clause thought were benign and natural and never intended to disturb. And sometimes the courts help change public opinion, as when the Supreme Court turned against Jim Crow in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision in 1954. But always, as the philosopher John Rawls once put it, “The Constitution is not what the Court says it is. Rather it is what the people… eventually allow the Court to say it is.”

At the Majority’s Mercy?

Judges and law professors despise the truth that the people decide the content of their Constitution. They like to pretend that the interpretation of the Constitution is a technical enterprise on which lawyers are uniquely qualified to speak. This pretense is as present on the left of the political spectrum, where the language of universal human rights is treated as somehow obvious and self-evident, as it is on the right, where the protections of the Constitution are said to be strictly limited by history and original intention.

But the interpretation of the people’s constitution is not a technical matter—nor is it a matter of logic. It is a matter of deep political commitment; it is inescapably a matter of public struggle and engagement.

These thoughts come to mind in light of the arguments earlier this month in the California Supreme Court over the fate of Proposition 8 (I am writing here not of the specific issues before the court, but of the general judicial presumption that should now apply). As much as it pains me to say this, given my own longstanding support of same-sex marriage, it would be inappropriate for the court in California to try to reverse the considered decision of the people of that State on the matter of their fundamental law.

Not only would it be inappropriate, it would not work. A judicial decision invalidating Proposition 8 would only be met by a judicial removal campaign or impeachment proceedings. Courts lack the power of coercion. The authority of any judicial branch rests on public acceptance of the legitimacy of its decisions. Once that sense of legitimacy is lost, it cannot easily be reconstituted, which is why, faced with the likelihood of public resistance to any other outcome, the acceptance of Proposition 8 by the California Supreme Court is almost inevitable.

At this point, supporters of same-sex marriage may feel an outraged sense of disappointment. How can it be, they may ask, that our fundamental rights are at the mercy of a passing majority?

Formulating the question in these terms—terms we have all heard in the media time and again—misunderstands what courts can do. The delineation and protection of fundamental rights is not necessarily the role of the courts. Our Constitutions—federal and state—are texts. They contain a number of rights that the courts do try to protect, but the documents identify what those fundamental rights are. Of course, the courts interpret this constitutional language, which is often both vague and broad, and in doing so sometimes announce “new” rights. But the process is not simple and direct, nor is it uncontroversial. The right to abortion, under the terms outlined in the Roe v. Wade decision, is an example of such a new fundamental right, and opposition to it has never disappeared.

The right to marry has certainly been called a fundamental right by the courts. But since this right has little or no textual grounding, traditional restrictions on marriage, such as kinship limits, have been routinely upheld. In other words, the fundamental right to marry, one might argue, only applies to marriage as traditionally understood.

The second ground for challenges to bans on same-sex marriage is some concept of equal treatment. A guarantee of Equal Protection is a textual right in most of our Constitutions, in fact, and it is true that the courts found anti-miscegenation statutes unconstitutional in the past on precisely that basis. Supporters have often compared bans on same-sex marriage to prohibitions on interracial marriage.

But again, the analogy from interracial marriage to same-sex marriage is not inescapably clear. It convinces me, but does it have the sort of obviousness that a judge can point to in the face of strong public opposition?

No Constitution, only a Constitutional People

If it is not to protect fundamental rights and ensure equal treatment, even in the face of majority opposition, then what is the role of the courts in our constitutional system? When the courts can rely on a fairly clear text, they have been pretty good at protecting our rights. Thus, the Supreme Court twice declared anti-flag-burning statutes unconstitutional as violations of the right of free speech. The courts also resisted Bush administration insistence that the War on Terror necessitated the abandonment of warrants for searches.

The courts are also pretty good at defending long-held conceptions of checks and balances. For example, the Supreme Court blocked the executive seizure of the steel industry during the Korean War and rejected a number of assertions of executive power during the Bush administration when given the chance.

However, the courts are reluctant to act where rights are not clear, and assertions of equality are not traditional. Even in these contexts, the courts have rendered decisions protecting novel rights and groups. But they have done so with an eye toward what the public will accept. In other words, judicial review ultimately depends on the ability of judges to gauge public opinion. When a decision properly judges the mood of the public, the decision is vindicated by eventual public ratification. The Brown case in 1954, though violently controversial at the time, had from the first a sense of rightness about it that caused even its opponents to avoid criticizing the decision’s moral center. The public criticism focused on states’ rights and was never put in terms of white supremacy.

This suggests that the judicial strategy employed by supporters of same-sex marriage may have been mistaken or at least premature. Although there have been successes, the ultimate scorecard has to acknowledge both that 30 states have enacted some kind of constitutional prohibition, and that Congress has reacted poorly to same-sex marriage proposals. In contrast, prior to the campaign for judicial recognition of same-sex marriage, legislative reform efforts were gaining ground in a number of states. Granted, these were usually modest civil union compromises, but they were not sparking the kind of backlash that led to the Proposition 8 effort in California. Such statutory reform could have laid the foundation for further legal development toward full recognition of the right to marry.

In retrospect, the federal courts were probably wise to avoid any suggestion of a federal constitutional right to same-sex marriage. A decision by the United States Supreme Court recognizing same-sex marriage would certainly have led to efforts to amend the Constitution so as to overturn that result, and it is by no means clear that such an effort could have been blocked. Even if a proposed amendment had been prevented, the result would have been renewed public support for right-wing politicians who would work with renewed vigor and public support to oppose same-sex marriage in a manner similar to the abortion restrictions on the books in many states.

It is not really true that we have a Constitution. That document, like the old Soviet Constitution, is just a piece of paper. What we have instead is a constitutional people. It is the commitment of the American people to the protections of the Constitution that has allowed our liberty to endure. That commitment has included majority respect for minority rights. Certainly there have been times when that commitment has faltered. At such times, as the treatment of Japanese-Americans and others during World War II shows, the courts are generally not much help.

But, as that shameful episode also shows, the people can return to their constitutional senses. The courts can help lead in that direction, but they cannot force.

The recognition of same-sex marriage seems to me inevitable because of its simple justice. Eventually, I believe, all the recent state constitutional prohibitions and federal statutory discriminations will be repealed, and judicial opinions will undoubtedly have a role to play in that development. But when that day comes, it will not be in the teeth of strong public opposition. Instead, it will come when many Americans, and maybe most, will be able to acknowledge (even if only grudgingly) the fairness that underlies the change.

This kind of alteration in public response is not unusual in our history. While public opposition to same-sex marriage remains strong today, there was a time that the public supported the criminalization of sexual relations among gay people. Yet, that sentiment faded. In 2003, when the Supreme Court finally declared such criminal statutes unconstitutional, there was very little public outcry. And now, merely five years later, there is almost no public support for that kind of statute anywhere in the United States.

That episode might be considered an example of the power of the courts. But it is not. It is instead an example of a constitutional democracy in action, in which the people accepted a judicial pronouncement of what justice requires.