The Blessed Virgin Mary could have appeared on the White House Lawn during Pope Francis’ US visit and no one would have noticed.

It was non-stop Francis across the media, social and traditional—not to mention huge disruptions of daily life in three major cities. While many are poped out, I highlight two major Catholic events that took place during the same week lest they pass, like the BVM might have, without our attention.

Gender Justice in Catholicism

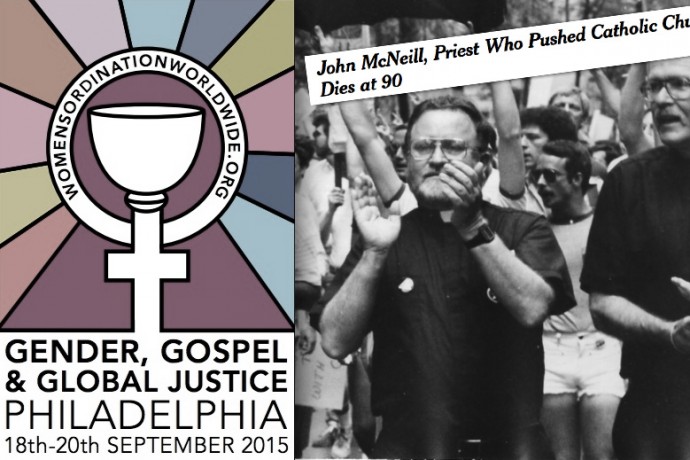

Five hundred people gathered from twenty countries in Philadelphia days before Francis’ visit to celebrate decades of struggle for feminist ministry and women’s equality in the Catholic Church. The 40th anniversary of the Women’s Ordination Conference provided a great occasion to lead the umbrella group, Women’s Ordination Worldwide, to assess progress and map strategies under the rubric of “Gender, Gospel, and Global Justice.”

The meeting began with Professor Shannen Dee Williams’ detailed presentation of shameful racism in women’s religious congregations. Black lives simply did not matter for decades in those circles, just as in most of the church. Her eagerly expected book on which the presentation was based is a potent reminder of the anti-racism work that must now be an integral part of progressive Catholicism.

Full disclosure: I myself lectured on the achievements of the movement, especially our success in avoiding being coopted by a kyriarchal church. Ordination is a stated goal that some Catholic women have reached by taking the ordination process into their own hands, as with Roman Catholic Womenpriests and the Association of Roman Catholic Women Priests. The movement’s major achievements include creating many forms of feminist ministry and theology—as theologian Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza explained—replacing parishes with base communities, developing inclusive language and imagery, and building respectful egalitarian relationships among ourselves.

There is abundant reason to celebrate and so we did.

A highlight of the event was Mercy Sister Theresa Kane’s presentation and the awards given in her name. Theresa is widely revered for her 1979 graceful speech to Francis’ predecessor Pope John Paul II. She famously welcomed him to the U.S. by calling for women’s full participation in the ministry of the church (otherwise known as ordination). He was appalled, an emotion that set off a Vatican chain reaction of anti-women, (including anti-nun) activities that persist to the present. At this WOC/WOW event, Theresa reiterated and elaborated on her position in an open letter to Francis. Alas, thirty-six years later, while her words were cheered in Philadelphia, the letter fell on closed minds in Rome.

Another conference high point was a panel entitled “Equal in Faith” chaired deftly by Interfaith Voices host Maureen Fielder. Jewish, Mormon, Muslim, Anglican, and Catholic women made clear that religious sexism is practiced in many settings. But it was equally clear that once progress is made (as with Reconstructionist Judaism, for example) the whole community gains.

Scholars and activists from around the world offered insights into ministry, deacons, transgender people, archeological finds, and so much more, all pointing to the obvious need for gender justice in Catholicism. Indian women described how they collaborate with local bishops. Survivors of clergy sexual abuse told their stories and reported on their tireless work to eradicate violence, a sharp contrast with the pope’s milquetoast comfort to bishops.

Several male former priests and one still active in ministry (who was relieved later of his pastoral duties) explained the price they have paid for their support for women’s ordination. Their solidarity was more than welcome. Their loss of privilege, while painful, pales in light of countless women’s exclusion from ever exercising ordained ministry. (Not surprisingly, the four men received far more secular press attention than the conference itself.)

Woven throughout the meeting were prayer services and liturgies, including a shared Eucharist, that demonstrated the advances Catholic women are making in creating new, inclusive forms of faith that make sense in postmodernity. There was no rote repetition of the rubrics of the Mass. Instead, the planners offered creative, imaginative, and uplifting experiences of worship that would benefit the whole church if only…

There wasn’t a vestment in sight that weekend in Philadelphia. Deo gratias.

We danced, sometimes the best thing for body and soul in the face of overwhelming odds. As the papal visit unfolded, it was clear that there was no competing with the power of the Vatican on the uneven turf we occupy. Nonetheless, five hundred people went home energized from Philadelphia confident that the struggle for Catholic women’s equality has just begun.

John J. McNeill, Death of a Queer Catholic Elder

Another signal Catholic event of the week eclipsed by the papal visit was the death of John J. McNeill. John was a former Jesuit priest, an openly gay man, a scholar, teacher, therapist, and prophetic leader who died on September 22, 2015, at the age of ninety, during the visit of the first Jesuit pope to Washington, D.C.

In a perfect (ok, even a decent) world, Pope Francis would have announced John’s death the next morning. He would have hailed his brother Jesuit as the pioneer honest gay man that he was, lauded his massive pastoral contribution, and recommended his marvelous books for widespread study. He would have lifted John’s name in praise, paid his condolences to John’s husband, Charles Chiarelli, and expressed his sympathy to the thousands of members of DignityUSA of which John was a longtime collaborator, to interfaith groups where John was beloved, and to the Sunshine Cathedral Metropolitan Community Church in Florida where John and Charles worshipped.

In my dreams.

Alas, not even in the blog attached to the Jesuit magazine America has there been a peep about one of their own. Perhaps such Jesuit matters are handled behind closed closet doors, but that is precisely the problem. John McNeill paid a steep price for coming out early and often. I will be long dead, but I fully expect John to be proposed for sainthood like Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker Movement, whom Francis cited in his “Sermon on the Hill” at the Capitol. She famously implored, “Don’t call me a saint. I don’t want to be dismissed so easily.” John would have said the same thing. In time, he will probably suffer the same fate as Dorothy whose candidacy for sainthood is being advanced by well-intentioned supporters. My Catholic high school in Syracuse, New York was forbidden by the diocese to host her in the late 1960s. Being domesticated in death by a church that fails to appreciate one in life is distasteful.

Attention to John McNeill and his ministry is a powerful antidote to much of the holy hoopla of the papal visit. Brendan Fay captured the contours of John’s life in a fine film, “Taking a Chance on God.” John found his priestly vocation as a prisoner of war in Germany when a Polish man tossed him something to eat while making the sign of the cross. John joined the Jesuits, engaged in study and formation, doing it all right until he fell in love. The rest is an important chapter in church history.

Starting with his hallmark book, The Church and the Homosexual (1976), John was a public advocate in print and on the airwaves for opening discussion. He urged new ways of thinking religiously about same-sex love, inspiring not only Catholics, but also colleagues of other faiths to bring the same critical view to their scriptures and practices to find queer-friendly ways to be religious. He always encouraged people to practice their faith insofar as their conscience allowed. For this, the institutional church scandalously silenced him. He accepted their sanctions for years until he could not longer reconcile his conscience with the cowardice of ecclesial officials.

People were dying of AIDS and the Vatican, under the pen of Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, was prattling on about the “intrinsic moral evil” of homosexual orientation. John had enough guts and good sense to stop colluding with such nonsense and got on with the ministry to which he was committed. The Society of Jesus eventually dismissed him. Many friends like myself noticed that while they may have taken the man out of the Jesuits, they never took the Jesuit out of the man. He maintained a deep faith and a critical consciousness to the end of his distinguished life.

Making a living and preparing for retirement was not something the Jesuits worried about for John after he left the community. It is hard to start over in midlife, but John became a much-in-demand therapist in New York City. He counseled hundreds of LGBTIQ Catholics, many of whose problems were tied directly to the Roman Catholic Church’s theology that he tried so valiantly to change. He wrote several more important books, including Taking a Chance on God (1998), a title that aptly sums up his life.

John McNeill’s ministry was legendary. For decades, he collaborated with evangelical feminist scholar Virginia Ramey Mollenkott in yearly conferences that drew hundreds of people to Kirkridge, a progressive retreat center in Pennsylvania, for sustenance and challenge. The two functioned as the beloved elders that so many queer people simply never had. He was an expert on Maurice Blondel and she on John Milton so their lectures and conversations were intellectually rich as well as deeply pastoral.

John was a Catholic’s Catholic. He was an Irishman from Upstate New York where he joined the likes of University of Notre Dame President Theodore Hesburgh and brothers Daniel and Philip Berrigan in peace and justice activism before it was fashionable elsewhere. He had a sister who was a nun in an order that might not have prayed for LGBTIQ Catholics except that he asked her to do so, and so the sisters did.

John and I sparred publicly at Kirkridge about whether in all eternity we would be compost (my view) or live on in individual mortality as he insisted. We agreed to disagree, hoping that neither one of us would find out any time soon. The fun part of theology is being able to disagree vigorously and still join around the table together as friends. I’m happy to say we were.

Both the women’s ordination struggle and the death of John McNeill during the octave of Pope Francis’ visit to the U.S. have enduring significance in religious history. Long after the smell of incense and the papal posters are gone from Washington, New York, and Philadelphia, Catholic women will achieve equal rights and LGBTIQ Catholics will enjoy the respect John McNeill earned—or die trying.