What does it mean that a quarter of all Americans “describe their religion as ‘nothing in particular‘”?

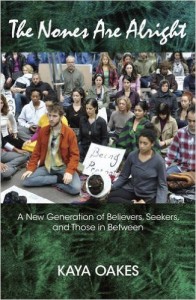

In her newest book, The Nones Are Alright: A New Generation of Seekers, Believers and Those in Between, Kaya Oakes ventures deep into the territory of the so-called “nones,” the ever-growing segment of the population that refuses religious affiliation.

But as Oakes relates, in a series of compelling narrative accounts drawn from interviews, those who have left institutional religion are not the godless horde we might imagine—instead many of these, millennials especially, “live in a space of permanent questioning.”

The Nones Are Alright: A New Generation of Believers, Seekers and Those In Between

Kaya Oakes

Orbis Books

(October 2015)

In this special roundtable, Peter Laarman leads a conversation with Oakes, along with Richard Flory, the director of research at the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at University of Southern California, and Sikivu Hutchinson, atheist scholar and author.

_______________

Peter Laarman: Kaya and those whom she interviews cite a range of aspects of traditional religious life that clearly repel younger people and help fuel the unaffiliated phenomenon.

On the one hand, they all cite what we might call a set of interrelated “definitional” problems: hierarchy, patriarchy, dogma, and homophobia. On the other hand, they almost all cite the huge “experiential” problem of worship services that are insipid and lifeless, along with a social justice witness that is equally insipid.

Can either of these push-out factors be “fixed” without also fixing the other? What is your own reading of the relative importance of the different repellents?

Kaya Oakes: I would argue that these things have to be “fixed” on a continuum. Even the most beautiful liturgy is going to be hollow without a central message that is life-giving and inspiring. And even the most enlightened and progressive message at the heart of that liturgy is going to be lost if it doesn’t also get enacted outside of the walls of an institutional religion.

I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the social movements that have most lit a fire of passionate participation in the last few years have been leaderless. Occupy and Black Lives Matter both exist because people made them happen out of a sense of urgency. Institutions move slowly in comparison, but if any religious tradition were able to pick up on some of the energy and prophetic sensibility in those many-voiced choruses, it might actually be compelling. Can this happen in a loop? Change on the outside/change on the inside. Perhaps that very dichotomy of outside/inside is the problem.

Richard Flory: I think that Kaya’s response to this question is right, but I want to refocus it in a slightly different way (i.e. more sociological—sorry about that!). I totally agree with her assessment of why individuals leave their religious homes, but the broader issue is related to larger processes in society, namely the crisis of authority and why anybody should listen to people in authority, or belong to any group that tries to make authoritative claims for individuals, communities and societies. People just don’t trust authority or large-scale institutions in the same way they did 30 or 40 years ago.

“In the absence of truly democratic policies that provide equitable access to jobs, housing and education, the social and cultural institutions provided by some black churches, both alternative and traditional, represent an antidote to these inequities.”

The causes are likely many, including political corruption (Nixon most publicly), technology (everyone is an expert now, and if I don’t know something I can look it up on my phone), globalization (multiple claims to the same authority coming from incredibly diverse sources), and corporate corruption (you win if you cheat, the little guy gets screwed). This translates into religious and spiritual authority as well, what with sex scandals, health and wealth theologies, and various corrupt religious leaders all demonstrating why we shouldn’t take their religious claims with any sense of authoritative validity.This, coupled with the American cultural values of individual choice in all things, leads to a general dissatisfaction with the available options for religious/spiritual seekers.

So if you take Kaya’s explanations and combine them with my claims, you have a situation where religious organizations—particularly older forms—are operating in a world that increasing numbers of people are not interested in, and are simply irrelevant to their lives.

So in response to Peter’s question about how to “fix” the issues pushing people out of religious institutions, they are of a piece—what is the world that people are really living in, and in what ways do establishments (i.e. churches, synagogues, temples, etc.) actually address these issues, and to what extent do they provide a transcendent experience that is relevant to the life experiences of adherents (both current and potential).

PL: Also I was struck by the passage in the middle of the book about the crisis of belief itself. Kaya, you write about acedia and quote St. John Cassian on the “noonday demon” of an inability to connect spiritually. I want to ask, for you yourself and for the people you interviewed, whether the crisis of belief issue is mainly disbelief or doubt regarding God’s existence, or is it more a matter of distance—of believing but still not being able to feel the divine presence, partly because of the speed and fragmentation experienced in contemporary culture? It seems to me that although both play a role, the difference between disbelief and distance is important. Parse this for us, please.

Kaya Oakes: I’ve been hearing a lot lately about “dry prayer,” both from Catholic and Protestant friends, clergy and laity alike. Cassian was talking about that in the context of monasticism, but in our cultural context where we don’t have time for anything—including reading books, really—perhaps that distance you’re referring to is a matter of an inability to focus on a relationship with the divine. So if a person does believe, perhaps what’s occurring, which they refer to as doubt, is really a lack of time and focus.

On the other hand, the fact that so much scientific evidence exists that denies or complicates the question of God’s existence means that doubt, added to distance, often comes into play. Couple this with the generational loss of interest in religion and you can see why Nones are actually becoming more and more secular and moving away from even that loose relationship with a higher power.

So distance comes first, then doubt. Then denial, if you like alliteration as much as I do.

PL: Sikivu, for some years now I’ve heard black church leaders speak despairingly of the “post-soul generation” without being able to offer any kind of alternative way of doing church or being church for younger African Americans. Is it your impression that black millennials, and young activists in particular, are doing their own version of DIY church or are they drawing their spiritual nourishment in ways that have nothing to do with church in any form? There’s certainly a historical precedent for young justice activists finding it impossible to remain inside quiescent religious institutions.

Sikivu Hutchinson: There’s conflicting data on this for African-American millennials. First, there was an interesting article that came out last year which indicated that African-American millennials believe the black church is increasingly obsolete. This piece identified the black church as being “out of step on scientific developments” and charged that some black millennials “feel Christianity leaves no room for authenticity.” Certainly the scandal and hypocrisy-plagued version of the black church that younger generations see reflected in their communities, as well as in the media, has led younger generations to rethink religion.

However, according to the Pew Research Center’s 2007 and 2012 reports, black millennials ages 18-29 comprise 20% of historically black churches. This number is roughly comparable to that of the baby boomer generation. Thus, religious affiliation for young black adults does not show the same kind of downward shift as that of the non-black population (the data on black children in the generation after the millennials suggest high levels of religiosity as well). African Americans in general, and African-American women in particular, are among the most religious groups in the nation. So, even though black youth may be expressing their dissatisfaction with the orthodoxies and dysfunction of the black church, they are not, by and large, abandoning these traditions wholesale. This has a lot to do with the role the black church—for good or for ill—continues to play in segregated African-American communities vis-à-vis social welfare, cultural cohesion, political engagement and educational opportunity (i.e., providing scholarships, linking with colleges and universities, establishing safe spaces for studying/tutoring/mentoring, etc.).

African Americans in general, and African-American women in particular, are among the most religious groups in the nation. So, even though black youth may be expressing their dissatisfaction with the orthodoxies and dysfunction of the black church, they are not, by and large, abandoning these traditions wholesale. This has a lot to do with the role the black church—for good or for ill—continues to play in segregated African-American communities vis-à-vis social welfare, cultural cohesion, political engagement and educational opportunity (i.e., providing scholarships, linking with colleges and universities, establishing safe spaces for studying/tutoring/mentoring, etc.).

It’s important to remember that African Americans (along with Latinos) continue to be the most residentially segregated in the U.S., have the highest unemployment rates and suffer the largest wealth disparities in the country. Black youth continue to be mass incarcerated and pipelined into prisons in disproportionate numbers, while being marginalized in mainstream public school curricula.

In the absence of truly democratic policies that provide equitable access to jobs, housing and education, the social and cultural institutions provided by some black churches, both alternative and traditional, represent an antidote to these inequities. Hence, while remaining largely spiritual-to-religious, younger African-Americans do experiment with alternative faith traditions: the Agape church, Unity Fellowship Church (founded by HIV activist Reverend Carl Bean), and other LGBTQ congregations that have been started by queer African-American folk come to mind.

PL: Dick, you’ve looked at the “nones” through the eyes of a trained sociologist, and you have a particular interest in tracking younger evangelicals. What are the distinctive drivers affecting the younger evangelicals who end up unaffiliated? Is it the case that the issues for evangelicals are not so much belief-related as they are culture-related—i.e., young evangelicals finding themselves culturally at odds with their church over what they regard as cramped social views?

Richard Flory: First I think we need to differentiate between those within the “nones” who are unaffiliated with any religious institution but still believe in something, and those who are either “unbelievers” or uninterested in the whole issue of religion, but may maintain some form(s) of belief, however vague that may be. Most of the people that Kaya writes about are those who do not fall in the latter two categories, but instead are on some form of a spiritual or religious quest. They actually believe that something “out there” exists, which they also believe (or hope) will help them find a purpose in their lives.

“I think this is the larger issue that many younger evangelicals are reacting to and against. They aren’t disinterested in Jesus or being a Christian, but they are completely disinterested in the corporate packaging and boundary patrolling that the evangelical industrial complex produces.”

This would all be true of evangelicals as well. There are many who have just left religion and have no interest in returning or pursuing a spiritual/religious quest. Most, I would think, for many of the same reasons that we hear in Kaya’s book. Others are still interested in being Christian, but are completely disinterested in being evangelical. This manifests itself in a small percentage heading for Mainline Protestant or Catholic churches, but most are either sticking it out or forming other kinds of churches and communities that have a different focus than the churches they grew up in.

I think you’re right Peter, that for this group of evangelicals (mostly younger, but not exclusively so), the issue is less belief per se than their dissatisfaction with the existing church forms that dominate evangelicalism. And, this is related to issues like their greater acceptance of LGBT rights—even if they still may have some questions about that theologically—social issues and politics.

I’ve talked elsewhere about the “evangelical industrial complex,” which includes not only churches but colleges, universities and seminaries, elementary and high schools, publishing houses and other media corporations, authors, speaking tours, conferences, and the like, that really sets evangelical orthodoxy, both theological and cultural. I think this is the larger issue that many younger evangelicals are reacting to and against. They aren’t disinterested in Jesus or being a Christian, but they are completely disinterested in the corporate packaging and boundary patrolling that the evangelical industrial complex produces.

PL: At several points in the book, Kaya alludes to the role played by the culture of distraction in complicating or even in suppressing spiritual life. We all know there’s really no turning back of the technological tide. This contextual element seems hugely important. Your thoughts on this point?

“Capitalism has colonized every part of our lives such that the requirements of ‘making it’ in a hyper-capitalist society like the U.S. (and increasingly globally) is at odds with any sort of religious or spiritual life.”

Kaya Oakes: The question remains how the distractions can be channeled into something spiritually productive. I’m a big fan of Twitter as a place to make connections with other people who are thinking about questions of religion, but it slides into harassment and trolling so easily that productive discussions never last long. And that’s ultimately the problem: how can technology become something about listening?

Plenty of ministers are scrambling to get their congregations on social media: is it making a difference? I have no idea—the church I attend lately has its own app, but that’s not why I picked that church. I picked it because the pastor actually started a conversation with me the first time I attended, and because it has a social justice message that it actually lives out in the local community through action. So technology might be a great set of tools, but it cannot replace encounter, and many churches are just terrible at that.

Richard Flory: I would broaden the point from the distraction caused by all of the technology we carry in our pockets, to how capitalism has colonized every part of our lives such that the requirements of “making it” in a hyper-capitalist society like the U.S. (and increasingly globally) is at odds with any sort of religious or spiritual life.

For example, on a practical level, in my interviews with younger people, many will say that they want to attend religious services more regularly, but they work when services are offered. On a more theoretical/theological level, capitalism tells us to maximize our own individual (or corporate) profit without regard to the consequences for others. This seems to go against what most religious traditions teach.

PL: It was striking to see how many of Kaya’s interview subjects are already actively engaged in resistance movements of one kind or another. Even the ones doing direct service work seemed to put a social critique behind it. With the exception of a small elite in this winner-take-all economy, the bulk of American millennials will face significantly lower lifetime incomes than their parents’ generation enjoyed. The digital devices that in some ways liberate them are also used by their bosses to further commodify and degrade them: to minutely control their work lives, even spy on their personal lives.

Against this backdrop, to what degree do you feel that the new formations of folks exiting traditional religion but still feeling some kind of “God-shaped space” will create a new spiritual culture in which resistance to exploitation and degradation is a central theme?

I realize it can be argued that strong and growing resistance movements, notably Black Lives Matter, already constitute the new spiritual formations needed by the exiles, that there is no need to add any more spirituality than is already inherent in the community of struggle.

Kaya Oakes: This occurred across the people I spoke with, and I too found it interesting. There’s some evidence that Nones tend to lean politically to the left, which may explain the idea that they’re interested in justice issues even while being less interested in how religion might serve those justice issues. And your example of the deep spirituality of Black Lives Matter is a good one. Think of Bree Newsome pulling down the Confederate flag while praying a Psalm. Action + spirituality + tradition, but in a radically different context/action than an organized march or voter drive or the like.

Friends who were involved in Occupy say the same about the deeply spiritual experience of being together in the camps. I think this kind of resistance is a huge, growing thing among younger Americans. Right now, Yale and Missouri are two examples. Perhaps the new spiritual culture is the eruption of a generation coming into its social consciousness and wanting to enact that. And if some of those people were raised with only vague ideas about religion (many Nones had None-ish parents), they might not realize all of the ways in which that resistance to injustice is in many ways deeply spiritual. Perhaps that will come later? Or perhaps we are already seeing it unfold.

Sikivu Hutchinson: I find that framing these movements in “spiritual” terms is problematic because that terminology marginalizes secular folk of color who are also present in and contributing to the movement. I think characterizing #SayHerName as a “spiritual formation” also minimizes the intersectional coalition-building that has gone into making black women’s lives and bodies visible within the broader sphere of traditional mainstream civil rights discourse and public policy.

PL: Throughout the book and especially toward the end, Kaya expresses relatively little anxiety about the death of “religion” as we have known it. She holds open the possibility of a resurrection we can’t currently imagine.

I’m older than the rest of you, but I’ve gotta say that I do get kind of emotional about the collapse of the old edifice, mainly because I don’t want young people to miss out on the good stuff that the old structure could sometimes deliver: the heart-stopping magnificence of a well-done traditional service, the kneeling at the altar with hundreds of others to receive the eucharist, the mighty cloud of witnesses vibe, all of that.

Experiences like these are more than merely aesthetic to someone like me; they are also formative. So I guess I am just a bit anxious about where we’re heading. What about the rest of you?

Richard Flory: Institutions and organizations have to adapt and change or run the risk of going out of business. Religious organizations are no different.

If a particular organizational form or experience isn’t adapted over time so that it makes sense in the current social and cultural context, that group will ultimately fail. But I don’t think that necessarily means throwing everything out—adaptation is adjustment to challenges and demands from members (and potential members).

And I would say that even mainline Protestants, despite the fact that they seem like they’ve never changed, have done just that. They became a separate entity from what came to be known as “fundamentalists” in the early 20th century by adapting their theology to current ways of thinking about science. This has continued over the years with changes/adaptations around gender, LGBT, social justice, etc. Maybe it’s time to start adapting forms of liturgy (which in reality has probably already happened).

But I don’t think that will save older forms of religion. More likely, at least in the U.S., the forces of individualism, choice, a more democratized understanding of authority, broad access to all forms of knowledge (religious and otherwise), and the like, will continue to require religious organizations to adapt and change in response to new ways of thinking and “being” that results from how these cultural patterns develop.

Kaya Oakes: I happened to attend church recently with two friends who are Catholic Sisters. One is 83 and the other 90. And most of our conversation afterwards was about how much freer they are now, how they can live out their faith differently, how they lived through decades of nasty superiors and terrible bishops and liturgy in a language they didn’t really understand. It made me think about what I missed, generationally, and what’s being lost.

You’re right that there is something sad about the passing of the old edifice, but will it ever really entirely go away? My friend, whom I write about in the book, who’s a former “none” turned Benedictine monk might be the only member of his novice class, but as long as there are enough people attracted to that life and they can afford to keep the lights on, the lights will stay on.

And the art, literature and architecture that came out of times when religion dominated people’s lives is not going to go away. If we can have the freedom my Sister friends were talking about coupled with the beauty, what might that mean? That the edifice will survive but the internal workings will look very different.