Last week, Roy S. Moore, chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, ruled that his state’s probate judges must enforce Alabama’s ban on same-sex marriage.

Moore, who first rose to national fame for his crusade to publicly display a mammoth Ten Commandments memorial, is fighting a losing battle. The Supreme Court ruling from Summer 2015 is the law of the land. But Moore’s act, like the giant stone monument he championed, has symbolic heft. It is a little like the House of Representatives’ repeated, quixotic attempts to repeal Obamacare—a lost cause, perhaps, but one the resonates profoundly with the conservative faithful in Alabama and around the country.

Call it righteous defiance.

Right-wing Christians point to another Alabaman, Rosa Parks, as the model for Kim Davis, the Kentucky County Clerk who also refused to budge. They see the fight against an encroaching federal government and the crusade to safeguard “traditional marriage” as a sacred calling. Indeed, evangelical pastor Rick Warren has said the campaign is the civil rights issue of this generation.

Others in the conservative camp spent a great deal of time and energy saying as much in 2015. For instance, on June 10, 2015, a group of dozens of religious and social conservatives published a full-page open letter to the Supreme Court in the Washington Post. The statement, upholding what signers called the “biblical understanding of marriage,” received the endorsement of high-profile figures, many who had focused their careers and ministry on defending what they called “family values.” These included Franklin Graham, James Dobson, John Hagee, Tom Delay, Rick Santorum, Jim Garlow and Alan Keyes. The open letter proclaimed:

We affirm that marriage, as existing solely between one man and one woman, precedes civil government. Though affirmed, fulfilled and elevated by faith, the truth that marriage can exist only between one man and one woman is not based solely on religion but on the Natural Law, written on the human heart. . . . We implore this court to not step outside of its legitimate authority and unleash religious persecution and discrimination against people of faith.

Its peroration summoned the faithful: it was “an unjust law, as Martin Luther King Jr. described such laws in his letter from the Birmingham jail.” It must, of course, be noted that for King to be acceptable in such circles he has had to be scrubbed of his liberal Protestantism, his anti-war stance, and his ideas of social justice and communalism. His legacy redacted King has now entered the religious right pantheon.

I would argue that the Washington Post letter fits a historical pattern, but one that is far removed from MLK and the modern civil rights movement. It is part of what some historians have rightly named the “long southern history of infringing on some people’s rights in the name of other people’s liberty.”

Conservative politicians and activists have led a virtual parade of victimhood. Richard Nixon, who could nurse a grudge as few others could, may have been the most adept of the lot, but others picked up where he left off. Presidential candidates Barry Goldwater in 1964, George Wallace in 1968, and Ronald Reagan in 1980 implored and sometimes convinced voters that white, straight Americans were being threatened by an array of enemies.

That sense of being beleaguered and embattled has been basic to many modern white southern notions of religious liberty.

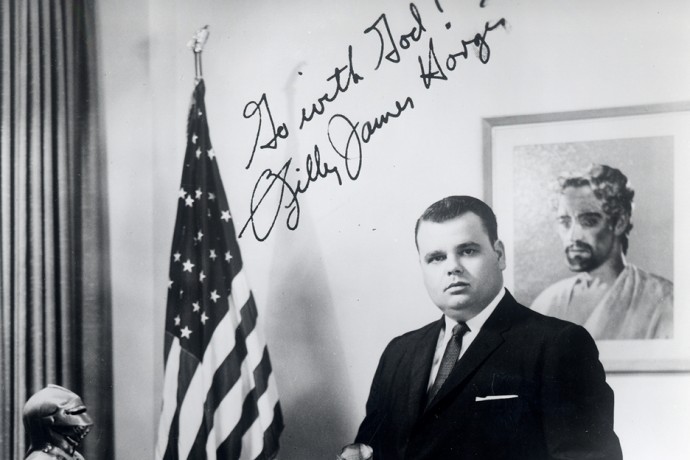

A little over 50 years ago few embodied this position as well as the Tulsa-based head of the Christian Crusade, Billy James Hargis. Fellow Sooners called the anti-communist stalwart a “bawl-and-jump” evangelist. It is not MLK, but Hargis—with his Strangelovian militarism, opposition to civil rights and government intervention on the part of minorities—who is a more fitting precursor to the modern “religious liberty” movement.

Hargis’s Christian Crusade organization might well have been the best-funded, far right organization in the country in 1963-64. The tax exempt, nonprofit group drew in roughly $1 million in contributions in 1963 alone.* The Tulsa leader’s radio broadcasts ran on over 100 stations and he branched out into television as well.

Hargis fine-tuned the notion that conservatives, and especially white southerners, were being wronged by a tyrannical, vocal minority, while also having their own rights curtailed by an activist, liberal government. He shared some of his ideas and tactics with other far-right fundamentalists in these years, like Carl McIntire, Bob Jones and Bob Jones, Jr., and John Rice. For these and others like them, their country and what the thought it stood for, seemed to be slipping away from them.

Looking back on the turbulent 1960s from the vantage of 1980, Yale University historian of American religion Sydney Ahlstrom considered the revolutionary developments in religion and ethics. “Never before in the country’s history,” he recalled, had “so many Americans expressed revolutionary intentions and actively participated in efforts to alter the shape of American civilization in almost every imaginable aspect—from diet to diplomacy from art to the economic disorder.”

Hargis was painfully aware of those changes to the country’s moral landscape in this turbulent decade. From the pages of his organization’s magazine he targeted liberal ecumenical Protestants, the SCLC, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, and more.

College campuses would remain a kind of battleground for Hargis and like-minded fundamentalists—the forces of liberty did battle with “tyranny” for the souls of youth. Left-leaning folk music, the soundtrack of young civil rights activists, was particularly to blame for anarchy and dissent: “Satan is concentrating full-time on America’s youth,” warned Hargis in early 1967. The hawkish evangelist singled out popular university performers like Pete Seeger. “Two of the most popular folk songs on college campuses today across the land are ‘Draft Dodger Rag’ and ‘I Ain’t Marching Anymore,’ written by another pro-Red, Phil Ochs,” he thundered. It all rang of treason, or something even worse.

For Hargis and members of the Christian Crusade all criticism of the organization’s tactics or its confrontational ideology amounted to severe persecution. A journalist in the Saturday Evening Post observed of Hargis: “any comment short of adulation is considered a smear . . .”

Today’s conservative evangelicals see any straying from what they consider God’s plan for America as a kind of national apostasy—the liberty of Bible believers was and is under threat. In this fear they bear the imprint of Hargis and his contemporaries.

In January of 1963, for example, the Christian Crusade organized an anti-Communist rally in Boston. With vocal opposition in the region, it did not go as the Tulsa minister had hoped. In Hargis’s inflated sense of outrage, he saw the NAACP, the AFL-CIO, CORE and the press joining forces to curtail the anticommunists’ freedom of expression. “Christian Crusade can expect all the big guns of liberalism to be aimed at this highly effective movement throughout the year,” he prophesied, “as they desperately attempt to destroy Christian Crusade and repudiate its founder and director.” Immediately after the rally, Hargis told Boston’s CBS Radio affiliate that there was more political and religious freedom in Oxford, Mississippi, than there was in Boston.

A similar discourse of embattlement and doom predominates today. Christian psychologist and childcare expert James Dobson recently warned: “barring a miracle, the family that has existed since antiquity will likely crumble, presaging the fall of Western civilization itself.” In apocalyptic tones reminiscent of fundamentalists in the 1960s, Dobson asserts: “Pastors may have to officiate at same-sex marriages, and they could be prohibited from preaching certain passages of Scripture.”

Fifty years earlier Hargis felt similarly under siege. “If all our friends only knew the satanic pressures that are exerted against us daily . . . trying to stop this activity,” he told his constituents, “trying to discourage and frighten the workers,” then supporters would be far more generous with their donations.

The language of victimization convinced those who were fighting under the conservative banner that they were the true champions of liberty. Other causes paled by comparison. In 1960 Hargis mocked the “social crises” of racism and segregation. It was “one of the most artificial of all such crises, instigated by Communists within America to add racial hatred to class hatred, and thus betray America into communist hands through the betrayal of the American Negro.”** Several years later, as the black freedom struggle grew in strength and momentum, he would tell a reporter, “The persecuted minority in America is not the Negro, but the white folks of the South.”

Claiming to not be racist or homophobic, religious right leaders have resorted to the basest language in the same breath. Take, for instance, Hargis’s appeal in a section of one of his books on “Plain Talk to American Negroes”:

Granted that the Negroes were first brought here as slaves. You can’t blame the whites of today for that. In fact, slavery may have been a blessing in disguise if it meant introduce the feuding black tribes of Africa to Western civilization. Here in the United States, thanks to education, personal hygiene, and Christian culture, the Negro has advanced to a greater degree of progress than anywhere in the world.

Here is Dobson, similarly obtuse (to put it kindly), in the weeks before the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling on same-sex marriage:

For more than 50 years, the homosexual activist movement has sought to implement a master plan that has had as its centerpiece the destruction or redesign of the family. Many of these objectives have largely been realized, including widespread support of the gay lifestyle… overturning laws prohibiting pedophilia, indoctrinating children and future generations through public education.

How to explain this sense of embattlement, this idea, particularly pervasive in the American South, that personal or religious liberty is under fire?

Recent scholarship in Southern studies is of some help here. Angie Maxwell has observed, for example, that the “southern lexicon has long been rich in” the language of regional inferiority. In her view a “climate of battle” and perceived “public ridicule have significant ramifications for southern white identity.” It began, she contends, in relation to a “black ‘other.’” It would develop into “a comprehensive cosmology defined in opposition to a mounting pantheon of enemies old and new.”

Finally, moving to a national context, historian Rick Perlstein has noted that such defensiveness has unified much of conservatism from the days of Barry Goldwater and Ronald Reagan to the present. “Conservative culture was shaped in another era,” Perlstein remarks, “one in which conservatives felt marginal and beleaguered. It enunciated a heady sense of defiance. In a world in which patriotic Americans were hemmed in on every side by an all-encroaching liberal hegemony, raw sex in the classrooms, and totalitarian enemies of the United States beating down our very borders.”

And yet, as we’ve seen, that era may not be so distant from our own.

_______________

[See here for the program of the conference at which a version of this article was originally presented. –Eds.]

NOTES:

* Billy James Hargis, “Operation: Campus Awakening,” Christian Crusade fundraising letter, February 15, 1967. Spencer Library, University of Kansas, Wilcox Collection.

**Billy James Hargis, Communist America . . . Must It Be? (Tulsa, OK: Christian Crusade, 1960), 97. See also issues of the Christian Crusade magazine from the early 1960s, and Hargis, Facts about Communism and Our Churches (Tulsa, OK: Christian Crusade, 1962). Jeff Woods, Black Struggle, Red Scare: Segregation and Anti-communism in the South, 1948-1968 (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2004), 119, 191.