Three years ago during the Lenten season, I wrote a piece for The Revealer called “Watching Jesus Films for Lent.” Therein I discussed the curiosity of the way cable television stations, from the History Channel to Turner Classics, broadcast fictional and scientific accounts of Jesus during Lent, and the ways in which we modern television viewers begin to see a plurality of Jesuses. Since then I’ve watched a lot more films, and am strangely happy to say that Jesus, elusive as he is, is alive and well in cinemas around the world. But there is a caveat: these Jesuses are not the ones most English speakers grew up with, nor are they the historical Jesuses of the History Channel. It’s not just the lack of a blue-eyed, Jeffrey Hunter-Jesus in King of Kings in these international accounts, but a wholly other way of seeing that dominates many Jesus films around the world.

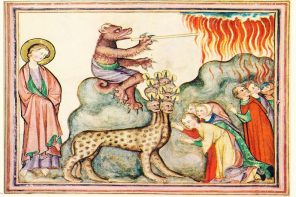

Films produced in the United States such as Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ or Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ have revived ancient conflicts over the dual-nature of the Incarnation. The Scorsese account, from Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel, was all too human, while Gibson’s account, channeled through medieval Catholic piety and the anti-Semitic hallucinatory visions of Anne Catherine Emmerich, provided a sort of “superhero” dimension to Jesus. Divine or human, superhero or just sacrificial beast, the Jesus story provides a wealth of takes for visual artists, gospel-writers, and filmmakers. Meanwhile, one other dual-natured conflict of filmed Christ figures could be imagined on film, and that would be to contrast an American Jesus with an International Jesus. Kind of a New American Standard Bible translation in comparison with a New International Version; the stories are similar but told from differing perspectives.

I am here imagining some future Lenten season when we can cue up a series of Jesus films made outside of the United States, and by so doing realize the plurality of Jesuses—the ways Jesus might be seen outside the Hollywood-dominant framework. I here offer four takes on Jesus films; an updated gospel for the film age, a gospel account that takes into account the various takes on Jesus as prophet and priest, but also as liar, lunatic and/or lord.

Indian Blockbuster Jesus

Opening our new testament of filmic gospels is the Telugu production Karunamayudu (“Man of Compassion,” directed by A. Bhimsingh, 1978), which has been seen by over 100 million viewers, a number rivaling many a blockbusting Hollywood film. For the past three decades in South India and beyond, villagers have gathered in front of makeshift outdoor theaters to watch the life of Jesus onscreen. A devout Christian production, yet it is over two and a half hours long and incorporates a South Indian cast. The film style resembles Hindu devotionals more than a Western-style Jesus film, and within a broader view of Indian film, Jesus becomes part of the pantheon of deities. Dwight Friesen, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, is finishing his thesis on the film and its afterlives, and discusses it as “a fascinating blend of the Western biblical epic and elements of the Indian historical, devotional, and mythological genres.” Karunamayudu even filmically achieves the noted Indian mode of mutual sacred gazing, understood through the term darshan. In other words, this Jesus utilizes a local visual vocabulary to make himself known.

Questioning the Sanity of the Saviour

From another tack altogether is Man Facing Southeast (1986), written and directed by Argentine filmmaker Eliseo Subiela, whose later “religious” films include Don’t Die Without Telling Me Where you are Going (1995) and Adventures of God (2000). Man Facing Southeast is a film with obvious Christic references, full of seeming miracles and a lighting schema that emphasizes the sacrality of the main character, but simultaneously questions the sanity of the savior: the film is set in a mental institution and the “man” who faces Southeast (Rantes) is one of the patients. (The film was blatantly plagiarized by the novelist Gene Brewer and made into the film K-Pax in the United States.) Rantes is somewhere betwixt and between a messiah, an insane person, or an extraterrestrial, and the film does not tie up any of the loose ends. Whether or not Subiela had the C.S. Lewis trilemma in mind (“Liar, Lunatic, or Lord”) is not clear, but the film fleshes it all out in rousing ways.

The Last Jewish Prophet

In Iran, journalist and filmmaker Nader Talebzadeh recently made The Messiah (2007), the story of Jesus told from an Islamic-Persian perspective. Here, Jesus is strong, beautiful, and revered as the last Jewish prophet who teaches and performs miracles, but is not crucified (he ascends to heaven instead, qua Islamic tradition). He is not the “Son of God.” The film has won awards, and Talebzadeh has been interviewed by several Western news outlets and provided strong arguments for the nature of The Messiah. In an ABC interview, Takebzadeh raises the question of the dissemination of religious ideas: “How do we export our thinking? It’s the movies. This is a film for students and for practicing Christians, for people to become curious, and go investigate more.” The filmmaker here gives credence for the worldwide export medium that film is, and also shows the ways multiple perspectives on Jesus can be seen.

Not Crucified, but “Disappeared”

The fourth and final filmic gospel comes from South Africa. But this is no gospel of John after three synoptics. Instead, director Mark Dornford-May has made Son of Man (2006), the story of Jesus set in present-day South Africa. The message of Jesus is thus shifted to a specific political reality and offers an alternative view of the messianic nature of Jesus. Jesus is black, as is Mary, Joseph, and the disciples, and their task is to work out salvation in a violent environment, a world probably resembling ancient Palestine more then anything shown in Euro-American versions of the Jesus story. Herein we find an annunciation scene, the healing of the sick (intriguingly, the “miracles” are always depicted through a video camera, handheld by Judas), and a resurrection. The dual nature of Jesus is clearly implied. Meanwhile one key distinction is that the crucifixion is private, as Jesus becomes one of scores of “disappeared” persons. It is only the work of his mother and followers that makes his killing public, thus serving as a testament to the ongoing importance of witnesses to political assassinations.

Readers may have never heard of these films despite each film’s prominence in its location of origin. And therein lies much of our Western myopia regarding religion, including the regard for images of Jesus. Yet it is not exactly the viewers’ fault: part of the reason Americans in particular don’t know these films is that each has struggled to find any distribution outlets in the United States. Understandings of religious issues continue to be regulated by distribution companies who control the media. But the films are available with a little research, and part of the interest in writing this is that we will take some time to find new channels of production, distribution, and translation.

Interreligious dialogue is one thing, but those of us interested in other religions must also realize that our very own tradition is not as homogeneous as we might like to imagine. There is even, we must ultimately admit, the possibility that our myths and rituals, our systems of behaviors and beliefs, are quite strange. And often it takes new translations, perspectives, and visions to allow us to see the strange as familiar and the familiar as strange. The Lenten season might then offer new perspectives on the mythologies, rituals, and textual accounts surrounding the figure of Jesus Christ.