Last summer I shopped around a satire about where Candidate Trump was leading America. Nowhere good. Written from the perspective of a father trying to explain to his daughter why she was no longer an American citizen, the retrospective retold the breakup of America along partisan lines, with progressive, multicultural coastal regions confederating with Canada, leaving behind a reddish rump Trump state whose relationship to the United States was rather like that between the Ottoman Empire and the modern Turkish Republic.

Editors didn’t bite. Trump as the nominee? Nobody believed it could happen.

And neither did I, really. The beleaguered minority hardly wants to imagine his country is so racist as to vote for the authoritarian demagogue in the ridiculous red cap. But here we are now, and what a sad reflection on our great nation.

Cue remorseful pundits interrogating themselves. So because Ross Douthat always makes me think, I looked forward to his essay for the Times, “The Party Surrenders,” the conservative columnist’s attempt to make sense of Trump’s victories. Douthat himself (and he is honest about this) didn’t think Trump stood a chance.

Here a remorseful, regretful, reflective Douthat argues that the GOP’s own infighting is largely to blame: “The Republican elite,” he writes, “was in the midst of a long-running civil war, pitting the much-hated ‘establishment’ against the much-feared ‘base’.”

Now he has the nomination, and the task of Republicans is to decide whether they will stand behind Trump, or against him and their party. Douthat wonders how this will play out—how Republican decisions right now will affect the party, and the country, in the future.

Which is when he jumps the shark.

Douthat reaches for an historical analogy, and this is the one—out of at least, say, 330,000,000 possibilities—he finds:

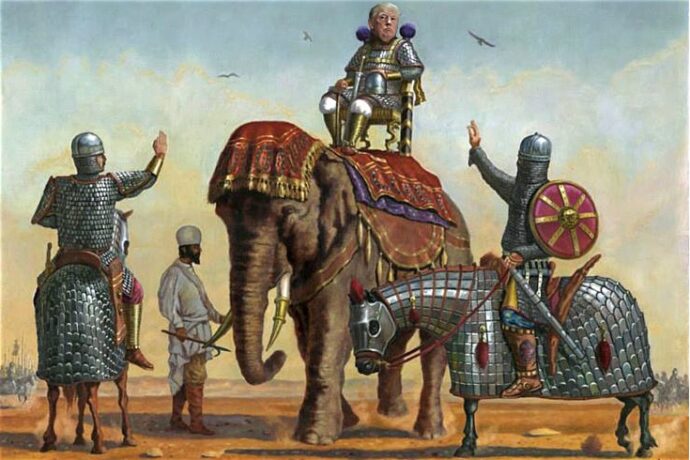

It’s possible that the establishment and the Tea Party are more like Byzantium and Sassanid Persia in the seventh century A.D., and Trumpism is the Arab-Muslim invasion that put an end to their long-running rivalry.

What these great ancient powers thought was “a temporary problem,” namely the invading Arab Muslims, merely “an alien force that would wreak havoc and then withdraw, dissolve, retreat,” turned out to be anything but: “A new religion had arrived to stay.”

The world was overturned.

With Trump on television so often, you hardly think you can be surprised by anything an American says anymore. But “The Party surrenders” was an instance of legitimate astonishment for me. In Arabic, Islam means “surrender”—as in, surrendering oneself to God. I’m not sure if that was a deliberate resonance, but the coincidence is telling. Because Douthat just compared the most Islamophobic candidate in American history to Islam.

Trump is the guy who, may I remind you (because I certainly don’t need to be reminded), wants to ban us (Muslims) from the country (with varying degrees of specificity and certainty, what is known in Arabic as “flip-flopping”), increase surveillance of us, detain or inter of us, offer us special IDs, torturing relatives of only those criminals who follow our religion—and let me just add, for every cake deserves its icing, approves of Muslims mass murdered by bullets bathed in pig’s blood.

And Douthat is reminded of Islam? Strange, yes. I could use stronger words.

The best historical analogy Douthat can find to the factionalism rending apart an American political party is a conflict between two great Middle Eastern superpowers, divided by religion, each intent on physically eliminating the other?

But it’s not a bad analogy, you see. It’s a Freudian slip of an analogy, revealing what Douthat is really thinking—and offering a surprising insight into what is actually going on. Because, as I’ll argue, Trump is kind of like seventh-century Islam.

But before I tell you how, let me just say that when Douthat makes an analogy that associates Trump with Islam it is because my religion represents in the modern American imaginary the ultimate other, the ne plus ultra of civilization. Douthat makes the association so as to distance himself, and his party, and his intellectual pedigree, from the demagogue who has now captured much of the territory he saw as his own.

You see, if Trump is an outside force, an alien invasion, whether here to stay or not, then your culpability is markedly reduced.

But Trump is not an outside force, and despite his color does not appear to be extraterrestrial. And just like I wish Obama would stop saying we should respect Muslim rights because we are America’s allies in the war on terror (we have no inalienable rights now, just instrumental ones) I would also like Douthat to know: Muslims do not exist in order to absorb the blame for someone else’s mistakes, analogically or actually.

Trump is the inevitable outcome of much of the noxious, racist, crass discourse that dominates on the right, and especially the alt-right, about which no better description can be offered than “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” The utter disregard for facts, evidence, difference, the wallowing in xenophobia, the encouragement of violence and aggression, the deep resentment, the feeling that everyone wrongs us and we’ve never wronged anyone—anyone who spends any time on social media will find Trump supporters convinced there is a white genocide underway; just look at his own longtime butler to see what swamp Trump emerged out of. This is, after all the candidate who got his start with birtherism.

And, sorry Ross Douthat, he’s a Republican. That’s the party he chose, but the Party, too, had a choice, and chose him, and every day more Republican elders are lining up behind him. It is unfortunate that, rather than own up to the indigenousness of the ugliness, Douthat attempts to find some other, foreign precedent for it, as if there our moral ignominy is ultimately derivative; it is no different from how many pundits will immediately call a despot an ‘Oriental despot,’ as if dictatorship is foreign to the Occident but native to the global south. When we make mistakes, they’re mistakes. When you barbarous others make mistakes, you’re fundamentally flawed. We are wrong when we are wrong. You are yourselves when you are wrong.

Trump came from America, and it is Americans who flock to him.

Which brings me to the unintentional illumination Douthat affords us with his peculiar analogy—and to this history lesson.

Historically speaking, yes, Islam’s arrival overturned an old order—but Islam emerges out of the same historical roots as that order.

Early Muslims were not a foreign force, or at least did not conceive of themselves as such. The Byzantines and Sassanids they eventually defeated had long kept Arab clients, while the Muslims who arrived with armies—at a time when there were no such thing as permanent state boundaries—saw themselves as the rightful heirs to the very ideologies their Persian and Greco-Roman opponents claimed. Early Muslims saw themselves as following the authentic message of Moses, Jesus and Zoroaster, and believed the Byzantines and the Sassanids were the interlopers; to an outsider, from a distant planet, it is hard to argue that the Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Zoroastrian traditions are so distinct as to represent different civilizations. To someone raised, for example, in a Hindu or Confucian milieu, these faiths probably seem to be disagreeable sects from the same messy tradition, the equivalent of subtitles that say “[Speaking Foreign Language]” or the way we say, “Chinese religions.”

“Near Eastern religions.”

Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads: A New History of the World is one of the best recent histories of the Muslim world, though of course, as the title suggests, that is not its primary purpose. Still, it’s hard to find good overviews and that is why I turn to Frankopan (and recommend you do). Do we find that the “Arab-Muslim invasions” were a Douthatian foreign force, a band of armed, undocumented immigrants bent on overthrowing Christian and Zoroastrian civilization? The evidence undermines the claim. Frankopan challenges Islamic supremacist narratives of this period of history, as well as anti-Muslim attempts to portray Islam as beyond the pale: “The messages of Muhammad and his followers earned the solidarity of local Christian populations,” he writes, describing how Muslim armies won over those they conquered—or persuaded clients of opposing empires to switch sides.

Frankopan writes that there was an ideological undercurrent of solidarity: “Islam’s stark warnings about polytheism and the worship of idols had an obvious resonance with Christians …A sense of camaraderie was also reinforced by a familiar cast of characters such as Moses, Noah, Job and Zacahariah,” not to mention “explicit statements that the God who gave Moses the scriptures, and who sent other apostles after him, was now sending another prophet [Muhammad] to spread the word.”

Probably neither Trump (nor his supporters) nor any sensible Muslim would be pleased by the comparison of the politician and the faith, and I for one still find it the kind of ill-advised stretch that results in catastrophic tissue damage. But in his haste to dump Trump on someone else, Douthat failed to notice the unintentional correspondence of the past to the present.

Islam is part of the historic three-way that is Abrahamic religion; it does not see itself as “a new religion,” nor was it, in its early history, very convinced that it represented a distinct tradition. That all happened later. More to the point: This is not a conflict between two powers which are eventually overturned by a billionaire upstart, but the nearly total victory of one side of a party over another. Trump might be radicalized, but he’s not a foreign fighter. If Trump were not reflective of what the Republican Party really is, then how could he so manage to so convincingly crush the Party, destroy its establishment, make mincemeat of its promising future leaders, and win so many states, and so many votes?

Just as Islamophobia didn’t come from nowhere, neither did Trump.

There are a lot of things Muslims have to face up to in the world, including what happens in the name of our religion. But Trump is not one of them.

Stop trying to abandon him, like the baby he is, at our threshold.