As a rule, you don’t refer to the political candidate you’re endorsing as “an untrustworthy figure, a volatile figure.” But that is just what R.R. Reno, editor of the conservative Christian magazine First Things, said in explaining his support for Donald Trump’s candidacy for president. As Reno explained on the First Things podcast from October 7, regardless of Trump’s profound flaws, “I do think it’s important to support someone who is at least willing to admit that we have really serious problems in our country.”

If that were all Trump were willing to do, then he would be a much better candidate than he is. But of course Trump would actually try to fix the problems he thinks we have, and he would suddenly have nuclear weapons in his toolbox.

Among Christian intellectuals, Reno’s pro-Trump nihilism is matched only by that of the writer Eric Metaxas. In an October 12 article in the Wall Street Journal, Metaxas writes in apocalyptic terms about a possible Hillary Clinton presidency, assigning her responsibility for things she has no control over, but still claims that “God will not hold us guiltless” if Christians allow her to become president. Never mind the apocalypse a President Trump would unleash.

Reno and Metaxas are supposedly among the best minds on the Christian Right. But their arguments for Trump are neither conservative, Christian, nor intellectual. They aren’t even patriotic, given that both Reno and Metaxas seem fine with allowing the country to be driven to ruin—just so long as Clinton isn’t the one driving.

The collapse of so many on the Christian Right into political resentment and Trumpism is lamentable, but it was also predictable. In fact, I predicted something like it in my 2009 book, Secret Faith in the Public Square. In it, I argued that American Christians were selling out their religious identity for cheap political gain, and that they could help ensure their religious integrity if they took that identity off the market altogether by concealing it in public life.

This approach would take seriously Jesus’ advice to pray in secret and to give alms without letting “your left hand know what your right hand is doing” (Matthew 6:3-6). It also would follow an undercurrent in Christian history that supports keeping your faith secret in order to keep it from being co-opted by your political or commercial life. I wrote that secrecy was “the only way [American Christians] can prevent the continued degradation of their religious identity.”

Reviewers found the argument clever and provocative but largely unconvincing, because they thought I had misdiagnosed the real dangers to Christian identity. One reviewer argued that ordinary Christians are in fact so reluctant to appear publicly as Christians that the real threat to Christian identity was the exact opposite of what I saw. Reno, whose signature rhetorical move may well be the backhanded endorsement, likewise wrote in a blurb for the book’s jacket that “Readers may not be persuaded.”

I grant that on the surface at least, the crisis in conservative Christian “witness” looks different today than it did at the end of George W. Bush’s presidency, when I wrote the book. Since then, I have rethought my strong stance in favor of secrecy. But the deep problem remains the same: by identifying their faith so strongly with politics, conservative Christians have married their self-understanding to the fortunes of the Republican Party’s presidential candidates. Even if that candidate manifestly aims only at self-aggrandizement, well, so be it.

In the Bush years, conservative Christians were triumphant—and triumphalist. They celebrated Bush’s election as a reassertion of America’s essentially Christian character. Richard John Neuhaus, the founding editor of First Things, wrote in 2005 that the secularization thesis—the idea that as cultures modernize, they become less religious—had been “debunk[ed]” and that the American secular revolution might be facing an antisecular “counterrevolution.”

Only a few years later, with Barack Obama in the Oval Office, conservative Christian intellectuals were telling the exact opposite story. The writer Rod Dreher now laments the “exiling of Christianity from public life.” Reno writes about the prospect of Christian “dhimmitude” (a popular neologism among Western conservatives that essentially refers to the subordination of Christianity in public life, deliberately evoking the specter of Islam). Following the Supreme Court’s 2015 Obergefell decision, which legalized same-sex marriage across the country, the conservative magazine National Review published an essay by the talk-show host (and Trump supporter) Dennis Prager headlined, “The Court Follows Its Heart and Completes the Secularization of America.”

Completes the secularization of America? That was fast. The men who lead the Christian Right seem to have a poor sense of history and politics. And despite their self-proclaimed allegiance to the U.S. Constitution, they see the presidency as a position equivalent in power to the Roman emperor, with every candidate either an absolute friend to the church or an absolute enemy. Metaxas therefore thinks that, to keep someone he sees as Julian the Apostate out of office, Christians need to throw their support behind Caligula.

Reno, Metaxas and others are not seeing things clearly, and by continuing to make apologies for Trump, they are making it impossible for Christianity to offer a public witness that doesn’t just coincide with strict partisanship. If being a Christian in America necessarily means supporting a racist, misogynist, xenophobic, untrustworthy and volatile wannabe dictator, then count me out.

I am not arguing that Clinton is the obvious choice for Christian voters—as if there were such a thing as the obvious choice—just that Trump isn’t it. And in fact, not every Christian conservative leader has twisted themselves into knots to argue for Trump. The Washington Post reported on October 9 that evangelical theologian Wayne Grudem had withdrawn his endorsement following the release of the tape of Trump bragging about sexual assault. The same article notes that Reno is, in his words, “beginning to regret signaling any public support, as you can imagine.”

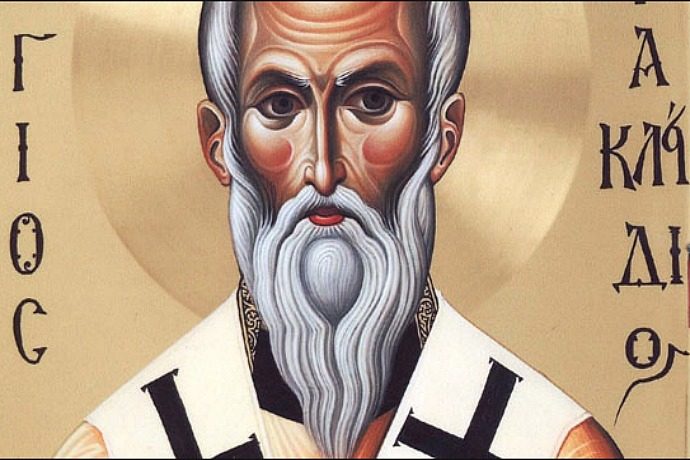

Back in the middle of the fourth century, when there really was a Roman emperor, the bishop of Jerusalem was wary of the new alliance between Christianity and the empire. Concerned that many people were seeking to join the church just to get ahead in imperial society, Cyril, the bishop, instituted an elaborate process of Christian initiation and began celebrating the sacraments only behind closed doors, in order to keep out those who were not full members of the church.

Cyril’s aim was to manage people’s identities: did they identify with Christ, or the empire? If they were committed to Christ, then they would express that commitment out of public view. Maybe secrecy is not the right prescription for American Christians in the present moment. But the wise discernment exhibited by Cyril certainly is, so that they do not render unto Caesar what is God’s.