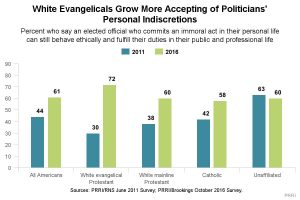

Five years ago, the Public Religion Research Institute asked Americans whether a politician who “commits an immoral act in their personal life” was still able to “behave ethically and fulfill their duties in their public and professional life.”

It was as if the question were written for Candidate Trump—years before Donald Trump had even decided to run for president! And, at the time, Americans weren’t thrilled with this imaginary, immoral politico. Just 44% said something along the lines of Yes, sure, the immoral officeholder will serve just fine. White evangelicals were even cagier, with just 30% getting behind the hypothetical sinner.

Things change. When PRRI asked the same question last week, 61% of Americans responded that a bit of personal immorality was’t necessarily a detriment to the record of good public servants. Among white evangelicals, the number was even higher—72%, or a 42 point increase over the 2011 data.

So has “[Donald Trump] changed all that,” as Jonathan Chait asserted, referring to evangelicals’ earlier views? Has the moral majority become the “immoral minority”? And is this a sign of a “sudden, massive shift” among white evangelicals, as one journalist put it on Twitter?

Not necessarily. Or, more accurately, it depends what you mean by “sudden.” For starters, it’s important to remember that the survey is comparing data from a non-election year (2011) with data taken less than a month before a presidential election.

When you ask a question like this in a non-election year, respondents are likelier to grapple with the question in abstract terms. They may also find it easier to lean toward an aspirational response—one that reflects the way they’d like to think of themselves. When you ask the same question in October 2016, though, respondents are going to answer with some concrete consequences at stake.

In other words, it’s not necessarily that people’s moral values have changed since 2011. It’s just that they hear the same question through a very different lens in an election year.

The lesson here is that evangelicals, like other voters, are willing to compromise, a willingness that has caught many observers off-guard this year as they flock to support a philandering, swearing, biblically illiterate candidate who boasts about sexual assault. Certainly, Trump’s support among white evangelicals is hard to reconcile with the ethical self-presentation of a movement that uses terms like family values and moral majority to imply its uncompromising commitment to certain principles.

But the assumption that white evangelicals actually were once paragons of moral rigor seems pretty questionable.

I’m not trying to impugn white evangelicals, exactly. The point is that white evangelical voters, like all other voters, are likely to bring a whole range of considerations, affiliations, prejudices, concerns, identities, and aspirations with them into the voting booth. Some of those identities and concerns will have more direct scriptural roots, but many others will not. When a white, evangelical, rural, middle-class, heterosexual Republican woman in Kansas goes to vote, it’s not clear why her concerns will only take shape along a biblical-theological-moral axis, versus all the other concerns that people bring into politics. It’s not even clear that “evangelical concerns” are themselves easily classified as biblical and/or theological.

As noted earlier, the dramatic change among evangelicals documented in the PRRI poll may be more a matter of aspiration than change. Rather than having somehow been “Trumpified” into betraying their ideals, evangelicals may simply not have much of a problem pulling the lever in opposition to their previously stated preference when there are consequences on the table.

The simplest interpretation of this year’s political rollercoaster is that, after all the hand-wringing, Republicans are still voting for a Republican. And, as the PRRI survey question reminds us, it’s that, in an election year, everybody ends up making compromises.