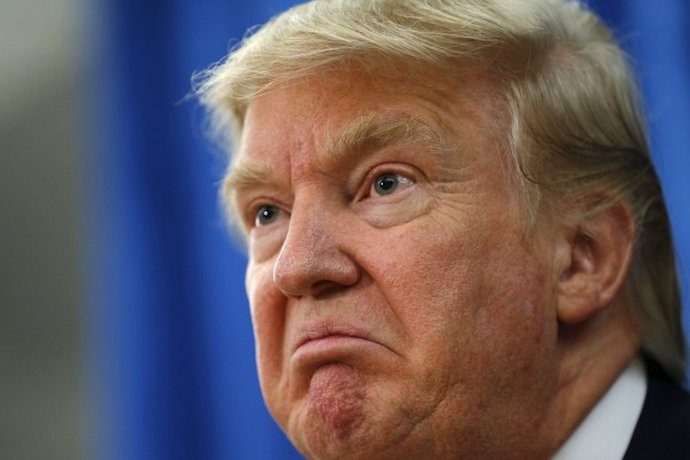

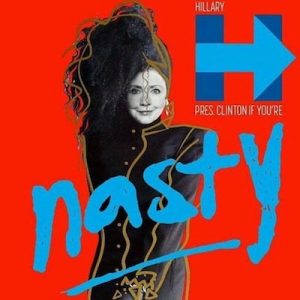

“Such a nasty woman.” Trump’s seething comment at last Wednesday’s presidential debate was instantly turned into a hundred hashtags (e.g. #ImWithNasty) and a thousand memes (many involving Janet Jackson, whose song “Nasty” shot up the charts on music streaming services in the wake of the debate). Yet despite these attempts to own the term on social media, the word “nasty” bothered many women, who rightly saw it as an attack on themselves. Trump wasn’t saying that something Hillary did or said was nasty, he said she was nasty. If she is nasty, so are we all.

“Nasty” may be heating up recent Twitter feeds but its corollary “disgusting” is the most revealing of Donald Trump’s descriptors. He uses it so often it’d be impossible to catalog. “I know where she went, it’s disgusting, I don’t want to talk about it. No, it’s too disgusting. Don’t say it, it’s disgusting, let’s not talk” (of Hillary Clinton). “I’ve never seen a human being eat in such a disgusting fashion” (of John Kasich). “(His sweat) is disgusting. We need somebody that doesn’t have whatever it is that he’s got” (of Marco Rubio).

“Nasty” may be heating up recent Twitter feeds but its corollary “disgusting” is the most revealing of Donald Trump’s descriptors. He uses it so often it’d be impossible to catalog. “I know where she went, it’s disgusting, I don’t want to talk about it. No, it’s too disgusting. Don’t say it, it’s disgusting, let’s not talk” (of Hillary Clinton). “I’ve never seen a human being eat in such a disgusting fashion” (of John Kasich). “(His sweat) is disgusting. We need somebody that doesn’t have whatever it is that he’s got” (of Marco Rubio).

Urination, perspiration, menstruation, mastication, lactation—all these functions of the body are disgusting to him. But he also frequently calls people, especially women, “disgusting” as when he recently tweeted: “Did Crooked Hillary help disgusting (check out sex tape and past) Alicia [Machado] become a US Citizen so she could use her in the debate?” In this tweet, as in the debate, it is the woman herself who’s disgusting and nasty. The person of Rosie O’Donnell also disgusts Trump; so deeply in fact that he can’t help but bring her up regularly, as he did during the first debate (though she hasn’t been a television regular for close to a decade). His disgust still feels fresh.

Trump’s fixation on disgust and its social and political implications has not gone unnoticed, with the New York Times and the New Republic (among others) having previously written about it. Disgust is both an emotional and visceral response to something that we fear will contaminate us. Rancid food, a decaying corpse, an infected wound—all these call up feelings of disgust in human beings, as do body fluids like blood, semen, saliva, and breast milk. We are disgusted when what’s inside the body comes out.

Although these responses to such stimuli may be biologically based—a mechanism for human beings to protect themselves and their health—a recent study found that disgust is not politically neutral. In fact there appears to be a strong correlation between disgust sensitivity and political conservatism, and it’s a particularly strong predictor of anti-immigrant attitudes among voters. It isn’t just about biological contamination, it’s about social contamination. We are often disgusted by the other, by human beings who are different from us—who look different, who eat different, “disgusting” foods, whose cultural and personal habits and ways of being we don’t share.

In her book, Disgust and Humanity, (Oxford, 2010) Martha Nussbaum argues against disgust-based morality and legislation of the sort that has often been used to justify laws against interracial and gay marriage, on the grounds that disgust is an unreliable emotional reaction that causes individual and social harm when applied to legal contexts. She identifies disgust as a bias with no place in the legal system. But for Christians, in addition to being a social and legal issue, disgust has a theological dimension—one we might all benefit from thinking through.

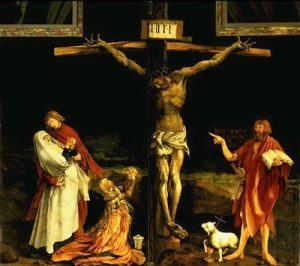

“The Crucifixion” by Matthias Grünewald ca. 1480 – 1528.

The incarnation of Jesus, the idea that God became a human being (really and truly) has profound implications when it comes to the rhetoric of disgust. If Christians believe that God took on a human body, then they may no longer be disgusted by those bodies without blaspheming God. The Incarnation should mean that all human bodies have dignity and worth—fat bodies and old bodies and brown bodies and diseased bodies. If Jesus was a human being, then he had a human body with all of its functions. He had a body which sometimes became ill, and a body which died.

The famous crucifixion panel of The Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grunewald shows an emaciated and ghoulishly pallid Christ, his body covered with sores, ragged wounds on his hands and feet, in a state of decay too advanced for someone who had just died. Grunewald’s Christ could certainly be called disgusting, as the patients in the monastery hospital for whom the painting was commissioned surely were (a hospital which specialized in The Plague and skin diseases). Its attention to the “disgusting” aspects of Jesus’ death may have served a psychological and theological purpose, sending a vivid message that disgust at human decay, disease, and death had been transformed by the Incarnation. We can imagine that when those patients and the monks who cared for them looked upon the altarpiece and saw God in the same state they were in, their condition might have been elevated and granted dignity.

Also, Jesus himself rejected disgust. He elevated the Samaritan, the ultimate “other” to the highest moral position in all of the Gospel stories. He associated with lepers, and in Luke 17 he cured ten of them, with only the Samaritan, the foreigner, remembering to thank him. The story that most speaks to Jesus’ rejection of disgust, however, is one involving a woman’s body, the kind of body which is most often labeled “nasty” or “disgusting.”

In Mark 5: 25-34 Jesus heals a hemorrhaging woman. This woman had been ousa en rhusei haimatos, or in a state of blood flow, for 12 years. To be clear, this is menstrual or uterine blood, another disgust trigger for Trump. This woman’s condition would have disgusted her community. She would have been in a permanent state of ritual uncleanness. Her mere touch would have defiled Jesus, but Jesus was not disgusted by her. In the story he feels her touch on the hem of his gown, heals her of her terrible affliction, and calls her “daughter.” Not once does he call her “nasty.”

Many of the great Christian saints also understood the theological imperative of rejecting bodily disgust. St. Francis, from whom the current pope took his name, was overwhelmingly disgusted by lepers as a young man, but as part of his conversion he was “made stronger than himself” and kissed a leper he met on the road. St. Catherine of Siena, St. Elizabeth of Hungary and many other saints cared for the sick, those who were too disgusting to touch, and brought themselves into intimate contact with the physical realities of infection and cancer. They understood that disgust for human beings has no place in the Christian life.

Donald Trump seems to live in a near permanent state of disgust. He finds not only the human body but human beings “disgusting” and “nasty.” Disgust is part of what allows him to revile and dehumanize people regularly. It fuels his hateful rhetoric and policy on immigration. Calling Hillary Clinton “nasty” or being disgusted by Megyn Kelly or Alicia Machado isn’t only unkind, rude, and sexist—though it is those things—but it’s also incompatible with the universal Christian doctrine of the Incarnation.