Pastors and lay leaders who represent minority and multiethnic communities and are appalled by the prospect of a Donald Trump presidency have a blunt message for the white evangelical majority that helped elect him: we’re disappointed in you, but not surprised.

For these evangelicals of color, Trump’s use of racially-charged language, his anti-immigrant rhetoric, negative remarks targeting Mexicans and Muslims, as well as the emergence of the “Access Hollywood” tape and his other divisive comments about women, were simply disqualifying.

Aaron Cho, an associate pastor at Seattle’s Quest Church, works in a vibrant multiethnic, multiracial congregation that, he says, embraces women in leadership positions, affirms refugees, and embraces racial reconciliation. “These are all core convictions that we have had for years” he tells RD. “It was really hard to navigate seeing his platform getting so much support when it is contrary to the message of Jesus.”

The Rev. James C. Perkins, President of the Progressive National Baptist Convention (the denominational home of the late Martin Luther King), and pastor of Detroit’s Greater Christ Baptist Church, says that he was taken aback that white evangelical leaders who supported the president-elect “were not sensitive to issues of justice and character. I think the white church has to do some self-examination to see whether they are in line with the Gospel or just pushing a civil religion.”

While some prominent white evangelical leaders made their opposition to then-candidate Trump widely known (many signing a letter protesting his candidacy), the majority of white self-identified evangelicals (estimated to run as high as 81 percent), lined up behind him.

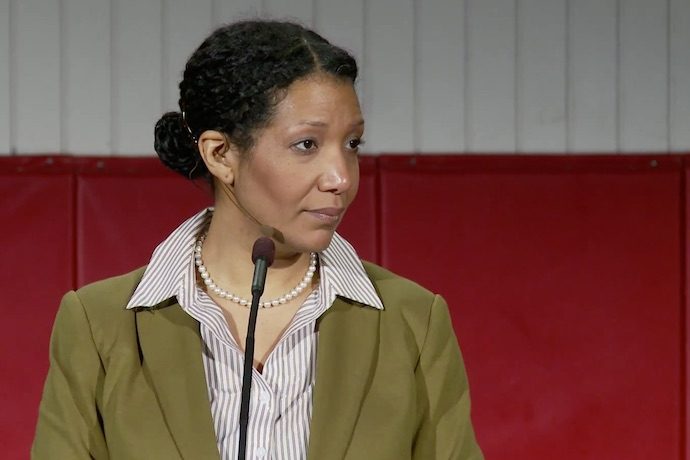

“Many of [Trump’s] critics fell silent or fell into line, while the group known as the ‘religious right’ continued to support him’ says Kathy Khang, a Christian writer and speaker based in the Chicago area.

When asked about the outspoken remarks of popular Christian writers and speakers like Jen Hatmaker, Khang says that she wishes they had spoken up when Trump was making derogatory comments about immigrants and African Americans: “It was great when evangelical women started speaking out. It’s just unfortunate that it took them so long and that it took that [the ‘pussy-grabbing’] comment.”

Calling Trump’s behavior on the campaign trail both “disturbing” and “frightening,” Khang adds: “My reaction was one of disappointment and honestly deep concern for myself and my family and my friends. It left me wondering if it’s worth continuing to call myself an evangelical, because white evangelicals have shown their support for him.”

For the past eight years, people of color, the LGBT community, and women have been given license to flourish, says Lisa Sharon Harper, author of The Very Good Gospel: How Everything Wrong Can Be Made Right and chief church engagement officer at Sojourners. “The white church demonstrated on November 8th that it is more white than Christian, and has a [greater] commitment to white supremacy than it does to Christ,” says Harper.

The fact that so many evangelicals didn’t see Trump’s controversial rhetoric as derogatory underlined the presence of a persistent and troubling racial divide in American Christianity that these leaders say is deeply rooted in American history.

Referencing sociologists Christian Smith and Michael Emerson’s 2000 book Divided By Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America, Harper described a white evangelical church that is structured in such a way as to keep others out. It creates an alternative life for its congregants, one based on church growth models that create “huge churches full of nothing but white people, an enclavish culture where you can literally live your whole life and everyone in your church is just like you. You end up creating a situation in which your world view is affirmed and confirmed by everyone again and again.”

Some are questioning the value of continued association with the white evangelical majority.

While there are pockets of “progressive” white evangelicals with whom African Americans have good working relationships, says National Black Evangelical Association President and pastor Walter A. McCray, most other white evangelicals trend conservative, or even further to the right, putting them “miles apart in some of their values and theological understanding. It’s a strain for many African-American evangelicals…what do African Americans gain in associating with white evangelicalism as it has been hijacked by the right?”

“In other words,” says McCray “those who identify as black or African-American evangelicals must bend over backwards to explain who they are.”

Despite their dismay over the prospect of a Trump presidency, those I spoke to appear to be more motivated and energized than daunted by the challenges that lie ahead.

“I think this is a natural process that occurs when a country has not dealt fully with its own true story” says Rev. Joshua DuBois, who headed the Office of Faith Based and Neighborhood Partnerships during Obama’s first term. “We are a country that has deep challenges related to race, gender and economics. While things have certainly gotten better over time we have not done a lot of introspection about our character—thus, we see the spasms and backlashes that have occurred and will occur as we grow and change.”

“This has been a wakeup call to the progressive, moderate community that we have to stand up for what we believe in and communicate it in the public square,” DuBois concludes.

And Lisa Sharon Harper tells me that “a new Civil Rights movement is happening, and its locus is in people of color.” She sees evidence of it already in the “movement for black lives,” the witness of the so-called “Dreamers” (undocumented immigrants who arrived here as children), and the rising call for solidarity with the poor that mirrors the words of Jesus in Matthew 25. “Every word of Scripture was written by oppressed people,” she says.

“My people were shocked and for a minute they were fearful as to what was going to happen” says Perkins of his congregation. “That shock and fear has subsided, because we are people of faith and ultimately we know that our trust is in God.”

“We are angry, we are grieving, we are organizing” says Khang, who challenges white evangelicals to listen to the concerns of evangelicals of color with more care and sensitivity. And to those white evangelicals who opposed Trump and are now considering casting off the evangelical mantle as a mark of shame, she has a tart rejoinder. “Leaving a label is one thing, but changing an understanding of what is Christian or Christ-like is another. Why do I have to leave? Why don’t you stick around and fix this mess?”