I make no secret of being old, white, male, and Protestant.

Christmas to me has always been a very big deal. Even now, and even especially now in the pit of winter and on the cusp of our unsought descent into Trump Time: all those tidings of great joy, all those angels heralding the dawn of new hope and light, mean more to me than my rational mind can quite comprehend.

The season gets to me mainly by means of the incredibly rich sacred music written under the Advent sign. The wild pounding of kettle drums that opens Bach’s “Christmas Oratorio” never fails to give me goosebumps of joy and anticipation. Likewise the grand dance tune that Handel, the sly old fox, puts under Chorus 12: “For unto us a child is born.”

I could go on: there is really no end to the depth and glory of the Advent music created from at least the 12th century forward. And don’t get me started on the painting and sculpture.

Never mind that JC’s birthday was arbitrarily (and brilliantly) assigned to Dec. 25 in order to go one-up on an important Roman festival time. And never mind that the New Testament’s nativity narratives don’t cohere and were quite obviously invented to supply a back story for the main event in the consciousness of the early church, which was the death and resurrection of the short-lived Galilean, not his birth.

I happened to be among my colleagues in a social justice project planning meeting this week when a good friend, a pastor whose worldview was shaped in the anti-apartheid struggle in his native South Africa, spoke of “praying with our eyes open in the spirit of Luke,” a clear reference to Luke 3 and John the Baptist’s proclamation: “And all flesh shall see the salvation of God” (an utterance adapted and improved, for oratorio purposes, in Jennens’ libretto as “and all flesh shall see it together.”) The frame for all of this being Isaiah 40, a central messianic text in the Hebrew Bible.

But wow, where to begin with the problems for relations with others in the Abrahamic faiths, let alone all the non-Abrahamic ones. This is a short post. There’s a vast literature laying out all the problems.

Here I want to point not so much to the problems posed for the interfaith enterprise but rather to what might be called the internal problems posed by a partially realized eschatology. Liberals like me can’t really bring ourselves to believe that Christ will be coming again in glory. This means we have to settle with what we’ve got: a man who showed us what God is like in the brief span of a still-obscure life long ago. And yet everything about the man and his message has to do with the actual inauguration—yes, the advent—of the Reign of God. Thus, in the Magnificat, the use of the past tense is critically important:

He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts;

he has brought down the mighty from their thrones

and exalted those of humble estate;

he has filled the hungry with good things,

and the rich he has sent away empty.

For this to mean anything is to accept that power relations have already been decisively shifted by virtue of Christ’s birth. Yet clearly they have not. It’s still “truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne,” as James Russell Lowell’s words for the old hymn put it.

If we try to cover over this problem with the hoary old “already…but not yet” formula, we are back in the fantasyland of expecting Christ’s glorious return in judgment. But if we try to convince ourselves that the Incarnation has already made a decisive difference in human history, we are equally delusional.

We are thus left with a weak-tea mysticism: the idea that somehow, and in some way, we as “Christ’s body” in the world are still bringing God’s Reign into fruition—just very, very gradually and imperceptibly.

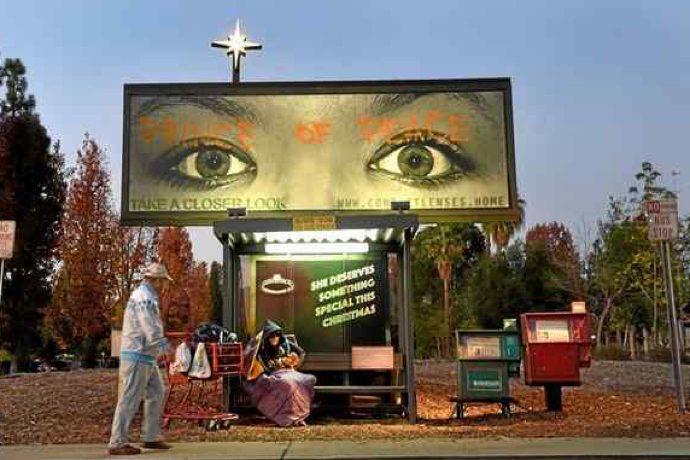

What I’m saying: the gorgeousness of the seasonal fanfare, the splendor attending to the Savior’s birth, and the reality of our diminished hopes for deliverance just don’t align very well. Never have and never will. This is hardly a new insight. Those of us who want to believe are still forced to posit that something further may yet happen, as we trudge along for the time being, as per Auden’s memorable Christmas poem.

To be clear, I am not complaining. What Coleridge, in another context, called “the willing suspension of disbelief” still works for me at Christmas. I’m just left wanting more.