Instead of opening presents first thing Christmas morning, I opened the New York Times. Inside was a column by well-intentioned liberal Nicholas Kristof headlined, “Pastor, Am I a Christian?” The Wringing of the Hands is not a holiday tradition in my family, so I turned away without reading it.

I returned to it in the New Year, after the Times published a slew of letters in response—letters debating, of all things, Christian doctrine. In the original column, a dialog between Kristof and the evangelical pastor Timothy Keller, Kristof’s aim is to understand which articles of faith, if any, are indispensable for someone calling him or herself a Christian. Keller argues that they all are.

Kristof, who identifies as a Christian—albeit “not a particularly religious” one—repeatedly questions traditional teaching by pointing to the apparently plain language of the bible itself. For example, he notes that “the earliest accounts of Jesus’ life, like the Gospel of Mark and Paul’s letter to the Galatians, don’t even mention the virgin birth.” Kristof is no theologian, but he doesn’t see why he has to accept this particular Christian teaching. If a smart, well-intentioned person reading the bible doesn’t come away from it convinced of the virgin birth, then what’s the problem?

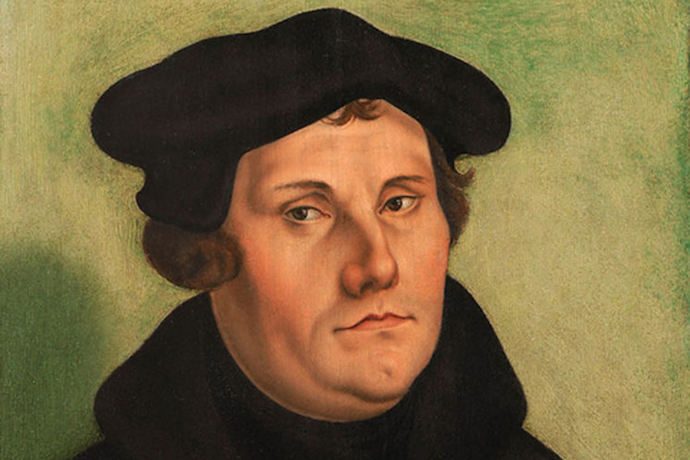

In trusting his own reading of scripture ahead of what centuries of theological experts have maintained, Kristof makes the quintessential Protestant move. Martin Luther published the bible in German in part to undermine papal authority. In his view, any believer should be able to interpret scripture, not just the clerical elite.

Like many great innovations, Luther’s had severe unintended consequences. In their efforts to level the ability to interpret the bible, Protestant groups struggled to maintain doctrinal unity and so splintered again and again in the succeeding centuries. Without a magisterium to keep belief within bounds, they often looked to the state to police doctrinal adherence.

Luther distrusted expertise. Now, for those on the American political right, you might call distrust of expertise an article of faith. And President-Elect Donald Trump has taken that distrust to the furthest extreme, repudiating expertise altogether with his repeated refrain, “Nobody knows what’s going on.”

On virtually every issue, from immigration to the Incarnation, Trump puts no faith in experts. His own “very good brain” supposedly provides better counsel than any foreign-policy advisor could. Buoyed by fake news stories, Trump’s popularity reflects the worst of the Protestant Reformation: the fragmentation of knowledge regimes, and an appeal to coercion to enforce orthodoxy.

Trump’s heterodox instincts even extend to his selections for who will lead prayers at his inauguration this month. Two of the six religious leaders slated to pray at the event preach the prosperity gospel—the idea that following Jesus is the path to riches. One of those two, Paula White, teaches that Jesus is not, as the Christian Nicene Creed has stated for 17 centuries, “the only-begotten Son of God.” According to her, any of us could earn that title.

Some prominent evangelical leaders object to the platform Trump is giving to people they see as outsiders—even heretics. Liberal Christians suddenly find themselves arguing for stricter orthodoxy in other areas, too. Progressive Christians lament that white evangelicals, 81% of whom voted for Donald Trump, put their whiteness ahead of their religious commitment to moral decency, repentance, or care for the poor on Election Day. Why didn’t they consider the essential teachings of the gospel? Why didn’t they listen to Russell Moore, or a progressive pastor like William Barber III?

The answer is simple enough: they’re Americans. The sovereignty of individual conscience, awakened by Reformation-era distrust of knowledge experts backed by political power, was an essential component of the revolutions that created modern democracy.

But that same sovereignty now threatens to fracture our democratic polity. Seemingly every sphere of knowledge expertise—science, the news media, and even the national intelligence services—is currently distrusted by those on the political right. They have ridden that distrust to power on every level of government.

In response, Democrats have emerged as the party of deference to experts: to scientists on climate change, to teachers on education, to the CIA on cybersecurity. (In theological matters, however, as Kristof shows, free thought still reigns.) On balance, this is the right course to take; it exhibits the intellectual humility that even a well-educated citizenry must have. Of course, even if Republicans have taken an otherwise healthy skepticism to a mad extreme, Democrats should take care not to become fanatically loyal to an infallible elite.

One hopes, for the sake of American democracy, that we can together strike a wise balance between suspicion and deference with respect to expertise. The greater danger right now is brazen suspicion run amok. Unfortunately, as the history of the Reformation shows, once independent thought is set free, it’s hard to tame it again. Add depoliticizing expertise to the long list of challenges we face in the upcoming presidency.