I was encouraged this week when I read an op-ed column in the London Observer by former President Jimmy Carter. Some may remember that about ten years ago Carter resigned from the Southern Baptist Convention after it had issued a number of rulings on the role of women in the church and society. Women, it said, needed to be subject to men. We were responsible for the sin of Eve and we could not be deacons, chaplains or ministers in the church. It was a boost for all women working for women’s rights in the churches when Carter stood up for us.

Now, Carter has joined with other world leaders and initiated a project aimed at ending religious discrimination against women and girls.

Carter was writing as one of a group of a dozen world leaders organized two years ago by Nelson Mandela. The Elders, as they call themselves are, well, older and out of public office. They bring their stature and wisdom to the intractable, often unpopular political issues of our time and seek not to solve them but to make them more visible and discussed. They support peace building, seek to end human suffering and “promote the shared interests of humanity.” Now they are taking on religious and traditional practices that harm women. On the Elders’ website they “call on men and boys—and particularly religious and traditional leaders—to change harmful and discriminatory practices against women and girls.” Fernando Henrique Cardoso, the former president of Brazil says “the idea that God is behind discrimination is unacceptable.”

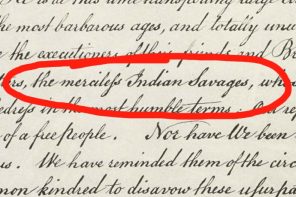

But Carter’s Observer article issues the most direct challenge to religion. Religious discrimination against women has, he says “ provided a reason or excuse for the deprivation of women’s equal rights across the world for centuries. The male interpretations of religious texts and the way they interact with, and reinforce, traditional practices justify some of the most pervasive, persistent, flagrant and damaging examples of human rights abuses.”

Carter and the Elders are equal opportunity critics. No country or religion, no practices go uncriticized. Discriminatory religious beliefs are described as “repugnant.” They are used to excuse “slavery, forced prostitution, genital mutilation.” They cost women and girls “control over their own bodies and lives.”

The US is not let off the hook. Carter links the flawed conservative interpretation of scripture as the kind of “discriminatory thinking… behind the continuing gender gap in pay and why there are still so few women in office in Britain and the United States.”

Carter is joined in his critique by other Elders, Desmund Tutu, Gro Bruntland, Mary Robinson and Graca Machal among the dozen elders. Their commitment to women’s rights and equality is not a surprise. The issue is high on the international development agenda. What is encouraging is the willingness of world leaders to single out religion itself as a problem and to criticize the interpretations of texts from the Bible to the Koran as part of the problem. Carter says he understands, “however, why many political leaders can be reluctant about stepping into this minefield. Religion, and tradition are powerful and sensitive areas to challenge.”

It is this acknowledgement that most encouraged me. It also highlighted that theory of change that holds that change occurs not at the center, but at the margins. None of the Elders is currently in “power.” Take Kofi Annan. When he was Secretary General of the UN, he was simply not able to speak his mind. He was an advocate for women, but careful not to critique religion. That applies to non-governmental leaders as well. The closer you are to power, the more you have to lose and the more careful you are about being “negative.”

Many women working for women’s equality in both church (temple, synagogue and mosque) and society, have made the point that unless religious teachings change equality will be hard if not impossible to achieve—and that is not just true for women living under Muslim laws, but for women in the US. Getting male (and some women) religious leaders to agree has been tough sledding.

There is, in fact, some tension within the progressive religious movements here in the US. Granted, the repetition of the differences between various strands of progressivism in religion is getting tiresome but women especially find the more establishment progressive agenda lacking in a gender lens as well as a commitment to work for the changes within religion that are needed if we truly want a just America.

Carter’s op-ed and the Elder’s campaign provides a global framework that could be adopted and adapted by progressive religionists in the US. The willingness of religious progressives to combine the three strands of work most progressives are engaged in—social justice, spiritual renewal and the reform of religious institutions is just what we need.