Philip Clayton’s wonderful essay on the troubled relationship between religion and science represents one of those superlative and subtle interventions for which I have come to rely on him. Sly and suggestive, stunning in its breezy historical range, Clayton’s essay offers us, in the end, a fairly simple message about the urgent need for thoughtful and creative dialogue, across the disciplines. I will return to that second idea—creativity—in a moment. I also want to locate the academic study of Religion more explicitly within the Humanities, for reasons that I hope to explain below.

The trouble with the current impasse is that it feels and sounds for all the world like children arguing in the sandlot about who started a fight. The scientists are still crying “foul” over what was done to Galileo by the Vatican (forgetting that he did some of this to himself). The new traditionalists are still crying “foul” at Modern philosophers and scientists for jettisoning the Aristotelian tradition of enquiry (forgetting that their own internecine squabbles had a lot to do with that).

The religionists these days—and they are legion—are crying “foul” over everything, from scientists who gave us the Bomb and global warming (which sounds eerily akin to Germans, Poles and Russians blaming Hitler for killing the Jews), to the alleged atheism of their scientific and empirically-minded default position (if you can’t see it, then you won’t be able to prove it), to the fact that so many contemporary scientists, especially the popularizers, seem hellbent on making religion look dumb.

Carl Sagan, arguably the most successful of all such popularizers, was located firmly in that camp. When invited to give the Gifford Lectures in 1985, he deliberately turned William James’s famous lecture course upside down, titling his reflections “The Varieties of Scientific [not Religious] Experience.” Science, Sagan suggested not-so-subtly, was the new religion. That was nearly 25 years ago.

What strikes me about our current sandlot slugfests, apart from the often childish rhetorical excess and general vitriol, is that so much of it hinges on origins: that is, the question of who started this fight. Such questions are akin to the logic of the blood-feud, and such feuds are impossible to resolve in their own terms.

Thus there is a subtle tension in Clayton’s superb history lesson: If we grant the importance of this move to the narrative history of the conflict, then don’t we run the risk of inviting, and even encouraging, the continued questioning about who started this cultural/intellectual free-for-all?

As a student of Greek tragedy, I recognize that the question of who started a cycle of senseless violence, vendetta and revenge-killing does not get the respective parties anywhere. Everybody has a legitimate grievance, everybody can allude to an historical grievance (if not quite an originary crime), everybody has a reason to feel aggrieved and angry now. Greek drama suggests that, in order to escape the logic of such cyclical violence, we need to escape the clutch of our historical obsessions, to stop looking for the origins of a fight, and start looking for how to end one.

The dramatic orientation is aimed at a better tomorrow. Greek tragedy is ironically aimed at that future, not the past.

Philip Clayton, too, invites us to imagine a different, and more conversational, and more collegial future. We are in his debt for this.

What I would like to suggest is that we might turn to the fine arts for guidance in these endeavors as well. Greek drama, after all, was a religious art-form intended and understood to be an intervention in some of the most divisive and agonizing battles of the day. It was unblinking in facing the problems; tragedy begins with agony, and often involves one or more deapossibilities for a better and more peaceable tomorrow. That is the mission to which Clayton calls us as well.

I am currently a professor in a College of “Arts and Sciences.” Clayton and I were once colleagues in a School of “Arts and Humanities.” (He is thus a dear friend as well as a valued colleague). I mention that in order to note the presence of the Arts as the ironic (and too often unnoticed) mediating institution between the Sciences and the Humanities. And in so saying, I am calling for a narrower, and more local, history to supplement Clayton’s deftly articulated, and far grander, one.

In a marvelous position paper delivered as a lecture in 2007, Vassilis Lambropoulos, nominally a Professor of Modern Greek Studies but in fact a polymath who writes about tragedy, literature, philosophy and current socio-cultural trends, posed a poignant question, “What Happened to Theory?”.

His answer is intriguing. As late as the1930s, he notes, most public intellectuals wrote about Art as if Art still mattered, and accepted some version of the great Modern idea that Art aims at conceptions of the good (occasionally, even the true), and that the aesthetic realm provided a form for the age under discussion. By the early 1980s, Lambropoulos suggests, the intellectual scene was hard at work in what he calls “the dissolution of the aesthetic realm.” (Sagan delivered his Gifford Lectures in 1985, and the Reagan administration had been gutting the National Endowment for the Arts for four years by then).

The consequences of the collapse of the Aesthetic as an independent sphere of enquiry, and the marginalization of the Arts, has been dramatic. Note that last point: the marginalization of the Arts, not Religion. By 1985, religion was decidedly back.

Lambropoulos observes several trends that resulted from this; I will rehearse only three of them.

1) “The return of the subject, this time as identity.” We do not approach the subject of the relation between religion and science as individual enquirers, but rather as representatives of a position—as scientists, as religionists, as Christians, Jews, atheists, or what have you.

2) “The return of ethics, this time as politics.” We do not turn to the Academy or the Art-world for experimental engagement in the divisive issues of the day, nor even to grassroots activism. No, we make each of these issues a matter of grand electoral politics and limit our strategic engagements to the political, broadly and nationally conceived.

3) “The return of empiricism,” which Lambropoulos continues, does not content itself with particular case-studies, but actually “rejects the grand narratives of traditional humanism.” In other words, and in the context of our current topic, the Humanities (religionists among them) gave away the very ground for which and on which we should have been fighting. We still have a foot in the world of Enlightenment values, including science, but we have a foot in the world of Romantic creativity as well.

And with that, may yet come a new perspective on the great spiritual questions of ours, or any, age.

It is often suggested that “science is the new religion,” and there is much to counsel the acceptance of that point of view. Carl Sagan took it as a given. Whether this means the death of religion or not is beside the point.

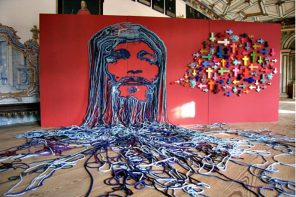

I would like to offer the counter-thesis, primarily intended as a thought experiment and friendly amendment to Clayton’s essay, that “Art is the new religion.” And that we in the Humanities and Sciences alike should remember to (re)turn to the Arts as we continue to try to imagine new and creative ways out of the current impasse, new ways to engage the Sciences and the Humanities in common enterprises—whether they be political, ethical, or aesthetic.

I eagerly anticipate Philip Clayton’s subsequent columns on specific case studies of the current state of the Religion-and-Science divide, and would welcome further the Aesthetic realm in these debates.