Ten Questions for Caleb Smith on

The Prison and the American Imagination

(Yale University Press, 2009)

What inspired you to write The Prison and the American Imagination? What sparked your interest?

I’ve always been intrigued by questions of discipline, solitude, and self-consciousness. American literature provides the richest language I know about for thinking through those questions. The prison provides a concrete historical context. In our age of convict warehousing and scandalous war prisons, it can be hard to remember this, but from a certain point of view, the prison system began as an experiment in how convicts could be rehabilitated and redeemed by a disciplinary institution.

The reformers who built the model institutions of the early nineteenth century called them penitentiaries, to compel penitence. They drew from Christian traditions—Quaker tenets of nonviolence, Catholic and Calvinist varieties of asceticism and moral rigor—and they often represented the cell as a place of spiritual rebirth. As a precondition for that resurrection, they led convicts through mortifying processes including “civil death,” a loss of legal personhood with origins in European monasticism. The Philadelphia reformer Benjamin Rush quoted scripture in describing the rehabilitated convict as a man who “was lost and is found—was dead and is alive.” My book is animated by my fascination with this resurrection plot and all of its contradictions.

Of course there are also personal kinds of inspiration. When I started writing it, in graduate school at Duke, I was living in a house full of amazing people, including one who is now a public defender and another who is writing about interrogation and confession in modern Ireland. It was just after September 11, 2001, and there was a feeling of political intensity. We were all very aware of living in history, in a world of conflict and real power. We talked all the time about crime and punishment. My book was inspired in many ways by those conversations.

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

The American prison has become a disaster and a scandal in recent years. My book tries to show how powerfully the prison has shaped American culture over a longer history. The prison has been a source of gothic nightmares but also, more surprisingly, a scene where we have rehearsed some of our most cherished fantasies: about the individual’s capacity to remake himself or herself through discipline, about a society’s power to remake itself through humanitarian reforms.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

There is a vast, rich archive of writing about prisons in America, much of it written from inside the walls, and I was only able to present a few examples. When I look back over the chapters now, I wish I would have paid closer attention to writings by and about incarcerated women in particular. The book tries to tell a story of two centuries in just over two hundred pages, so there is much more to be said. The good news is that all kinds of other writers and scholars are turning their attention to the prison in recent years. I’m still involved in other related projects too, including the Web site Imagined Prisons.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

Most people seem to assume that the prison is eternal and inevitable. My students are often surprised to learn that punishment has a history: that the modern prison was invented as a response to certain social and philosophical changes around the turn of the nineteenth century. Partly because the prison is so deeply aligned with the dream-life of power in America, it is very hard to imagine alternatives.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing? Are you hoping to just inform readers? Give them pleasure? Piss them off?

The book is for people seriously interested in American history and culture. It doesn’t propose any policy solutions to the problems of mass incarceration or extralegal detention. I hope it shows some of the reasons why these problems are so deep and so difficult. Will it piss anybody off? I don’t mind.

What alternative title would you give the book?

My original title was The Meaning of Solitude, but the book expanded to address a broader range of questions, and now that’s the title of one chapter about the history of disciplinary isolation from early monasticism through the first reformatories and penitentiaries. I think The Prison and the American Imagination is all right, maybe a little too grandiose. I was glad to avoid using a colon.

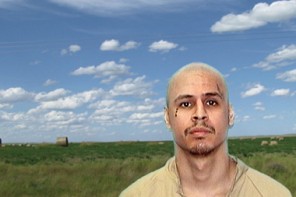

How do you feel about the cover?

I love it. The image is by a contemporary artist named James Casebere. He builds tabletop models and photographs them with gorgeous, ghostly lighting effects. He has made several images based on real prisons, including Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, one of the most important institutions for my research. This particular picture called “Asylum” seems to communicate the mysticism associated with solitude: you can see how religious traditions and penal policy come together in the image of the cell as a space of redemption. One of the best parts of working on the book was getting to know Jim. He read the work in progress, and he was terrifically warm and generous. I visited his studio in Brooklyn, saw the models he’s been working with lately, and learned how a great visual artists handles the ideas that I usually encounter through the medium of language.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written?

There are hundreds. I might start with Bartleby, by Herman Melville. The title character is one of my heroes because he steadily refuses to submit to the kind of humanizing redemption that his boss offers him, even though his refusal leaves him abandoned to a fate of ghostly inhumanity. He dies in a New York prison called The Tombs.

What’s your next book?

I’m working on something called The Oracle and the Curse: A Poetics of Justice, 1765-1865. It’s about how judges and offenders alike appealed to a higher law—divine, natural, or national—in the postrevolutionary age of print media, secularity, and popular sovereignty. As John Brown wrote on the day of his execution, “The crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”