The following is the first episode from Mark Dery’s nonfiction novella, How I Lost One Leper Messiah, and Gained Another. Read every Friday for the next installment or read them all here. —Ed.

As Jesus was on his way, the crowds almost crushed him. And a woman was there who had been subject to bleeding for twelve years, but no one could heal her. She came up behind him and touched the edge of his cloak, and immediately her bleeding stopped. “Who touched me?” Jesus asked. When they all denied it, Peter said, “Master, the people are crowding and pressing against you.” But Jesus said, “Someone touched me; I know that power has gone out from me.” —Luke, 8:42-46

●

A teenage girl is crying, sobbing inconsolably, her face a tear-streaked mask of sweet anguish. She’s English, dressed in schoolboy drag: a white dress shirt and blazer, topped off with the regulation necktie. Pinned to her jacket is a photo button of David Bowie in character as Ziggy Stardust. She exhibits all the emotional stigmata of Ziggymania, a hormonally fueled religious hysteria that convulsed Anglo-American teen culture from 1972 until 1974, if not later.

We’re watching her in a 1973 report on the Bowie phenomenon by the BBC news program Nationwide, uploaded to YouTube. “They said ‘e was comin’ ‘round the back! I’ve been waiting for ages to see ‘im,” she wails, agonized at missing the star’s limousine arrive. “Why’re you so upset?” a bemused interviewer asks, across a generational chasm. She looks up, incredulous at the man’s inability to grasp the obvious: “He’s smashing!” Another girl crowds into the frame, as radiantly happy as her friend is distraught. “I kissed his hand!” she gasps, in the grip of some mystical eros. “I kissed his hand! I went (mimes kissing Bowie’s hand); Oh, he’s lovely!”

●

It pleased our Lord, one day that I was in prayer, to show me His Hands, and His Hands only. The beauty of them was so great, that no language can describe it. […] You will think…that it required no great courage to look upon Hands…so beautiful. But so beautiful are glorified bodies, that the glory which surrounds them renders those who see that which is so supernatural and beautiful beside themselves.

— Saint Teresa of Ávila, “Chapter XXVIII: Visions of the Sacred Humanity, and of the Glorified Bodies,” from The Life of St. Teresa of Jesus, of the Order of Our Lady of Carmel

●

Ziggy Stardust, for anyone who wasn’t a teenager in the seventies, is the protagonist of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, Bowie’s 1972 concept album about a Martian prophet of “soul love” who touches down on a doomed Earth.

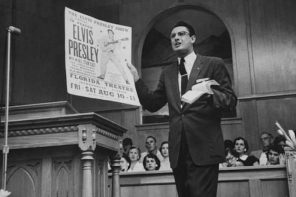

Proclaiming an astro-hippie gospel of transcendence through free love (“let all the children boogie,” unquote), Ziggy seizes on rock stardom as the most effective media pulpit for his message. Not content with mere celebrity, he imagines himself a “leper messiah.” But, like too many telegenic holy men, he ends up seduced by his own Cult of Personality: “making love with his ego / Ziggy sucked up into his mind” (“Ziggy Stardust”). In the Ziggy outtake “Sweet Head,” he sings, “Your faith in me can last / Besides, I’m known to lay you, one and all,” then tosses off a line calculated to outrage: “Till there was rock, you only had God.”

In the end, he’s murdered by his crazed fans, torn limb from limb onstage. His jealous backing band, The Spiders from Mars—who had “bitched about his fans” and toyed with Golgotha-friendly fantasies of “crush[ing] his sweet hands”—wash their hands, Pontius Pilate-like, of the whole sordid business: “When the kids had killed the man I had to break up the band.”

In concert, Bowie became Ziggy, introducing himself and his band as “Ziggy and the Spiders.” Forehead emblazoned with a gilded moon, hair dyed drop-dead red and spiked into a Kabuki frightwig, he was a vision of posthuman beauty, with a face like Garbo’s death mask and a leer on loan from Alex, the ultra-violent punk in A Clockwork Orange. And the costume changes—a whole clothes rack’s-worth of them, each more jaw-dropping than the last: sci-fi samurai in a tear-away kimono; camp Flash Gordon in a skin-tight jumpsuit; gay-pride sumo wrestler in a sequined jockstrap; Surrealist burlesque dancer shimmying in a man-bra made of glitter-skinned mannequin hands.

Freeze-framed in the eerie pulsations of a strobe, with the raunchy proto-punk of the Spiders squalling behind him, Bowie—Ziggy?—seemed truly Not of This World, especially to teenagers trapped in the have-a-nice-daymare of ’70s suburbia. He was a spiked cocktail of ladyboy vulnerability and George Grosz grotesque, the Frankensteinian spookiness of his shaved eyebrows and morgue-slab pallor clashing with his androgynous physique and feline grace. Even his weirdly mismatched eyes—the result of a boyhood fistfight that left one pupil permanently dilated and different-colored—marked him as a resident alien.

“It was quite scary to see someone on stage who did look like an alien,” recalled a Bowie fan named Bernard. “I remember I got really confused and at one point I really did think he was something alien…in all that Ziggy get-up, he was such an awe-inspiring figure.”

At the height of Ziggymania, Bowie ended each concert with Ziggy’s swansong, “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide.” The song builds, cresting in a hymnlike refrain worthy of a Broadway curtain-closer: “Gimme your hands ‘cause you’re wonderful / Gimme your hands ‘cause you’re wonderful.” Peaking, the song crashes with Ziggy’s last words, caught at the moment his orgasmic cry turns into an agonized wail, as his fans rip him to shreds: “Oh gimme your hands!”

By all accounts, Bowie’s then-wife Angie dreamed up the gimmick of having Bowie extend a pleading hand toward the crowd as the song crescendoed. Soon enough, the gimme-your-hands shtick was as formalized as the laying-on of hands at a faith-healing revival—a spotlit rite of communion between a worshipful crowd, desperate to touch the “leper messiah” (“Ziggy Stardust”), and a star who flirted with delusions of messianic grandeur.

In truth, Bowie was haunted by the fear that he would be rock’s first martyr, a blood sacrifice to celebrity culture. He exorcized his fear (even as he indulged his Saint Sebastian complex) before a howling crowd, in Ziggy’s passion play.

Offstage, his calculated blurring of the boundary between media myth and private self brought him perilously close to living out the Ziggy-esque martyrdom of his paranoid fantasies.

Part 2: At 14, the author, stranded in 1974 suburbia, has his born-again Christian brain short-circuited by the gender-bent but heart-stoppingly beautiful Ziggy.