“I’m unbelievably bored writing about Judaism as a journalist,” author Gordon Haber said during a recent conversation with RD. When Haber compiled Uggs for Gaza And Other Stories, his debut short story collection, he didn’t set out to tackle the American male Jewish experience. But the stories, which tackle questions of ethnicity, identity, masculinity and otherness, all feature non-practicing American Jewish men.

“I’ve been focusing on Judaism for so long. And then when I put the collection together, I was like ‘Oh god, every single protagonist is male and Jewish, so I guess I’m interested in that.’”

The characters in the collection, according to Haber, are “the grown children of Bellow and Roth,” struggling to earn a living, live authentically and find their place in unfamiliar surroundings.

UGGs for Gaza

Gordon Haber

Dutch Kills Press

March 2017

In the title story, a young man, new to Los Angeles, tries to impress a woman at a party by telling her he runs a charity that donates shoes to Palestinians. He comes up with the idea on the fly, but soon finds himself tackling the logistics of collecting, packaging and actually trying to ship dozens of pairs of Uggs to the Gaza Strip. In other stories, protagonists attempt to find their way in Poland, England and France.

Haber, who also writes criticism and journalism, is the co-founder of e-book publisher Dutch Kills Press, which published Uggs for Gaza in March. RD spoke with him to learn more about the questions of ethnicity posed by the collection and what it means to be Jewish in America today. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This collection, in many ways, is about the American male Jewish experience. Is it essentially a memoir in pieces?

None of it’s strictly autobiographical, but one of the things that’s autobiographical is the feeling of alienation; of being Jewish when you’re not in New York. Because some of the things I experienced in different countries, like these characters did, where, when you leave your enclaves, like New York and L.A., and you go to places like London or Warsaw, it’s still kind of weird to be Jewish. It’s just not that big of a deal in a lot of cities in America. But when you go abroad, you realize it’s a different thing to be.

Right. Like in “The Real Story of Nigel Embo,” the protagonist offhandedly says he won’t be going home for the Christmas holiday because he’s Jewish, and the room goes silent.

Yeah, they don’t know how to deal with it. Like when I lived in Poland for a year, and I found that that would happen all the time. You never knew how people would react to the mere fact of being Jewish. Some people didn’t give a shit, some people were hostile. But it’s the kind of thing where you just never knew what people would say to you. There were times when I mentioned it and you could feel a chill in the room. Not like I expected a pogrom, but you realize there’s a certain element of different-ness, of otherness, that still exists. So that’s definitely a theme in a lot of stories.

That’s something that’s particular to the American Jewish experience for you?

I don’t know if it’s American, but maybe it is, in terms of, I think, my expectations for [how] Jewish people behave. My experience of America is fairly limited. I know New York and I know L.A. I wouldn’t be able to discuss what the Jewish community in Nebraska feels like. But in my experience I’ve found we’re much more comfortable in our own skin than other communities. It says something good about America but I don’t know what.

One thing that was interesting to me in these stories is how the American Jewish experience changes over generations. In “His Grandmother’s Memory,” the protagonist’s grandmother, who left Poland right before the Holocaust, dies. He is taken over by her spirit and can suddenly speak Polish and Yiddish. Is there a shift in American Jewish identity as we get to a point where the last of the Holocaust survivors are dying or have died, and there are fewer connections to the people who fled Europe?

That’s probably the most Jewish story, obviously. I wasn’t really conscious about it when I was writing, but after I was like, oh this is clearly a metaphor for what we owe previous generations. How much are we supposed to remember, and how much are we allowed to forget? There’s all these burdens that the past places on you.

But the larger question is about the community and the distance from disaster, and like anything else it fades with time. My grandparents were not [Holocaust] survivors, they emigrated in the 20s, but my grandfather’s entire family, except for my grandfather’s brother, was murdered. So I had a very direct connection to that community, and to that country. But I’m an older dad and I have a six-year-old son, and he’s going to have a much different relationship to that part of history than I will, which may not necessarily be a bad thing.

In the story about Nigel Embo, one of the characters comments that the protagonist can’t be racist because he’s Jewish. I’ve heard this said before—white Jewish men claiming they can’t be prejudiced because of their history.

I’m looking at my grandfather’s diploma from dental school, in Polish, on the wall right now. And I’ve been to his hometown. He had five siblings, and four of them were murdered, so how can I not forget that? But the idea of saying that that applies to how I’m living right now would be ludicrous. There’re a lot of concerns that all minorities have in America right now, which I think are valid, but the idea that I understand what true oppression feels like or that I understand what it’s like to face bigotry every day of my life is ridiculous.

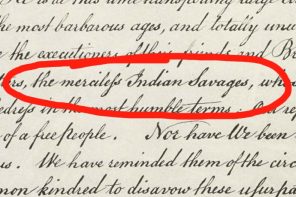

A lot of these questions of memory and responsibility resonate differently since the election.

One of the things that drives me crazy are Jewish Trump supporters, because they have no memory. In a way that’s like, the one thing we want to remember is what it’s like to be so vulnerable in times of disaster, and they have completely forgotten it. And all the rhetoric we’re seeing now against Muslims could very easily be swapped out against Jews or Italians before the war. It’s really infuriating to see people who forget that so quickly. It’s like, when they talk about the Judeo-Christian ethic, all they’re saying is “not Muslim.” Basically all the ethics we like in Judaism and Christianity are in Islam, too.

In the title story, “Uggs for Gaza,” this guy moves to L.A. and because he’s Jewish, people assume he has an interest in the Middle East, but he has no idea what’s going on. If you’re a member of a non-dominant cultural group it’s often assumed that you see your identity in a political way.

I wasn’t overtly saying this, but the character gets forced into some sort of political role anyway. I was more interested in seeing him trapped in a situation through his own mistake. He’s just trying to get laid, and the whole thing snowballs on him. A lot of people are offended by that title. It’s like when you mention Israel⎯people get nervous just when you mention certain words.

But I don’t want to be disingenuous. I purposefully chose that title because I wanted people to remember it.

The idea for the story itself came about when I was driving around L.A. with my wife (though we weren’t married yet) and one of our friends, and we were joking about what would make the most useless non-profits. Literacy for Lobsters was one of them. And Uggs for Gaza. And then I wondered, how would you actually get Uggs to Gaza? And I actually started to do research on how to ship to the Gaza Strip.