Revelations abound. Hurricanes, earthquakes, and wildfires crowd the news, alongside genocide, terrorism, and rogue state tests of intercontinental missiles and the nuclear warheads with which to arm them. Headlines offer either a string of senseless horrors or an array of signs and warnings.

As catastrophe births desire for dramatic change, so, too, the chaos of existence prompts in the human mind a search for patterns, a rage for order. Thus, days like these are not merely ripe for hopeful prediction of the world’s end, they are ripe, too, with particularly striking demonstrations of how the religious imagination works and of the desire of some religious individuals (as well as journalists and scholars of religion) to dismiss such thinking as somehow less than really religious.

Some, like Ed Stetzer, executive director of Wheaton College’s Billy Graham Center for Evangelism, quoted in the Washington Post, polices Christian orthodoxy by insisting “There’s no such thing as a Christian numerologist,” despite myriad examples of such, from ancient times to the present.

As Stetzer virtually excommunicates Christians with whom he disagrees, experts employed by watchdog groups perform another kind of excommunication, dismissing fellow citizens as either duped victims or predatory leaders of so-called “doomsday cults.”

A recent piece by the Southern Poverty Law Center, an organization intent on separating dangerous (and therefore false) religion from kindly (and therefore real) religion, describes one such community as espousing “radical views… toxic… lead[ing] unsuspecting followers down a funnel of despair, which perpetuates fear, paranoia and extremism.”

As academics, we too engage in this practice, policing the boundaries between supposedly “mainstream” religion and “new religious movements,” a euphemism chosen to replace the derogatory label of “cult,” the category it nonetheless reiterates.

Many such supposedly non-Christian, extremist, “new religious” thinkers are investing hope in this coming weekend as a banner date for the apocalypse. Such speculation involves hope because the end of the world is never quite that—the end. Apocalyptic narratives focus on the end of certain social orders, political realities, ways of being. The end times is generally just a point in time, a reset on the status quo, a reorienting of the arc of history. Such expectations may involve massacre and cataclysm, cities in ruin, cats laying down with dogs, but they do not represent the end of human history, merely a transition.

As has been reported by both mainstream and tabloid media, a variety of religious thinkers are focused on Saturday the 23rd as one such transition. (There is some debate about when, precisely, that date will start, with some insisting on sundown Friday—Rosh Hashanah’s end—and some pointing out that the only time zone to worry about is Jerusalem’s, meaning that a global cataclysm at dawn on the 23rd would chip ten good hours off of Los Angeles’s Friday).

As true in ancient Babylonia as it is today, the creativity of cooptation and the capacious approach to claim-making is how religious thought happens.

For some, this weekend’s apocalypse involves a planet called Nibiru, but for others, notably various Christian communities around the world, this weekend marks the beginning of the Tribulation, a profoundly disastrous time of suffering and mass death that precedes the return of Christ. And some claim that the horrors of such trials can be avoided if (and only if) the truly faithful find their way to the ancient Nabatean capital of Petra, the Rose City, Jordan’s most famous archaeological site.

“Petra is the one-and-only place of safety” for the next three and a half years of Tribulation, declares the Petra—Place of Safety website, which identifies Petra as “the singular ‘place prepared for her in the wilderness’ for the Woman of the End Time (Revelation 12:14).” This figure, identified as “all the Holy Spirit Sealed believers in the Messiah over the course of all history,” isn’t an individual woman, but a collective “Bride of Messiah,” meaning 144,000 true believers, only just over 2,000 of whom are active followers of the related Facebook page.

The figure behind this specific prediction is one Jane E. Lythgoe, a religious thinker and entrepreneur who identifies as “Brit-Kiwi-American. Messianic Believer,” with interests in ancient Hebrew pronunciation, tracking the Lost Tribes, and mapping the madness of the modern world onto a plan laid out in scripture.

“Over the last 10 years I’ve just independently studied the Bible and Petra myself, and come to my own conclusion,” she explains. “Over this time I have collected a large amount of what I believe to be solid Biblical, historical, cultural, archaeological, geological, and astronomical evidence, that Petra is the Place of Safety.” (A video condensing those ten years of research to ten minutes can be found here.)

Lythgoe’s particular message is inimitable, but her approach is far from unique. Indeed, she is representative not only of a broad swath of end-timers interpreting everything around them (from news reports to movies to the shapes of flowers to advertisements for athletic shoes) but, in the frenzy of such urgency, she makes visible the dynamic of eclectic and omnivorous borrowing and reframing that marks the religious imagination. As true in ancient Babylonia as it is today, the creativity of cooptation and the capacious approach to claim-making is how religious thought happens. In our digital age, this is both easier to see and more wildly global in its influences and reach. Lythgoe speaks to the citizens of the world.

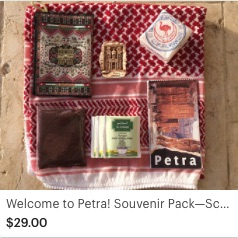

An offering from Lythgoe’s Etsy page.

From her refuge near the ancient clefts in the rocks of Petra, Lythgoe communicates her warning through memes and references to pop culture alongside traditional recourse to scripture. Through Pinterest and an Etsy store she sells “Luxury Earth-friendly Biblical souvenir jewelry” from “organic, fair-trade and/or recycled materials” with patterns such as the Hebrew name of God and the façade of Petra’s Treasury building. As with the recent election, memes are a central form here, part of a broader strategy of claiming clues from pieces of information already in plain sight. Imposing upon sources the data one seeks to find, Lythgoe finds hidden meaning in blockbusters like The Purge: Election Year and Wonder Woman, as well as archaeology, politics, and exegesis.

Still from The Simpsons.

“This is what a doomsday prepper really looks like,” reads a meme of a person at prayer over a clutched bible, while another informs us that the Hollywood comedy Evan Almighty featured a great flood on September 22nd, or, more obliquely, that an episode of The Simpsons showed the series’ most notably Christian character, Ned Flanders, check an electrical meter which read “92200.”

Did you ever notice that the job of the Rock in the disaster film San Andreas was primarily to airlift women, just as “the woman” that is the true community of God will (possibly) be airlifted this coming Friday/Saturday? Lythgoe notices for you, memes it, repeats it, and posts in on multiple platforms for you to find the signs (which you, in turn, can then share). “Keep Calm and Flee to Petra” reads one meme, offering a take on a recently re-faddish phrase. A brightly-colored status update announces, “If you don’t see my posting any more it might be because I’ve been sealed into Petra.”

Lythgoe also looks for omens where the ancients looked, “in sun and moon and stars” (Luke 21:25), calculating correspondences between calendars Hebrew and Gregorian as well as astrological charts. As for signs in the earth, Lythgoe takes recourse to satellite photography and Google maps, able to articulate a claim that the eagle of Revelation can be seen in the topography of Jordan itself.

Critical of Trump’s lifestyle, Lythgoe identifies this “deceiver” as a secret Assyrian, finds unholy geometry in his hairstyle, and gives him the not-so-subtle Tribulation title “Beastrump.” While barbed, such politics are ultimately non-partisan. Lythgoe was similarly critical of Clinton. It is earthly power itself that’s seen as corrupt; Trump just offers a spectacularly rich example to pair with scriptural critiques.

So is this Christian thought? Is this religion? Decades ago, at the peak of the move to stigmatize contemporary religious claims under the derogatory label of “cult,” scholars spoke of the so-called “cultic milieu,” understood as a kind of shadowy underworld of kooky theories, conspiracy lore, and revamped tales from old times. The king sleeping under the mountain became a UFO under the mountain.

While used as a tool to explain very real religious claims, the larger purpose of this theory was to protect what scholars and much of the public considered to be “real” or “good” religion, the stuff of “mainstream denominations” or the reified Big Five “World Religions” imagined as monolithic structures with clear orthodoxy (and standardized ethics). The “cultic milieu” was not our milieu, such arguments went.

But it is, and Lythgoe’s work makes this strikingly evident: we live in her world, and while we may not agree with her calculations, her faith both in individual rationality (born of the Reformation and reiterated by the Founders of America) and in faith itself (her willingness—even desire—to foreground belief and work backwards at rationalizing) are basic dynamics of thinking within those communities we categorize explicitly as “religious” as well as a few others, which we might prefer to label “secular”—like law or politics.

To dismiss Lythgoe’s thinking as “unchristian” is a theological move, but to dismiss it as somehow representative of “cult” thinking rather than religious thinking more broadly acts as a parallel move—one of an invested believer seeking to mark and protect the boundaries around acceptable orthodoxy.