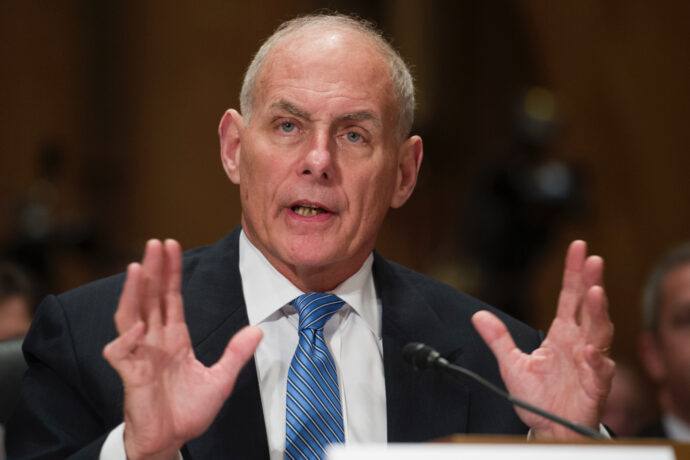

When General Kelly noted this week that Robert E. Lee was an honorable man—and added that we could have avoided the war if people had been willing to compromise—he was rightly criticized.

“Honorable” is not apt label for a slaveholding traitor, as many pointed out, and compromising on whether some people can own other people is morally repugnant. And of course the North and the South did actually compromise repeatedly.

Kelly’s opinion shocked many, but for others it invoked a familiar framework about the Civil War that protects white supremacy and which is at the core of one of the most influential strands of today’s evangelicalism: the strand that help elect Donald Trump. On twitter, as part of the #emptythepews hashtag, ex-evangelical @toriglass wrote, “to be honest, evangelicals never stopped debating whether slavery was actually bad.”

She’s right.

This framework asserts that the Civil War was not primarily about slavery, that slavery itself was not nearly as bad as we are led to believe (in fact it was a “positive good” in that it exposed Africans to the Gospel and to a “biblical family”). The war was framed as a theological conflict in which Southern culture was an expression of a Godly civilization battling against a materialistic “humanistic” one.

These were not “fringe views” in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, throughout which almost all white American Christians supported slavery and understood it as completely compatible with the Bible (the exception was the small but growing strand of abolitionists many of whom were also evangelical). One important proponent of the biblical defense of slavery, and the explicit criticism of the value of social equality, was nineteenth-century Southern Presbyterian theologian, R.L Dabney. Dabney wrote extensively also against women’s rights and universal suffrage.

By the time Dabney’s work was revived in the twentieth century by R.J. Rushdoony (about whom I wrote here), the explicit defense of slavery had moved to the fringes in favor of vigorous defense of segregation—but its racist undercurrents persisted.

By the end of the twentieth century, theologian Doug Wilson repeated Dabney’s and Rushdoony’s proslavery arguments in his book Southern Slavery as It Was (co-authored with League of the South Board member Steve Wilkins). And home school activist (son of the Constitution Party’s founder) Doug Phillips reprinted some of Dabney’s work under the affectionate title Robert Lewis Dabney: The Prophet Speaks. Dabney and those who continue to embrace his work continue to object to notions of social equality—whether they be racial, ethnic, gender or other kinds—as explicitly unbiblical.

Wilson and Phillips may be obscure names to some, but Wilson travels in circles with the most prominent of Reformed Christian leaders (here is an example in which he appears with well-known theologian and popular John Piper). Back in 2009 historian Molly Worthen noted Wilson’s transition from the far right fringe into the mainstream of American Evangelicalism. And until Doug Phillips lost his business and his ministry (in a scandal surrounding his inappropriate interactions with his nanny in 2014) he was one of the most important home school leaders in the country.

To be fair it is difficult to try to use the Bible as a moral compass, given its general endorsement of slavery. But evangelicals influenced by this Southern Presbyterianism have sought to carefully lay out the limits of the places in which the text permits slavery—claiming that most of biblical slavery was temporary as a result of debt or war, or that it was “voluntary.” If you dig deep in their work you find that only “pagans” can be forced into perpetual slavery—though of course for them that’s any group not understood as Christian on their rather narrow terms.

The work of Wilson, Rushdoony, Phillips, and others that built on this apologia for the Confederacy, made its way into Christian School and Christian home school curricula, ensuring that the perspective was widely disseminated, and moving it again from the fringes of evangelicalism to the center of a vibrant and growing strand that has now helped elect a President.

A generation of evangelical kids in Christian schools and home schools were taught aspects of this narrative about the Civil War and America slavery. It went mainstream with David Barton, Glenn Beck and the rise of the Tea Party, and has now found a home in the West Wing with V.P. Mike Pence and numerous members of the cabinet. But while you have to dig deep to find the really ugly stuff, much of it goes no deeper than “there were good people on both sides.” The rest often remains unspoken.

I’m not suggesting that evangelicals are solely responsible for the prevalence of this wrong-headed view of history; you should watch this video of the role of the Daughters of the Confederacy in promulgating it in monuments and textbooks. Moreover, there were always strands of evangelicalism that resisted this view and continue to do so.

But these days, evangelicalism is silencing criticism within its own ranks as part of its Faustian bargain with Donald Trump, as some 80% of them voted for him. And over the last fifty years obscure factions within the evangelical tradition laid the groundwork for the mainstreaming of what were previously fringe views about race, about the South, and about the civil War.

That evangelicalism is deeply implicated in white supremacy gets clearer by the day.