The sudden birth and development of the #NEVERAGAIN movement, led by students who survived the February 14th school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, has been startling, to say the least. There’s something categorically different about these teenagers, beyond their exceptional clarity, directness and strength. They’re willing to say what the adults can’t: that their own lives are less important to the political system than fetishized guns.

You might wonder if that isn’t exactly what adults have been saying, at least since the slaughter of first-graders in Newtown, Connecticut.

But there’s a crucial distinction here. The Parkland Students can say it from within. They’re able to name the grief and outrage of victims in a way that hasn’t been possible before. Even the most articulate first-grader is still a first-grader, while parents of the dead are dismissed as undone by their grief. The Parkland students, by contrast, have the credibility of somebody who’s been shot at, the pissed-off edge of those who have lost loved ones, and the ability to speak their minds, bluntly.

It’s the same with the #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter movements. With the aid of social media, they’ve been able to name the suffering, to make it visible—and then to demand redress for their grievances. You can’t watch Philando Castile die before your eyes, or experience the terror and suffering of children in a school under siege and deny the wrongness of what’s happening before your eyes. To witness the grief with any kind of life in your soul requires hearing the cries for relief in a new and different way.

Then too, these movements—for gun control, or for racial or sexual justice—speak in a fundamentally new way. Ordinary people are standing up and speaking for themselves, not relying on surrogates or political parties to work on their behalf. The Parkland kids have been called pawns in an attack on Second Amendment rights, but they’re not liberals. They’re victims who refuse to play the role. There’s a strength in them not seen in recent years. It’s present in the outpouring of joy at the release of the Black Panther movie too, and in the willingness of many women to speak openly about the sexual abuse they have experienced.

Things are changing, permanently. Yes, the people who would like to hold back the tide are in charge, for now. But they’ve lost all legitimacy, and what we know about illegitimate regimes is that they don’t last always.

It’s inspirational, amazing and not a little unnerving to watch as people claim power one bold step at a time. There’s something spiritual in it. If you’ll forgive a bit of Bible-thumping, as Jesus says in the gospel of Mark, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news.” This needs to be heard less as eschatology—the end of the world is not upon us—but as ontology; the world is changing around us, and we in it.

The idea that God is bringing something new into the world is like an electrical current running through the scriptures of the Abrahamic faiths. This is nowhere more apparent than in the book of Exodus, where the Israelites are so beaten down by their slavemasters that they don’t even know how to cry out properly. God (the LORD, as he styles himself) hears their groaning, and from that smallest of beginnings builds an entirely new society. It’s striking to think that we may be seeing something like that happening before our eyes, whether through divine initiative or human resilience in the face of violence. The children are groaning, and now something new and surprising is rising from the death that everywhere threatens to overwhelm us. It’s not clear yet what that will be, but it’s powerful enough to cause Pres. Trump to offer up immediate action, however modest.

Whatever this newness is, however, it’s in constant danger. A smear campaign against the young leaders has already begun. Social changes arising from the margins are always tenuous and subject to destruction. It is the price of stepping to those in power.

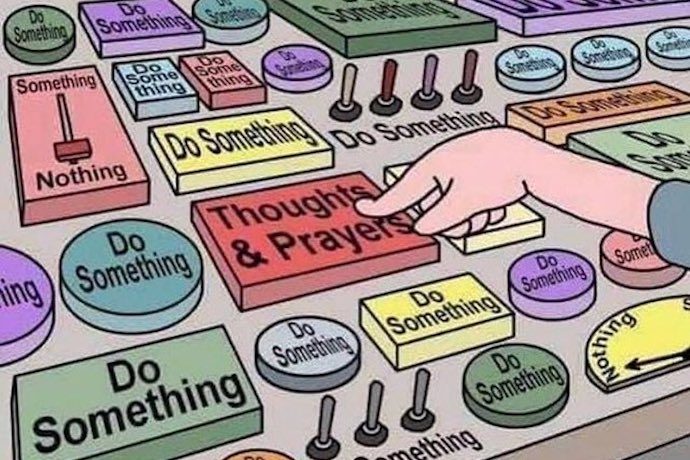

Whenever we talk about mass murder in the U.S.—which is often—eventually the conversation comes around to the perceived dichotomy between “thoughts and prayers” and action. This time is like any other. Timothy Egan recently wrote in the Atlantic that:

Since 1995, there have been more than 4,000 instances of someone rising in Congress to express “thoughts and prayers.” And since that time, about seven children or teenagers have been killed, on average, every day by guns.

That’s something like 8,000 days, or about 56,000 children killed; roughly 14 children murdered for every thought or prayer offered in Congress. It’s enough to make the terminally smug proclaim prayer doesn’t work, and can you blame them?

But know this: In Christian terms (which is the context for nearly all of these prayers), among many other things, prayer is meant to open humanity to the workings of God to bring about the kingdom. To the extent that humans can be said to help that project, the work is nurtured by the practice of prayer. Through prayer, Christians listen for God, and open their hearts to solidarity with those whom God is for. Prayer sparks the transformation of our ontology, and announces the end of the process even as it begins.

Knowing this helps us to understand what’s wrong with the constant refrain. The problem isn’t simply that “thoughts and prayers” don’t lead to action, nor that generally they’re offered insincerely or cynically. Sometimes they are, to be sure, but for the most part they seem to be given with great sincerity and emptiness.

And there’s the rub. Thoughts that don’t lead to new things aren’t very deep thoughts. Prayers that don’t change those who worship aren’t really prayers. Giving thought to the problems of gun control, police killing, sexual violence, is worthless without thinking about how things could be different. Praying for victims of violence and injustice without being changed by their grief is shit.

In sum, offering thoughts and prayers without listening for the new world that is coming into being is worse than useless. It’s pathetic, an empty shell of faith, like a firework launched high into the sky only to fall back to earth unconsummated. The fire of new things is coming, and the old duds are passing away, soon to be forgotten.

There need not be any pre-appointed end to history to know when you’re on the wrong side of it. And those who side with the violent and the oppressor are most definitely on the wrong side of history. That is my faith at least, not that some benevolent sky daddy is going to fix everything for us. Give me liberty or give me death! shouted Patrick Henry. Give me thoughts that bring new life to the world and prayers that open hearts to welcome change, say I, because we’ve had more than enough death to go around.