Saturday’s surge of Occupy actions around the globe could be a turning point, a hinge moment, as occupiers in over a hundred American cities feel the power of worldwide welcome and affirmation. There is obviously more to be felt and said about this than any journalistic treatment could hope to engage; one senses in many recent commentaries the strain of needing to say more and not quite having the words. Over the course of a couple of days, four regular RD contributors, moderated by Senior Editor Sarah Posner, shared their own thoughts about a movement that remains fluid and thrilling—and quite literally indescribable.

Anthea, Last week you published a wonderful remembrance of the life of the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, in which you wrote, “his wasn’t a weak, wimpy faith, but a fiery righteousness that seared all untruths in its path.” That seems to capture the subversive fervor that so far has been the image of OWS.

But video footage from Occupy Atlanta, in which the group is shown rejecting an offer from civil rights legend and Congressman John Lewis to speak, depicts instead a sacralizing of process over just about everything else—history, respect, political savvy, common decency—a kind of blasphemy, if you will. Sure, this is one Occupy group, and doesn’t represent all of them, but do you think the devotion to the process of decision-making by consensus can undermine the spontaneity and potency of spiritual inspiration?

AB: I happened to see the clip of the #Occupy Atlanta Incident over the weekend, and I spent a considerable hour in my Twitter timeline ranting about how John Lewis had been treated. Since then, someone on Twitter tried to engage me about how it was all a “mistake” and [pointing out] that Lewis had been invited back. Joan Walsh wrote a piece in Salon explaining why it was, despite appearances, appropriate.

I’m still ticked about it, and here’s why: whatever the extenuating circumstances were (Lewis is a congressman or We have a process) it doesn’t take into account how Lewis could have shared and inspired, through his own experience, what the Occupy Atlanta protesters could face. The moment you get pepper-sprayed, hosed down, bitten by dogs, etc., is the moment you are going to decide whether you’re all in or all out. That moment of enduring physical or psychological pain is an inspirational moment, whether you believe or not. That’s what Civil Rights protesters like Lewis had: inspiration. Lewis’ testimony is even more potent for the fact that he’s been harassed and called n*gger, not just during the Civil Rights Movement, but in the last two years by Tea Partiers.

I doubt many if any of the Occupy Atlanta protesters have experienced anything like that. By becoming slaves to the “process” rather than accepting inspiration, the majority behaved like the corporate scions they hope to overthrow. Not much inspiration happening when the process mimics a board meeting.

What my Fred Shuttlesworth piece showed was that there wasn’t consensus in the Civil Rights Movement either. Lots of people in the movement disagreed about violence vs. nonviolence, civil disobedience vs. abiding by the law, etc. What may undermine the Occupy movement is a sense that they must have complete consensus. Not going to happen.

The most troubling thing to me is that the tape from Occupy Atlanta looked like the Borg of Star Trek. Movements don’t have a hive mind. The Occupy folks need to understand how to hold the constituencies together—and especially the gender, ethnic, and historical elements that are prone to gravitate to this movement. Folks like myself who want to participate and help will not tolerate the kind of disrespect of a noted Civil Rights leader, even if it wasn’t deliberate.

Still, I am 100% down with the Occupy movement. Every movement will have its growing pains, and this was one of them. There have been other racial incidents, including here in Philadelphia. I hope these growing pains will not hamper the momentum of a much-needed counterweight to the 1%.

Nathan, you’ve been in New York covering Occupy Wall Street from the beginning, during which time a group called Protest Chaplains has been on the scene; religious groups showed up for the big march on October 6; and the following day’s Kol Nidre service was held in Zuccotti Park and has since developed into Occupy Judaism, which describes itself as “Radical Jewish Direct Action in support of Occupy Wall Street.” As far as I can tell from a distance, these phenomena have drawn on familiar but enduring biblical themes, including the nature of sin, atonement, and justice, and look to the prophet Isaiah or the teachings of Jesus in Matthew 25.

Are these religious actions more essential to religion than to Occupy Wall Street? In other words, does OWS need them to succeed, or did these activists need OWS in order to reimagine the role of their respective religious traditions in contemporary political activism?

NS: Actually, the very first thing I noticed when I arrived at Wall Street on September 17 was the Protest Chaplains, in white robes, singing across the street from Trinity Church. (I had been in touch with them the previous week over Twitter.) Performance artist Reverend Billy helped convene the first big crowd that day with a sermon. [So] they had a strong and visible presence the first day, but by that night they were gone, and—aside from a few colorful anecdotes, like when an organizer named Ted announced he was going to drive a nail through his hand in solidarity with Jesus and Troy Davis—the first couple of weeks of the occupation were ostensibly pretty religion-less.

Of course, in the rupture of the ordinary that characterized that period, everything felt in some sense religious. The trappings of ordinary religion (rituals, structured prayers, etc.) felt pretty unnecessary, since every moment seemed already so charged with a secret extremity and transcendence—secret, because the rest of the world hadn’t yet become aware of what powerful stuff was happening down there.

Now, as the Occupy phenomenon grows and spreads, I think there is more space and place for these trappings. It needs structure, it needs regular practice, it needs to consciously recover its endemic transcendence. As if heeding the call, religious groups are starting to take note and offer their services. Like the unions and like the political groups, it seems like religious organizations are now starting to take their cue from OWS about where political activism is headed. But, like those others, traditional religious institutions will probably only be able to go so far in joining the bandwagon of a movement that is self-consciously non-hierarchical, revolutionary, and disruptive. Unless they succeed in co-opting it.

Nathan brings up the trappings of ordinary religion, the rituals, ceremonies, and structure that he argues are now needed in the Occupy movement. I was interested that he brings up the idea of religious structure, because one thing people frequently ask me, in the context of my reporting on the religious right, is, “where is the church for progressives?”

In other words, they look at conservative megachurches and televangelism and see no countervailing structure that is both religious and political.

Elizabeth, can Occupy be the megachurch of the left? Should it be?

ED: The megachurch movement, which comes directly out of mass media culture, separates people into consumers of messages that prompt unreflective behavior. Where reflection or questioning are the rule, they fall flat. This is the cultural domain of progressive churches.

Certainly, digital culture has allowed for the aggregation of conversations among clusters of progressives, and that has extended the conversation somewhat into the wider culture. But, as we saw in the #OccupyAtlanta debacle with Rep. Lewis, the interpersonal quality of progressive Christianity limits the extent to which religious progressives are ever going to develop structures and processes that allow for anything like a megachurch to emerge.

So, no, I can’t imagine that OWS has the potential to generate a megachurch-type ethos among religious progressives, nor do I think it should.

The “structures” that Nathan talks about—rituals, prayers, and other sacramental practices—are not institutionalizing structures per se, but the stuff of both personal and communal spiritual practice. The Protest Chaplains and other religious progressives (or not, theoretically) who minister to the protesters reinforce religious interpretations of the protests, providing a narrative thread that goes beyond the initial narrative of civil disobedience, which is what Martin Luther King Jr. and Gandhi did—they recast civil disobedience as spiritual disobedience, allowing for the emergence of movements that were far more than political in their significance.

In this sense, the religious practices—preaching, prayer, scriptural symbols like the now-ubiquitous golden calf, the offering of hospitality, food, and so on—are the practical lexicon of what I would argue is a much richer, much more provocative and challenging narrative of the movement.

A couple weeks ago when I visited the #OccupyStLouis encampment on a Sunday morning, I talked with a small group of demonstrators about the intersection of faith and money and fair treatment of workers. Most of them hadn’t given it any thought.

“Maybe we should occupy the churches,” one protester half-joked as we talked. It’s a notion I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. What would it mean for God’s people to claim God’s sanctuaries as functioning parts of their daily lives? I’m almost certain nothing like a megachurch would result. But I kind of think I’d be up for it.

Peter, Elizabeth makes a good point about megachurch culture and market economics. But still, I wonder about a place to gather as a unifying political force—and I don’t mean this in a herd mentality sense.

In any case, let’s talk about transcendence: does this movement need to transcend obvious religious frames?

PL: Right. Obvious religious frames don’t apply, and it’s lazy to try to graft conventional religious categories onto something this new and undefined. A fair number of commentators and headline writers have been using the first part of the old Stephen Stills lyric in relation to OWS: “There’s something happening here…” I wish they would add the rest of that lyric: “…what it is ain’t exactly clear.” Instead, the eager pundits rush to tell us exactly what is happening here. Tom Hayden is right to be pleading for people to “just let it breathe” in the world-historical delivery room for a little bit.

Which is to say that the Occupy movement has already achieved a transcendent character. Brother Nathan nails it: “charged with secret extremity and transcendence.”

But where does that high-voltage charge come from? Sarah, you use the term “gathering place.” Before we think about obvious religious trappings or assay organized religious support for the OWS movement, we should maybe look at the more primal religious aspect: the tented encampments of a 21st-century internal exodus, the clearing in the wilderness, the gathering at the riverside. The occupiers are creating an unusual social space where everyone is welcome on an equal footing and where everyone can become sanctified—can be made holy—during a time of great extremity and privation.

In my view the occupiers are inducing the millenarian feeling that many everyday people have been experiencing for several years—sane people, that is, who are repelled by the moronic character of Tea Party ideology.

These people long for an end to what is literally unbearable and what cannot go on indefinitely: the secession of the successful and the arrogance that goes with that, the betrayal of the poor and the contempt for workers, the violence of American empire, the ravaging of the planet, the rewarding of what amounts to criminal activity by many bankers and other one-percenters, and (my personal favorite) the subservience of the political class to the one percent.

All of this accumulated merde is deeply repugnant to the basic moral sense, not to mention core religious principles. So then into this dead land (I will forbear to quote Eliot) step some relative innocents to create their little clearings, their camp meetings, their fire circles and drum circles and whatnot. And I am not being patronizing here: the clearing dimension, the out-of-the-blue dimension, is important.

None of it will be transformational, however, unless a lot more people can be touched by the same spirit of exodus and be actively engaged in some form of active or even symbolic resistance. The vicarious identification thing will have a very short shelf life. Saying no to the death culture, to the money culture, takes practice. We would say religiously that it takes practices. How will millions of non-participants, who now feel a great deal of sympathy for the occupiers and their message, acquire those practices? How will the movement itself gather the strength needed to be able to scatter the proud on an ongoing basis? These are the big questions looming over OWS.

What worries me now is how forces that are quite clearly dead, morally speaking (the Democratic Party comes to mind), want desperately to steal the life from the nascent movement. Ditto for some other forces (e.g., the labor movement) that remain morally alive but that will face some difficulty in avoiding a degree of vampirism in relation to OWS.

So, in the midst of this roundtable, I paid another visit to Occupy DC/Occupy K Street. There were considerably more people there than just a week before, and while previously there was no encampment, per se, this week there were at least a dozen tents, and I was told upward of 400 people for a General Assembly. People were camping with their children, too.

I spent a little time under what the Rev. Brian Merritt calls the “mercy percolator,” a tree in McPherson Square where some ODC participants aim to have an interfaith service at around 12:30 each day. These were people seeking solace, communion, and yes, ritual: Merritt offered to anoint people “for wholeness,” with an equal sign on their foreheads, not a cross. He had several takers.

Merritt told me that participants at ODC asked for a religious presence, religious ritual, religious gatherings. A woman who came to the interfaith service wanted to express a joy, saying she was “happy I am living through this process, of finally standing up for something… we’re coming together of one accord for something that should naturally be the way of the world.” Peter, you talked about holiness and sanctification, but I felt that these people were seeking something more mundane: togetherness, love, simplicity.

So, Nathan, how would you interpret all this in the context of Peter’s assertion that the occupiers need to continue to elicit the sympathy of non-participants? Are there religious themes, practices, rituals, or rhetoric that can do that? Or has mainstream discourse become too imbued with rhetoric that’s been focus-grouped, massaged, and approved by what Peter calls the forces that want to “steal the life” from this nascent movement?

NS: The rituals that seem to matter most for the occupations are the ones made up, on the spot, like Merritt’s equal sign. Most religious folks who’ve shown up have rightly recognized that in order to bring their traditions to the occupation, they have to contort them a bit, and do something truly new. The obvious rubric here is the beloved kairos/chronos distinction, between the time of an eternal now, and the time that clocks tell and that history records. These occupation sites are vortexes of reinvention, where you have to run on instinct because, when there, you realize that all the features of ordinary religion—and, yes, I said “trappings” earlier in part because it includes the word “trap”—just stink of the demonic possession that infects the whole society outside. At least that’s how it can seem in the kairos phase of revolution.

What a lot of people don’t realize—it can take some time at the camps to do so—is that the point of the occupations is more to be a school than a protest. This is what the anarchist contingent of the early organizers in particular had hoped for, and I believe they are succeeding. People are learning new forms of organizing, of self-reliance, of decision-making—forms which they then take back to their own communities which they organize/occupy in turn.

For the anarchists, it’d be less important that zillions of church folks turn out for occupier marches (though that’d be briefly exhilarating), much less vote for co-opting “occupier” candidates, than for a bunch of people to start mumbling in the pews, “Hey, why don’t we start making decisions by consensus rather than letting this preacher-man tell us what to think and do?” (This is not just an anarchist conspiracy to infect the whole world, either, but a Quaker one. At Occupy K Street, for instance, there’s an interesting backstory about how they started with the Quaker business meeting model and then, by force of Occupy Wall Street’s influence, switched to the anarchist assembly.)

I would also like to interject that—and perhaps it is merely my rustiness with theories that makes me bring up a book both so (once again) obvious and so passe—I can’t help but think of Harvey Cox’s The Secular City. Big time. God dissolves into the occupation, and God’s name needs no longer be said. Whenever I come back to Liberty Plaza after some time away, there is a feeling of entering unspeakably sacred ground. Yet the moment I arrive, I’m suddenly in a whirl of frantic conversations about worldly things: finances, crises, food mishaps, small victories, marches, and so on. All those things were sacred too. The God of ordinary life is dead, resurrected in the business of self-reliance.

One thing that has been little talked-about, too, is the puritanical quality of Liberty Plaza, which reminds me of Cox’s diatribe near the end of the book (I believe) against pornography. I remember, on the night of the first Monday, when somebody slipped out a bottle of vodka and suddenly the whole tent—this was the one night they had tents up—got tense. “What are you doing with that, man?” people whispered. Some were worried that it could cause a problem with the cops.

But what I felt, and what others surely felt too, was, “Why bother with that junk when you’ve got this?” Chain-smoked, hand-rolled cigarettes were utterly ubiquitous, but that was it. As the occupation has grown enormously since, there have been more conscious, public discussions about the need to have no drugs around. There have been problems with drugs, unfortunately. But among the early occupiers, it didn’t even need to be said. God was in the house—the dead God who needed not be spoken of—and that was enough.

But at some point there’s a realpolitik question here, about that delicate balance between inspiration and action, between revelation and organizing, between consensus and the emergence of a charismatic presence—or two or three or 60—who shakes the establishment to its core. Peter or Nathan, do you think, given the way OWS has developed, that this sort of organizing is desirable—or even possible?

PL: It’s not clear that OWS folks have the intention or even the desire to build power in the classic community organizing or labor organizing sense. Which is not to say that this won’t change over time. Purification movements can move outward and can become all about taking power, or they can do their thing by way of withdrawal from the larger society. Sort of like the contrast between the 17th-century Puritans who pursued statecraft in a major way as against some of their contemporaries (e.g., the Diggers ) who just wanted to live their purified lives off to the side of the historical stage.

An intriguing sidelight here is the question of how much greater impact OWS could conceivably have without consciously going the route of a conventional Left movement and reverting to standard realpolitik considerations. As in what we used to call “leading by example,” modeling what a more equal and more just society looks like, getting rid of some of the hierarchies that corrupt not just the Wall Street/Washington culture, but large swaths of the conventional Left too.

Possibly Nathan or others on the scene can speak to the question of whether the young leaders involved are resentful about not being able to access power and wealth quickly enough, or whether they are more relieved that the burden of having to compete for winner-take-all prizes has been lifted from their shoulders. I suspect there’s a good bit of the latter going on. For some OWS participants who could advance themselves quite easily, who could even join the one percent, there may be some of the thrill of “evangelical poverty”—of choosing to be poor and to live among the poor in the manner of St. Francis and others in religious history.

So back to “shaking the establishment”: What shakes the establishment already, what gets Majority Leader Cantor and others muttering about mob rule, is the big delegitimation factor operating within OWS. This is the kind of thing Jonathan Schell wrote about in The Unconquerable World some years back; it’s the nonviolent withdrawal of popular consent, something that unjust rulers will always dread. OWS is saying to the captains of industry and titans of finance (and to their political enablers) that the house they have built is just not fit to live in.

That’s powerful stuff. Another way of saying it: very few people in American voted for, or would have voted for, the rapid financialization of the U.S. economy or the related de-industrialization of the country; no one voted for productivity gains that are purchased at the price of extreme overwork and stress; no one voted to give corporate elites a hugely oversized say in what our government is and does.

We have wearily accommodated ourselves to these new circumstances, but not happily and with grave reservations about where this is taking us. And now it seems a mainly youthful Occupy movement is giving voice to all of our previously silent reservations and shouting out a very loud non serviam! It really leaves the establishment with very little to say. What’s their response going to be: domination is good for you??

It was a little more than three decades ago when Margaret Thatcher proclaimed that “there is no such thing as society—there are only individuals.” I think it’s possible that acquisitive individualism is nearing the end of a very long run. Hooray and hallelujah if that is indeed the case.

NS: To speak of what “the young leaders” are after—they speak less of wanting “power” or “wealth” than “a voice” and the things they perceive as necessities, such as health care, education, and so forth. A transvaluation of values. Of course you could say that voice is power and that necessities require wealth, but part of what they’re doing in the “temporary autonomous zone” of the occupation is to say something different in regard to those things.

I do think that, especially as older people enter the movement, both at Wall Street and through the Freedom Plaza occupation in Washington, considerations of ordinary politics will become more prominent.

ED: It seems to me that the question is not so much about any emerging realpolitik, if we mean that in a narrowly “practical” way, with regard to material effects, consequences. The point of the OWS movement is that it is an embodiment not merely of a political ideology or social commentary, but also of an expression that gives the movement what many observe and experience as its spiritual quality. It is in this sense that, as Nathan suggests, “God dissolves into the occupation.”

“The divine is not something added to human experience from the outside,” says Leonardo Boff. “It is manifested through all experience.” An endemic immanence, if you will, that marks the protestors themselves and the protesting itself—in all of its forms—as the imago dei. This, following Peter’s suggestion, exposes the fallacy of “acquisitive individualism,” including its role within the illusion of the “one-man-one-vote” political system. Saying “I am the 99%” insists on collective identity, on collaborative being.

We’re seeing this not just in the way the Occupy movement has, in the form of street protests, moved across the country, appearing in what would seem the most unlikely of places (Occupy Orange County? Really?), but it’s also now part of an evolving network of engagement around questions of social and economic justice. The Bank Transfer Day movement, for instance, or even all the cartoons and slogans showing up all over Facebook and Twitter. The OWS movement is now the prevailing cultural conversation in America, redefining how we talk about almost everything else—money, food, politics, war, and, certainly, faith.

The body politic takes up real space. It moves. It speaks. It suffers. It celebrates. It participates in everyone’s life in one way or another. Its organization is not thus a fixed structure but an evolving being that extends itself and gathers others to it. This embodied aspect is what seems so much to confound those looking for clearly articulated demands, searching for a defined ideology, or even a realpolitik; this spiritual-political being cannot be herded into existing party-based structures. It resists co-optation, which is at least part of what we saw in the awkward OccupyATL rebuffing of Rep. Lewis.

I still think there will be efforts to make this movement part of institutions—be they unions or other secular organizations, or the faith institutions who already occupy DC (and when I say occupy here, I mean in office buildings, in the halls of Congress, the sorts that get invited to White House photo ops and will be sought after as the perceived holders of the elusive “people of faith” vote).

Things are moving as we write this. The NYPD is reportedly gearing up to evict OWS from its location. Would not having that space change things, spiritually speaking? Not in the broad sense, but in the sense of community-building, or ritual-creation?

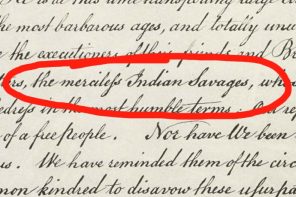

And look here: the person who blocked John Lewis from speaking at Occupy Atlanta has spoken out. He is Joseph Diaz, a 24-year-old Ph.D. candidate in philosophy at Emory University, and a self-described Christian:

Asked if he could sum up his politics with a political label, Diaz said, “First and foremost, I’m a Christian.” Then he added a lot of qualifiers like any good philosophy Ph.D. student, but in the end he told me: “I believe in the radical egalitarian community of the Holy Spirit.”

Diaz tells Salon’s Joan Walsh:

My block of Rep. Lewis had more to do with the “form” of the event rather than the content. The Occupy movement was initiated because many of those in attendance feel that rules in our current system have been unjustly bent towards (or created for the sake of the welfare of) politicians and bankers. I felt that bending the rules of the GA [general assembly] towards a politician was contradictory to the spirit of the gathering. Yes, he put his life on the line for people’s rights. Yes, he should be honored for that. But there are construction workers, firefighters, coal miners, etc., who in a very real way put their lives on the line when asked, and we would not have bent the rules for them.

Last chance: anyone feel free to chime in. We’re going to close tonight. Thanks, everyone—this has been great.

NS: Occupy Wall Street has had its share of celebrity visits and they haven’t always gone very well either. The example that comes to mind concerns a prominent black leader, Russell Simmons, who was allowed to speak during a General Assembly meeting. He interrupted the discussion at hand and gave his two cents about what, in general, the movement should do, concerning the by-then-tabled question of “demands.” He received applause and thanks. But a few minutes later, after the scheduled discussion continued about how white, male-bodied people on the plaza needed to “check their privilege,” a white, male-bodied young man got up and said something like, “Perhaps celebrities should check their privilege, too.” That got applause as well. A lot, as I recall.

It’s really unfortunate that this has become a racial issue, especially when the occupiers have problems with outreach to some racial groups already. As one black left-wing journalist suggested in a conversation I took part in recently, it may be better understood as a problem of communication styles among different communities rather than active, albeit subtle, racism.

But I do think this represents a really interesting effort on the part of occupiers to—so to speak—kill the Buddhas of power and hierarchy in our society. And celebrity really is a huge Buddha. Even well-earned celebrity. I’ve witnessed other—including white—notable people getting essentially no attention during visits to the plaza. I think it’s really telling that Lewis chose not to hold a grudge. From his remarks, I don’t get the sense that he understands the movement in a deep way, but he does clearly understand—from experience—that creating a new world can get messy sometimes.

The occupiers’ obsession with process—the General Assembly meeting, in this instance—is one really important case of the role of ritual in what they’re doing. The ritual of process comes before all else because it is the vehicle of the future, and the bulwark against compromises with the past.

The first week at Liberty Plaza, for instance, there was a decision made to march every day during the morning bell of the Stock Exchange, clogging the commute on the sidewalks. That Tuesday, the police made two incursions into the plaza during the eight o’clock hour, seemingly timed to prevent the planned nine o’clock march, making several arrests. They were hugely disruptive and rather violent. But the march went on. I looked at my cell phone when it started and saw that it was nine on the dot. I don’t recall the occupiers ever doing anything quite so on time.

AB: Last comment. I think these are all process theologians in the making. What I mean by that is, they are trying to make a space to work out, according to their own experiences of the world, how to do this “protest” thing. So far, so good. But as I said before, it’s going to take some openness on their part to realize that they need to do some bridging and framing, to use sociological terms, to build alliances with like minded folks, like African Americans, who have been doing this sort of thing in very different contexts (church/organizations).

And let me reiterate: I am for this. But what I think will make or break it is how long and how committed everyone is to the fact that things may get violent, even if they aren’t now. The thing old civil rights folks and people of color get is that the cops are not our friends. But has the average protester who’s never come up against the “man” felt that? Does that moment of realizing you can’t trust the structures become a transcendent moment that re-orients someone, or does it just send you home? Time will tell.