How did Rick Santorum roll over Mitt Romney in all those primary states? Where did the energy come from? While pundits still insist that he won’t topple the moneyed Mitt—whose campaign still generates about as much excitement as the winter sport of curling—Santorum is holding onto the spotlight long enough to put religious populism front and center.

Santorum’s red-hot religious enthusiasm is a big part of his success. Sure, there have been enough gaffes on the hustings to make Dan Quayle blush. But… one person’s gaffe is another’s bold truth. And few have been as bold as the former Pennsylvania senator. When not attacking president Obama for his “war on religion,” Santorum likes to take on so-called secularists, and climate scientists. “I’ve never supported even the hoax of global warming,” he said in February, calling it more “political science” than science.

Teaching the Impossible

And what about higher education; the liberal, secular source of so much that Santorum finds disgusting?

For those select few who do get an education, rather than working on a road crew, what should be taught in the classroom? “Darwin’s theory of evolution should not be taught as absolute fact in the science classroom,” he has mused. On law and history Santorum squares off against what he sees as a separation-of-church-and-state dogma. Earlier in his campaign he assured voters that “God gave us laws that we must abide by.” Since much of this runs counter to how courses are taught in American colleges and universities, Santorum offered a solution in an informal interview in October, 2011: “Just like we have certifying organizations that accredit a college, we’ll have certifying organizations that will accredit conservative professors. If you are to be eligible for federal funds, you’ll have to provide an equal number of conservative professors as liberal professors.”

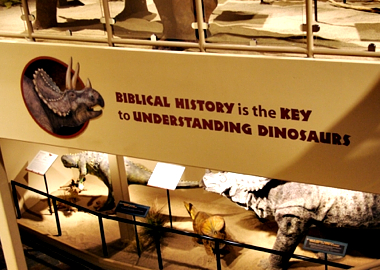

Perhaps such a university, in the name of fairness, would include paleontology courses taught by someone who believed that dinosaurs were contemporary with humans and that fossils unearthed today are of animals drowned in Noah’s flood.

Could such a university be accredited? The short answer is yes. A handful of fundamentalist colleges and universities across the country incorporate such views into their science curriculum. Knowledge denial, though, can easily find other, more subtle ways to reach willing audiences, and even creep into the classrooms of credible universities. One strategy, endorsed by Santorum and heavily promoted by anti-evolutionary groups like the Seattle-based Discovery Institute, is to falsely claim that there is a actual scientific debate going on about evolution and urge educators to “teach the controversy.”

There is, of course, no such controversy in the scientific community.

Homeschooling parents, evangelical teachers at private schools, and instructors at unaccredited religious colleges and Bible institutes share a common educational paradigm (as Julie Ingersoll has detailed here at RD –Eds). Outside the normal conversations about what counts as established knowledge, they are vulnerable to messages like that of the Discovery Institute and they are cheered that a godly candidate like Santorum is speaking for them. What are teachers to make of a claim by a scholar with scientific credentials who assures them that evolution is controversial—especially if that scholar is a religious believer who holds a PhD and shares their faith commitments?

Anti-intellectualism is deeply rooted in American evangelicalism, reaching even into the classrooms of popular schools, like Cedarville University and Liberty University (the largest evangelical university in the world), where students are taught that the earth is 10,000 years old. Millions of evangelical youth grow up hearing that there is a real debate when it comes to human origins. They also come to learn that homosexuality is a sinful lifestyle choice that can be repaired with prayer. They are taught that secular historians are suppressing the vision of the Founding Fathers and that America was supposed to be a Christian nation.

Controversies that should have died decades and even centuries ago are kept alive by organizations invested in the answers of yesteryear, often because those old answers, say stalwarts, came from the Bible and are believed to have been laid down by God. These answers informed the thinking of a long-gone society that, through the rose-tinted glasses of those nostalgic for a better time, looks moral, family-oriented, and respectful of God’s laws in ways that the present age is not.

Knowledge Denial

Ken Ham’s Answers in Genesis project is dedicated to the proposition that God wrote the Bible himself and that all knowledge needs to be based on a simple literal reading of that ancient book. As the organization’s name suggests, the book of Genesis is filled with “answers” that God provides to many important questions: How old is the earth? What is the proper relationship of males and females? What is marriage? Why were animals created? Why are there so many languages? Where did humanity originate? Why do people behave the way they do?

Some suggest that Ham’s alternative theories are benign.

“With regard to those evangelicals—and for that matter those ultra-orthodox Jews—who believe that the earth is less than 10,000 years old and either that there were no dinosaurs or that they lived alongside human beings, my reaction has always been: So what?” writes conservative radio host and columnist Dennis Prager in a response to our recent NYT op-ed on the evangelical rejection of reason. “[W]hat real-life problem is caused by people who believe otherwise?” he asks, as if knowledge is only relevant when it has a practical value for everyone alike.

Answers in Genesis argues that starting assumptions, rather than data and theories, determines whether a researcher believes the earth is six thousand or four-and-a-half billion years old. Who can be sure, anyway? Ham encourages students to ask their teachers “Were you there?” when those teachers suggest that the earth is very old, or that dinosaurs predated humans. As Ham would say, God, of course, was there and told Moses what happened “in the beginning.” That’s the “answer.” Professionally constructed dioramas in Ham’s Creation Museum show dinosaurs looking over Eve’s shoulder.

Similar knowledge denial occurs on questions of gender roles and human sexuality. Organizations like James Dobson’s Focus on the Family claim that homosexuality is an inherently perverse and sinful life choice that can be reversed. Gay adolescent evangelicals consistently experience their sexual awakening with alarm, denial, and self-loathing—with parents and other authority figures seemingly aligned in condemnation, and unavailable when needed most. But the so-called “reparative therapy” such youth are steered toward has been shown to be not only utterly ineffective but also psychologically damaging.

The American Psychological Association has stated definitively that “homosexuality is not an illness. It does not require treatment and is not changeable.” The American Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, along with numerous other professional organizations, have adopted similar stances.

But still young people, including those that frequent the clinic run by Michelle Bachmann’s husband, are encouraged to seek deliverance from their condition. The emerging acceptance of homosexuality and gay marriage, claim many evangelical leaders, reflects the moral decay of society, not an open, more accepting world. Or, as Santorum told viewers of Fox News: “There are all sorts of studies out there that suggest just the contrary, and there are people who were gay and lived the gay lifestyle and aren’t anymore.”

Amateur Hour

As conservative Christians adopt a counterview on sex and gender, they learn alternate versions of history, too. Populist historians within evangelicalism, like the prominent Texas Republican, David Barton, promote the idea that America is slouching toward Gomorrah. America is God’s chosen republic, Barton asserts: the nation has been an explicitly Christian country from its earliest days and needs to reverse its sinful migration away from its biblical roots. Professional historians, by contrast (including leading evangelicals like Mark Noll, Nathan Hatch, and George Marsden) emphasize the plurality of beliefs in early America and highlight the distance between the past and the present. Yet, how does the man or woman in the pew, faced with choosing a curriculum for church or home school, know who is presenting history more accurately?

The amateur historians, biologists, and social scientists who produce alternative curricula for evangelicals speak as beleaguered culture warriors. They offer winsome personal testimonies and refer to the Bible so often that it can sometimes seem as though their ideas actually come straight out of the Bible. They seem trustworthy—in contrast to their secular and often agnostic Ivy League counterparts. We have used the term “anointed” to reflect evangelical experts’ remarkable ability to come across as messengers from God.

These anointed leaders advance their alternative knowledge claims by casting doubt on the relevance of “secular” credentials, scientific consensus, and even higher education in general. Some of them wave away the conclusions of professionals, academics, and credentialed experts as the mutterings of eggheads with their own egghead agendas.

Glenn Beck, one of Barton’s most enthusiastic promoters, can hardly utter the word “professor” without sneering and making air quotes with his fingers. Many evangelicals, skeptical that a PhD after a name gives any reasonable authority, have come to sympathize with and even celebrate Fox News’ most well-known anti-intellectual Bill O’Reilly. O’Reilly, who pitted his understanding of science against that of Richard Dawkins in a recent show, is fond of scoffing, “sorry, professor, not buying it,” suggesting that expertise is really just opinion.

A number of thoughtful evangelicals are alarmed at the surging anti-intellectualism within their ranks. And there are many academic historians, geneticists, psychologists, and other intellectuals within the Christian tradition who do not deny the knowledge claims of their respective fields. Such believers, however, are viewed with suspicion if they do not speak the language of biblical inerrancy, anti-evolution, and conservative politics embraced by other Christians.

Take Francis Collins, for example, one of America’s most well-known scientists and an enthusiastic evangelical Christian. Despite having directed the Human Genome Project and ascended to the head of the National Institutes of Health, Collins’ credentials mean absolutely nothing to millions of evangelicals who prefer to get their science from Ken Ham, who has no stature of any sort in the scientific community.

Many conservative evangelicals reject Collins because he believes in evolution, and does not read the first chapters of Genesis literally. In his bestselling The Language of God, Collins recalls speaking at a national gathering of Christian physicians and having some of his audience walk out “shaking their heads in dismay” when he confessed to being an evolutionist. People have stormed out of Southern Baptist churches when they discovered he accepted evolution. Others have come to the microphone after a talk and implied that, in accepting evolution, he was “under the influence of the devil.”

Collins regularly gets critical commentary from non-believers like Jerry Coyne and Sam Harris, but, as he has said, the “nastiest” messages come from fellow Christians, “infuriated that someone who claims to be a believer could say these things about the truth of the evolutionary process.”

Highly publicized comments made by recent GOP candidates suggest that the stakes are incredibly high. Rick Perry made it clear during his short run that he was not on Collins’ side. At a campaign stop in New Hampshire in August he told a child that Texas teaches creationism along with evolution. (Though that, in fact, is not true.) Perry’s Texas has long drawn the spotlight in these faith-driven culture war battles. Conflicts over what kind of history should be taught in public schools, recently waged in Texas and Virginia, are no longer secular struggles. These skirmishes pit good against evil.

The Bible as Measuring Rod

Conflict between generally accepted ideas and “insider-approved” evangelical alternatives has roiled the evangelical world for decades. Thirty years ago the pop philosopher and culture warrior Francis Schaeffer (in the news most recently as an influence on Michele Bachmann) went head to head with several evangelical historians within the academy. It started when Schaeffer wrote an anti-secularist battle plan, A Christian Manifesto (1981), intended to get Christians engaged in politics. Evangelicals must “own” America’s Christian heritage said Schaeffer. The nation was founded on the principles of the Bible and the Reformation, he argued, and the founders “understood that they were founding the country upon the concept that goes back into the Judeo-Christian thinking that there is Someone there who gave inalienable rights.” Those principles had vanished in the 20th century and the government now rested in the hands of materialists and humanists.

Within a year A Christian Manifesto had sold approximately 300,000 copies, winning the enthusiastic endorsement of Jerry Falwell, who distributed it to viewers of his television program.

Evangelical historians dismissed Schaeffer as a propagandist. He was clearly not a scholar, Mark Noll told Newsweek. Writing in Christian Century, one historian called Schaeffer to task for reading contemporary politics back into the 18th century. The founders’ civil religion may have drawn on the ideals of theism, but this hardly made the country they were founding into a Christian nation.

Unfortunately Schaeffer’s views survived and are now alive and well in the messages of David Barton and the late Peter Marshall—the two most popular historians for homeschooling parents, Tea Partiers, and evangelicals in general. Barton—whose education consists of a bachelor’s degree in Christian education from Oral Roberts University—dismisses his critics, suggesting that the peer review process and the heavy interpretive component of professional history make it unreliable. He dismisses complaints about his credentials by referring to the unvarnished truth of the primary sources he employs, just as fundamentalists invoke their literal reading of the Bible. The Bible is the measuring rod.

(And as Paul Harvey discusses this week on RD, Barton has been busy stoking the fires of culture war this season, calling Obama America’s most “biblically-hostile” president.)

Biblicist watchdog Georgia Purdom recently summed up this Bible-centric approach in a review (or indictment) of our book. She explains that her organization valiantly goes “against the grain of the secular academic establishment while we stand on the authority and trustworthiness of God’s Word from the very first verse (as opposed to word of finite, fallible man).”

The intellectual trajectory of American evangelicalism is not encouraging. High-profile evangelical scholars like Duke Divinity professor Stanley Hauerwas, Francis Collins, theologian N. T. Wright, psychologist David Myers, or the historian Mark Noll often seem like guttering lamps struggling against powerful anti-intellectual winds determined to extinguish them.

The anti-evolution Discovery Institute, to take one example, spends much of its energy attacking Collins, who has neither the time nor the resources to respond. Influential conservative donors pressure evangelical college administrators to fire “liberal” faculty, creating a brain drain that leaves their respective communities even more intellectually impoverished.

Meanwhile, the turnstiles at Ken Ham’s creation museum turn briskly.