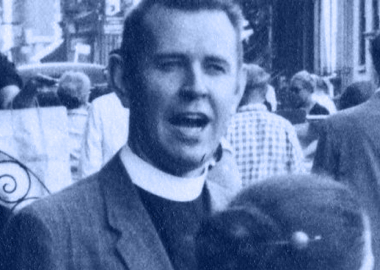

On September 13, when word came that my friend, the Rev. Howard Moody, had died at the age of 91, I remembered a self-description he loved to put out. He said that he came from a long line of “dirt farmers, renegades, and horse thieves down in Arkansas, Tennessee, and Texas.” Ordinarily, this is not a heritage that would seem to produce a man extraordinarily sensitive to the feelings and the lives of women, but that he was.

In 1957, the first year of his stay as pastor at Judson Memorial Church in Manhattan, a former Judson minister living in Florida referred a pregnant woman to him. She was seeking an abortion—a single mother of three teenaged children. A member of his church helped him locate an “abortionist” operating in New Jersey. Both Rev. Moody and the woman went to the man’s house, but were turned away when they didn’t know the correct password. It was reported that the man was “protected” by a crime mob connection and Moody described the situation as “real scary.” It was perhaps the first time he experienced something of the horrific conditions women went through when they felt they could not carry a pregnancy to term. That experience stayed with him.

When he began the Clergy Consultation Service in 1967—the group of 21 New York clergy who referred women for abortions when it was still illegal in every state—he arranged for the clergy involved to attend a demonstration that could teach them what an abortion procedure entailed and what a woman experiences in an abortion. The clergy met with a pathologist who explained the procedure using a life-size model of a woman. The doctor explained carefully when and what kind of pain the woman would feel. Again, this kind of experience drew the clergy into a far deeper understanding of the woman’s experience. Even the least empathetic among the clergy present had to imagine what it would be like to be blindfolded and helpless in the hands of strangers who might or might not know what they were doing. If a higher level of empathy is placing yourself in another person’s shoes, that demonstration put the clergy in a woman’s stirrups.

Clergy could see that the risks were enormous, but it was equally clear that women were not deterred by those risks; the law did not stop women, it merely placed them in danger.

Howard Moody said, “One can only conclude that abortion was directly calculated, whether consciously or not, to be an excessive, cruel, and unnecessary punishment.” All of us who later joined the Clergy Consultation learned the same lesson.

Howard Moody opened up the world of women to over 1,400 ministers and rabbis who later joined the Service. For those of us who sympathized with women, but had never really tried to put ourselves in their situation, he changed our lives and our ministries. More than a few of us believe that the Clergy Consultation work was the most affecting and powerful parts of our ministry. It was intense, it was moving, it was real. Howard Moody taught us a whole new dimension of empathy. Perhaps the best tribute to him came from one of our number who famously and irreverently said: “I put my trust in Howard Moody and God, in that order.” We are forever grateful for this good man.

____________

Editor’s Note:

As a generalist, an editor frequently must guide and shape work on unfamiliar topics. Having heard only that Rev. Moody was one of those “hip, old preachers in the Village,” I set out to do the obligatory research before editing the above memorial by early friend of RD, Tom Davis.

What I found is a life that defies both our coarsest stereotypes of the priggish preacherman and the conventional wisdom among today’s self-styled progressive religious leaders that finding “common ground” with uncompromising opponents is the best path to change.

In addition to Moody’s work detailed above—most notable perhaps for the way in which he showed great leadership by following and learning from women, and not by lecturing and telling them what to do—the Reverend ran support groups (and memorials) for gay men during the early days of the AIDS crisis (when few would acknowledge its existence, much less provide support), spoke out against draconian drug laws that disproportionately effected the poor, and was a supporter of free speech, particularly when it came to artists, with whom he clearly felt an affinity.

RD contributing editor Peter Laarman, who effectively succeeded Moody and served as senior minister of Judson from 1994 to 2004, writes:

Howard had an electric and electrifying personal presence; I think of it as the aura of a truly fearless human being. There aren’t that many. You got the sense that he had done the intellectual and spiritual work at such a deep level that it was in his bones. A telltale sign: when Howard began his Judson work, 99% of working clergy had no real feeling for artists, and most were even slightly afraid of them as some kind of alien species. Howard not only loved all artists but he gravitated toward the edgiest and most experimental among them: the outlaws. I think he reveled in the avant garde because he himself was actually part of it: completely breaking apart what it had meant to be a mainline congregation and creating something new and amazingly vibrant on Washington Square South.

But what may ultimately be most endearing was his gift for exploding the cheap piety we’re still imprisoned by as we head toward the 2012 elections. Nowhere was this on display more prominently than in his distinction as the first author to have the word “fuck” printed in the Village Voice. In “Toward a New Definition of Obscenity,” Moody, who had by 1965 screened banned films in church and registered voters in the South, wrote that:

For Christians the truly obscene ought not to be slick-paper nudity, nor the vulgarities of dirty old or young literati, nor even ‘weirdo’ films showing transvestite orgies or male genitalia. What is obscene is that material, whether sexual or not, that has as its basic motivation and purpose the degradation, debasement and dehumanizing of persons. The dirtiest word in the English language is not ‘fuck’ or ‘shit’ in the mouth of a tragic shaman, but the word ‘NIGGER’ from the sneering lips of a Bull Connor. Obscenity ought to be much closer to the biblical definition of blasphemy against God and man.

I have no doubt that there are young Moodys out there (or that he was a far more complex figure than hagiographies allow). Of course should a new Moody be heard beyond the walls of Democracy Now or Pacifica radio, a flurry of op-eds would contend that she’s just the Left’s version of Tony Perkins, and we’d nod piously as she struggled for funding.

*Thanks to obituaries by the Judson Memorial Church (which will host a celebration of his life on Nov. 10), the New York Times, and RH Reality Check.