“Civil religion” is one of those twentieth-century terms that seems rather quaint today. And yet, as the Supreme Court marriage cases are heard this week, it seems alive and well, and living in unusual spaces.

On the surface, the Windsor and Perry cases are about constitutional rights, and the limits of federal government (not to mention the procedural questions of standing, mind-numbing to non-lawyers but conceivably dispositive here). Does the combination of federalism and an equal protection violation justify overturning the Defense of Marriage Act? What is the relationship between the US Constitution, the California constitution, and a voter initiative that defines certain rights?

And yet, these questions are surely not the real issue.

Nor is the bundle of rights that is conferred by legal marriage. Yes, in Edie Windsor’s case, the denial of those rights cost her hundreds of thousands of dollars. And, as I was interviewed by two local television stations this week, I was asked both times about how much my partner and I are affected in material terms: income tax, social security, hospital visitation rights, that sort of thing. Media trained as I was, I tried to steer the conversation toward deeper issues, but both reporters ended up using the details. Tell me how much it costs.

Yet obviously, these financial and other burdens, while significant for some and extremely significant for others (e.g. American citizens married to non-citizens), are not really what these cases are about. The Supreme Court is ostensibly an organ of the federal judiciary, but they are sitting, by proxy, as a civil religious court deciding whether it’s okay to be gay—or even if it isn’t, whether the government may enforce that view. The latter may be a secular constitutional question, but the former certainly is not. And yet surely it’s what the protesters, pundits, and politicians on all sides are really talking about.

This has led to numerous absurdities. Just the other day, Ralph Reed, formerly of the Christian Coalition, was suddenly speaking the language of secular constitutionalism. “Do we have a compelling interest,” he asked rhetorically on Meet the Press, “in strengthening and supporting the durable, enduring, and uniquely complementary and procreative union of a man and a woman?”

Reed knows his constitutional law as well as I do; “compelling interest” is a legal term of art, and refers to the exceptionally high burden the government must show to justify discrimination. And of course, “durable, enduring, and uniquely complementary and procreative” are, in theory, secular philosophical values. But does anyone think, for one second, that they’re really what Reed has in mind?

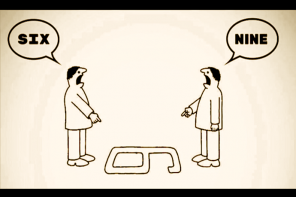

Obviously, Reed—who now works for the “Faith and Freedom Coalition”—is talking about Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve. He’s doing a kind of constitutional drag performance for the press, dressing his religious values in secular sequins and pearls, but we all know what’s beneath the costume, right?

Likewise with those on the pro-LGBT side. We, too, change costumes depending on which ball we’re attending. At the Supreme Court, Boies and Olsen et al. are, of course, making arguments about rights and laws. But in the LGBT movement’s mainstream messaging, we’ve long since abandoned “rights,” which tests poorly with moderates, in favor of values like fairness, equality, and freedom. There is some overlap—after all, the Constitutional clause in question is about Equal Protection—but the deeper questions, we know, are not constitutional but religious: the fundamental dignity of each person; the relationship of tradition to science, conscience, and change; the meaning of religion itself.

So is all of this public rhetoric hypocrisy?

Some, but not all. Sure, it’s obvious that Ralph Reed wants more conservative Christian values, and I want less of them. It’s also laughably obvious that the conservative Catholic justices vote like conservative Catholics, Justice Scalia’s loud protests notwithstanding. Back in law school, this notion was called “legal positivism.” Forget rules and principles, this cynical theory holds; Scalia decides what Scalia decides, and it counts because he wears the robe. And indeed, when Scalia himself jettisoned his much-beloved federalist principles in order to anoint George W. Bush as president in 2000, the positivists had a field day.

But that’s not quite it. As inappropriate as the Supreme Court may be as an adjudicator of theological rights and wrongs, it is the high court of American “civil religion”—by which I mean not the original Rousseauian conception of core religious beliefs, but the “civil religion” elaborated upon by twentieth century political theorists, anthropologists, and sociologists. Drawing parallels with Greek and Roman civil religion, which served to unite the polis and justify the state, scholars such as Martin Marty and Robert Bellah have described a generally Christian, theologically non-specific civil religion in which supposedly secular institutions fulfill essentially religious roles.

Not coincidentally, civil religion played a central role in the 1960s civil rights movement; then, too, secular rights were at issue, but the values in play were obviously trans-secular. Civil religion venerates its sacred texts (the Constitution chief among them), while disagreeing as to how they are to be interpreted. And it has its sacred tenets about the American nation, even if their meanings, too, are hotly contested—no one argues that we should be against liberty and equality, for example; we just argue as to what those terms are supposed to mean.

Moral moments—the Civil War, the Great Depression, and to a lesser extent our current moral moment on LGBT equality—are times in which this civil religion becomes more apparent, for better or for worse. Certainly, more radical activists find the very notion deplorable, and argue that the state should get out of the marriage business (for example) entirely. But they are on the fringe, and I think they’ll stay there. For the vast majority of Americans, our country is a place in which ethical values are adjudicated, even if our official institutions officially deny it. Fortunately, one of those values has to do with the separation of church and state, so the zone of adjudication is somewhat limited. But there’s no sense in denying that civil religion is at play in these contemporary debates, and has been in similar debates for two hundred and thirty years.

My intention is neither to be fatalistic about the ineluctably religious nature of these questions, nor to be optimistic that the Supreme Court will necessarily get this one right. Indeed, many anti-equality writers are cautioning the Court not to repeat the mistake of Roe vs. Wade, when (so they say) judicial fiat ended a public conversation and created a bitter backlash. Yet however much it may disturb those of us on the more separationist end of the spectrum, this moment is a moral one, and this institution is the venue for it. And even the drag is part of the ritual.