Most of the homeless people in Berlin are Jewish. Some of them wear tattered black yarmulkes, their matted beards clinging to emaciated cheeks. Their eyes are sunken and glazed as they plead with German passersby for help. It’s like this all over Germany. The street corners and slums of every major German city, from Munich to Nuremberg, are filled with Jews struggling to cope with extreme poverty, many of them addicted to drugs and alcohol.

The same is true of German prisons: almost half of all incarcerated Germans are Jewish, despite Jews making up only 12% of the German populace. Recently, controversy erupted when a German police officer shot and killed an unarmed Jewish teenager from a poor neighborhood. In an online campaign to raise money for the policeman, some of the 78,000 supporters wrote messages telling angry members of the German Jewish community not to “act like animals” and pledged over 250,000 Euros to the policeman and his family.

Of course, most of Berlin’s homeless population is not Jewish. Most German prisoners are not Jewish. The idea of a German policeman killing an unarmed Jewish teenager sounds so anachronistic as to border on 21st-century-impossible. But what if all of the above were true? Wouldn’t it be phantasmagorically obscene and unbearable? And wouldn’t its unbearableness be precisely due to context and history? Because of centuries of horror that Europe inflicted upon the Jews, culminating in a genocide that wiped out a third of the world’s Jewish population? If all of the above were true, would we hold the German government and German citizenry writ large responsible? If so, how?

The aforementioned numbers and anecdotes are fictional in the German context, and are extracted from the reality of the black community in America. There are, of course, vast differences between the two cases, which I will address later on. My intention is not to bluntly posit an equivalency between Jewish history in Germany and black history in America, or to minimize the uniqueness of either. My aim is to enter into conversation with two black American writers—James Baldwin, who wrote and lived through the time of the Holocaust and American segregation, and contemporary writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, a senior editor for The Atlantic—about the profound and extant points of synthesis between our peoples’ respective stories, and what can be learned therein.

If we cannot pursue justice, who are we?

When they came to America, most of my ancestors were marginalized and denied entry to American whiteness. Today, however, I benefit as much as any other white-skinned person from the privileges and prosperities that white America reaped from the crime of slavery. I benefit from the injustices that continue to this day, including astronomical rates of incarceration in profit-driven prison systems, and bank-enforced poverty (the rate of poverty among black vs. white Americans hasn’t changed since the 1960s).

In The Fire Next Time, whose essays were first published in 1962 but damningly relevant 52 years later, James Baldwin writes that for blacks, “[American society] is entirely hostile, and, by its nature, seems determined to cut you down …[as it] has cut down so many in the past and cuts down so many every day…The brutality with which Negroes are treated in this country cannot be overstated, however unwilling white men may be to hear it.” This brutality is not incidental but intrinsic to America and its material prosperity.

Spiritually speaking, I am—as are we all—devastated and degraded by the societal decay that cannot but result from this vicious injustice. It is untenable for us as Americans, as human beings, and as Jews.

Combining two ancient Jewish teachings, the question about our collective future becomes this: if we cannot pursue justice with the stranger and the oppressed, who are we? Put differently, the imperative to do justice—not in some hypothetical, metaphysical realm, but here and now, where we stand—must be seen not as a suggestion for altruism or charity, but rather as an opportunity to reclaim and reinvigorate what is left of our rapidly fading legacy, culture and collective spirit, and to join in an effort to unburden America of the weighty, shameful yoke of its legacy of racial brutality.

In May of this past year, Ta-Nehisi Coates penned a searing article in The Atlantic entitled “The Case for Reparations.” In it, he detailed the history of American oppression of black people, from slavery to Jim Crow to racist housing police, and called, inter alia, for Congress to establish a “Commission to Study the Reparation Proposals for African-Americans,” as urged by Congressman John Conyers’ (D-MI) H.R. 40, a bill that’s been introduced (and ignored) multiple times.

Following the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Coates reiterated the urgency of his case, clarifying that a call for reparations is not an exercise in political theory but rather a suggested praxis connecting directly to dignity, hope and, in some cases, survival. In the original essay, Coates concludes by offering a potential historical parallel: reparations paid by the German state following the Holocaust. “Only 5 percent of West Germans surveyed reported feeling guilty about the Holocaust, and only 29 percent believed that Jews were owed restitution from the German people,” writes Coates.

Nonetheless, as part of the framework of broader reparations that the Allied Powers obliged the German government to pay, it was eventually agreed that reparations would be paid to the State of Israel and the World Jewish Congress. While the economic boost to the new Israeli economy was significant, Coates argues that the greater impact wasn’t economic: “Reparations could not make up for the murder perpetrated by the Nazis. But they did launch Germany’s reckoning with itself, and perhaps provided a road map for how a great civilization might make itself worthy of the name.”

More than money

The two cases, post-Holocaust Germany and post-slavery-and-segregation America, are, of course, not identical. The German state’s most severe crimes against the Jewish people were concentrated into a relatively short and exceedingly brutal sliver of history, after which most of the surviving Jews left Germany (and Europe). Germany, in turn, was forced by international powers to reform and repent. And pay.

America’s crimes were drawn out over centuries. And while the Civil Rights Movement forced certain improvements to be made, America has never really had to reckon with its past and dramatically change course as a result. (One need simply walk around the hallways of public schools in any major American city to interrogate the extent to which segregation has truly been abolished in that venue.)

But there are meaningful similarities. As Baldwin observed, also in The Fire Next Time, black Americans were far less surprised by the Holocaust than their white Christian counterparts:

For my part, the fate of the Jews, and the world’s indifference to it, frightened me very much. I could not but feel, in those sorrowful years, that this human indifference, concerning which I knew so much already, would be my portion on the day that the United States decided to murder its Negroes systematically instead of little by little and catch-as-catch-can.

If Coates is right that reparations at least partially correlated with German societal and cultural reckoning, then one can see their fruits in Germany today. Last month, following a number of horrid, hateful slogans chanted at Jews (in the context of otherwise legitimate protests against Israel’s attack on Gaza), and a number of violent incidents, there was a large public vigil in Berlin to protest anti-Semitism. Among the attendees were German President Joachim Guack, members of Germany’s parliament, leaders of both of the country’s major churches, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who declared: “Jewish life is part of our identity and culture… Whoever discriminates and ostracizes has me, all of us, and the majority of the people in Germany against them.”

Then there’s America. Following what many have framed as the execution-style killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri—an incident whose contours were tragically familiar—there were a multitude of demonstrations against racism and state-sponsored brutality, some of which were met with tactics widely acknowledged to be disproportionate and aggressive. These rallies and vigils continued for weeks, and were renewed again this month, in Ferguson and elsewhere. Through all of it, it appears that only a single U.S. congressperson attended a demonstration in Ferguson, Rep. William Lacy Clay (D-MO), who walked the length of the demonstrations along with Rev. Jesse Jackson.

After a lengthy discussion of ISIS and Iraq, President Obama spoke directly to the people of Ferguson in a televised statement: “So, to a community in Ferguson that is rightly hurting and looking for answers, let me call once again for us to seek some understanding rather than simply holler at each other.” Compared to Merkel’s in-person, adversarial declaration of solidarity with Jewish Germans, President Obama’s televised call for understanding is milquetoast.

This, of course, is not a question of personal politics or individual temperaments. Angela Merkel is, to my understanding, no great radical, while Barack Obama, according to Ta-Nehisi Coates in Fear of a Black President, “is not simply America’s first black president—he is the first president who could credibly teach a black-studies class.” This is about national political cultures, which brings us back to the idea that reparations are not only about money: They’re about symbolic and spiritual recognition of historical and present wrongs, about transforming national culture, and about governments and citizens taking collective responsibility for collective crimes.

I hold that American Jews have a unique obligation to support reparations for African Americans. Not because we are uniquely guilty for America’s crimes against black people; and certainly not because, as some anti-semitic conspiracies would assert, we have unique control over this country’s finances and resources.

American Jews have a unique obligation to support reparations for African Americans because we, as a collective, know the meaning of vicious identity-based oppression. And because, as a collective, we have been freed from the yoke of much of our historical suffering. This is not to imply that anti-semitism has disappeared—it hasn’t—but we must appreciate the implications of elected leaders from all over Europe, the epicenter of our historical affliction, standing by our side in response to threats of anti-semitism. This may be only a sliver of the historical debt we are owed. But it is a sliver.

In America, meanwhile, when a young black man is killed at the hands of those claiming to enforce the law—whether official as in Darren Wilson’s case or self-appointed as in George Zimmerman’s—the country as a whole seems to forget that African Americans are even owed a historical debt, fatuously shuffling our collective feet, fundraising for the killers, or laughing to drown out the ghosts of American cruelty. As Jews, our historical familiarity with oppression and our current collective access to privilege ought to manifest as a responsibility to align with those most oppressed today, wherever we stand. As American Jews, we have a unique obligation to support reparations for African Americans because so much of white America, addicted as it is to the fantasy of a post-racial era, does not appear ready to do so.

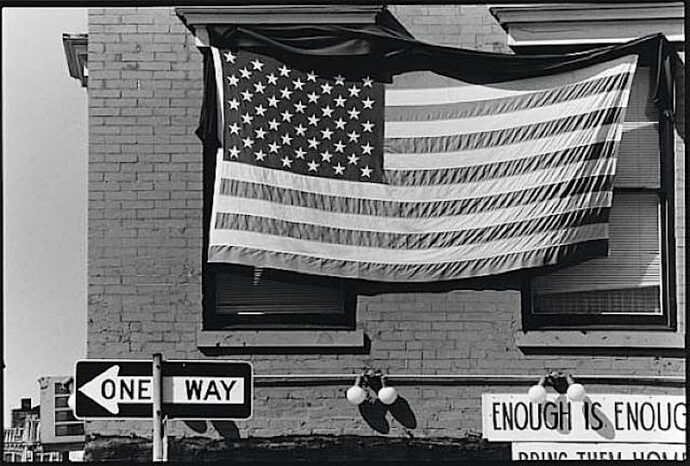

And then the chasm between obligation and action. In our communal meeting centers and houses of worship, we wave the legacy of Jewish Freedom Riders like a flag, happily glossing over all of our so-called leaders who joined in to chide Dr. King for “getting ahead of his time.” We chant “Justice, Justice We Shall Pursue.” Will we, or will we continue to plod along contentedly with our newfound comforts? Can the horrors of the history of the Nazi Holocaust and the relative depth of German reckoning in its wake teach us something about how to be and what to do in this country? Could reparations be a major part of this? At the very least, increased efforts, awareness and activism could lead to what Baldwin called for in another breathtaking, complicated essay from 1967, Negroes are Anti-Semitic Because They’re Anti-White: “A genuinely candid confrontation between American Negroes and American Jews.”

Isn’t now the time for communal awakening? Shouldn’t we look for leadership from the recent initiative of Jews pledging support for cooperatives in the South as part of a campaign to commemorate 50 years since the Mississippi Freedom Summer? And from the 30 American Rabbis who went to march in Ferguson right after the high holidays this year? And from the activists working tirelessly in groups like Jews for Racial and Economic Justice? And particularly from those in the black community who are leading this struggle, in Ferguson, in Ohio, in New York, in Jackson?

The first step: For those who have not yet read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay on reparations, do so now. And then my call, to my community and outwards is this: let’s make our grandparents and grandchildren proud, and commit now to doing what we can do—and much more than we have been doing—to support the black-led struggle for freedom, democracy and justice for all people living in this broken country.