As a scholar of American evangelicalism, I often spend my time writing and teaching about the overt beliefs and practices that White conservative Protestants employ to further entrench Christian nationalism and White supremacy as American values. White evangelicals are, for better or worse, constantly saying the quiet part out loud. From their “segregationist theology” that turned upholding Jim Crow laws into a biblical mandate in the 1950s to their wholesale rejection of critical race theory today, White evangelicals across the decades have actively upheld White patriarchy at every turn.

Christian Imperial Feminism: White Protestant Women and the Consecration of Empire

Gale L. Kenny

NYU Press

Feb, 2024

Christian Imperial Feminism tracks the evolution of mainline White Protestant women’s ecumenical organizations, beliefs, and practices through the early decades of the 1900s. At the turn of the century, White women exercised their limited authority in the church through gender-segregated mission societies, which simultaneously provided them the opportunity to demonstrate familiarity with (and mastery over) other nations and cultures. Kenny argues that White Protestant women’s missionary guidebooks and pageants “established cosmopolitan aesthetics and structures of feeling” that shaped their budding Christian feminist values.

By the 1920s and 1930s, many mainline Protestant churches had subsumed their women-run mission societies into all-gender (and usually male-dominated) organizations. White Protestant women were forced to reevaluate their aims, and many of them chose to turn their attention to domestic Christianization as their new mission front. During a time of heated schisms among fundamentalist and evangelical groups and amidst the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan rallying against immigrants, people of color, Catholics, and Jews, mainline Protestant women’s church councils increasingly emphasized interdenominational, interreligious, and interracial cooperation.

Mainline Protestant women’s organizations may have been increasingly interracial and anti-nativist, but Kenny argues that the missionary impulse behind their “Christian Americanization” efforts betrayed its own kind of imperialism. Such groups extended the hand of friendship to racialized European immigrants and new Black neighbors from the Great Migration, but nevertheless characterized such groups as practicing “ethnic” religions that could benefit from the civilizing example of White Protestant culture.

It was within this patronizing multiculturalism that White Christian feminism took shape. White Protestant women characterized other religions’ (and “ethnic” Christians’) oppression of women as endemic to their faith, while at the very same time arguing that oppression of women by White Protestants was simply a misinterpretation of an otherwise liberating faith. While White Protestants and religio-racial “others” could all benefit from cultural exchange, White Protestant women positioned themselves as the arbiters of such exchanges, reinforcing their own beliefs, practices, and identities as normative and authoritative.

Perhaps the most valuable insight of Kenny’s work is her identification of the politics of sentiment at play in White Protestant women’s religious imagination of the racial other. Early 20th century missionary pageants depicting Hindu or Muslim women finding liberation in Christianity, for example, used racist tropes to further the feminist aims of White Protestants by associating the “backwards” oppression of women with the racial and religious other. Christianizing and “liberating” those of other nations, then, performed the emotional work of legitimizing White Protestantism as the ideal religion and tied women’s liberation to White Protestantism.

In the 1930s and 1940s, as White Protestant women sought to racially diversify their organizations, they often focused on the spiritual benefits of racial and cultural exchange, centering their own religious and emotional development. As Kenny writes:

Like playing a part in a missionary pageant, attending an interracial meeting generated a similar thrill of inhabiting God’s diverse kingdom while also leaving the White participant confident in her superior Christian virtue and liberal cosmopolitan attitude.

While these interracial efforts often centered the benefits to (and experiences of) White women, they also underscored White Protestantism as the only appropriately dispassionate arena for cross-cultural exchange. Kenny contends that historians must reckon with the lasting impact of White Protestant women’s attempts to “manage” race through the auspices of organized religion and the language of proto-second wave feminism. Such efforts helped shape American conceptions of the secular—which Kenny specifies as “not the absence of religion, but what scholars define as the means for governing religion.” In other words, she argues, “White Protestant women’s work to define permissible religious beliefs, emotions, and practices contributed to a largely Protestant-informed normative secularism in the United States.”

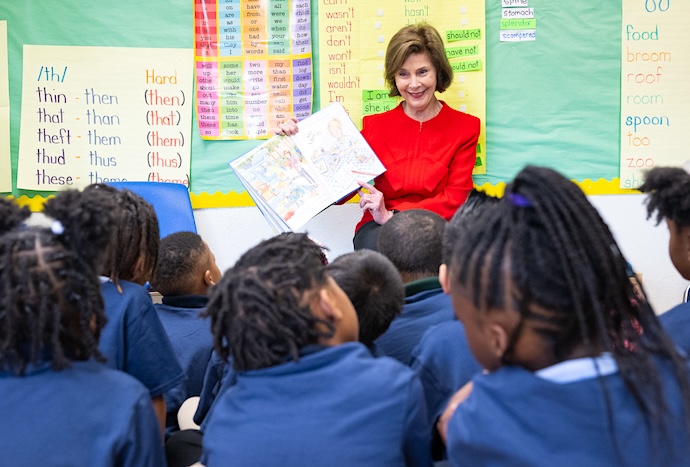

The continuing influence of Protestant-inflected secularism that advances American imperialist goals through the language and emotional politics of White feminism will, perhaps, come as no surprise to anyone who’s ever read a newspaper. Kenny briefly gestures at this reality in her conclusion, drawing a through-line from early 20th century White Protestant church women to Laura Bush’s 2001 radio address on the Taliban’s oppression of women in Afghanistan.

In this famous speech, the First Lady contrasts the “brutal” Taliban with the distress and concern of “civilized people around the world,” ending with a call to Americans to be “especially thankful for all of the blessings of American life.” And yet, in one important way, Bush diverges from her Protestant forebears. Describing the Taliban as inimical not just to Christian values, but to Muslim values, Bush says:

The poverty, poor health and illiteracy that the terrorists and the Taliban have imposed on women in Afghanistan do not conform with the treatment of women in most of the Islamic world, where women make important contributions in their societies. Only the terrorists and the Taliban forbid education to women. Only the terrorists and the Taliban threaten to pull out women’s fingernails for wearing nail polish.

With this rhetoric, Bush invites Islam under the umbrella of what once was characterized as a tri-faith America. And yet, Islam is only welcome at the table inasmuch as Americans understand it to comport with their own vision of freedom and progress—a vision largely defined by White Protestants.

Christian Imperial Feminism is, at its heart, a solid historical account of mainline White Protestant women and their shifting vision over the course of the first half of the 20th century. The Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, and other domestic and geopolitical events would eventually push some White Protestants to more fully embrace anti-racist and anti-imperialist theologies and political stances, but Kenny rightly identifies the lasting influence White Protestant churchwomen’s Christian imperial feminism has had on normative understandings of American values as a universal balm to women’s oppression and religio-racial “backwardness.”

This type of Christian imperialism is obvious among the vociferously rightwing: one need look no further than Republican Senator Katie Britt’s recent rebuttal to President Biden’s State of the Union address, during which she positioned Chinese communists and murderous illegal immigrants as existential threats to “innocent Americans” relying on God’s guidance to achieve their American dream. But the subtler, and perhaps more useful, aspect of Kenny’s work might lie in its ability to inspire readers to consider how Protestant imperialist logic can also underlie more progressive movements and organizations.