Behold, I am doing a new thing.

Isaiah 43.19

1.

Of theological projects perhaps none is so vexed as that of trying to develop a biblically-based politics in the context of a secular democratic state. The available models, which roughly correspond to Hebrew and Christian portions of Scripture, are tribal and theocratic in the first case; apocalyptic and apolitical in the second. Neither provides an easy or applicable blueprint for active citizenship under the Constitution of the United States.

No doubt the core demands of justice, mercy, and the respect due to the human person are clear and generally consistent throughout the biblical text. How to achieve those principles within our present political context remains problematic. The Bible is richer in precept than in precedent.

The difficulties are by no means restricted to biblical literalists, which is to say that biblical literalists are not the only ones trapped in the past. The pop historicism of the typical “Jesus book,” eagerly casting him as a liberal at home in modernity, is often no more helpful, politically speaking, than the literalism that wonders aloud if any dinosaurs made it onto the Ark.

I’m not pointing fingers here so much as preparing to lay down some of my cards. Few theological positions are dearer to me than those of the Liberation Church—I have a print on my office door of Orozco’s revolutionary Christ, chopping down his own cross— but the idea of Jesus as a revolutionary, even a nonviolent revolutionary, is admittedly as big a stretch as the idea of Jesus as a circus clown or a mega-church minister. As for those revolutionaries who do appear in the Bible, the Maccabees and the Zealots, they look more like Taliban than Zapatistas.

Nevertheless, people with a patently literalistic approach to the Bible have more at stake than I do. Inevitably they must choose between attacking the ideals of a pluralistic democracy or relinquishing their own hermeneutics. Opt for the first, and you’re soon trying to curtail the civil rights of gay and lesbian people on the basis of a verse in Leviticus. Opt for the second, and you almost don’t need Leviticus. You’ve solved the problem by eliminating the suppositions that gave rise to it, sort of like healing angina by cutting out your heart.

2.

I came to this subject in a somewhat roundabout way. Not long ago, depressed as many others are by the dismal state of our national affairs, and writing a number of pieces to address it, I challenged myself to frame my political “take” in a single sentence. Put in the simplest terms possible, what did I see?

The best I could manage was two sentences. They went like this:

Nothing short of a revolution can reverse the course our country has taken.

The people most capable of making a revolution are on the counter-revolutionary side.

The conclusions were disturbing but hardly new. George Orwell seems to have had roughly the same thing in mind when he wrote: “It is exactly the people whose hearts have never leapt at the sight of a Union Jack who will flinch from revolution when the moment comes.”

It wasn’t difficult to find a religious corollary to Orwell’s remark. If the biblical tradition has anything substantive to offer to our political dialogues, it will come from people who do not flinch at the suggestion that it might. It will come from people who are not squeamish about saying so. In short, it is likely to come from the very same people whose politics are presently at odds with my own.

But that observation brings us round to the problem with which we started: How does one derive a political outlook from a text with few parallels to the political context in which we live? In other words, how do you ask “What would Jesus do?” when the one thing Jesus couldn’t do was vote?

3.

To make a start, we might turn to the one thing Jesus could do, and did do, which was read and respond to those texts regarded as scripture in his day. His approach was simultaneously reverential to those texts and radical in its application. He was neither a knee-jerk literalist nor a politicized archaeologist. To read his utterances on the Sabbath, on divorce, on the resurrection of the dead, is to see someone who treats the scripture as a text binding upon him but always liberating in the way that it binds. The Word speaks to the moment. “It is written,” Jesus says, never “It was written.”

In this he is very much in the tradition of the Hebrew prophets. When he reads from the scroll of Isaiah about being called to “preach deliverance to the captives,” then adding, “Today this saying is fulfilled in your ears,” he echoes another passage from the same prophet:

Remember not the former things,

nor consider the things of old.

Behold, I am doing a new thing.

And there’s nothing new about his saying so. The Exodus was also a new thing, so new that the Pharaoh is quite right to say he does not know the god of Moses, this god who speaks for slaves. The religion Pharaoh did know, the religion of empires, was based on the repetitive patterns of nature and was thus fundamentally conservative. In contrast, the prophetic religion of Isaiah and his contemporaries posits historical change, guided by a living God who refuses to be locked inside the shell of any graven image, tradition, or dynasty. Perhaps it was said of old that when parents ate sour grapes the children’s teeth would be set on edge, but according to Ezekiel and Jeremiah, that is over now. Perhaps it was said in the opening chapter of Jonah that God will destroy Nineveh, but when the people of Nineveh repent, then so does God, much to Jonah’s chagrin. Perhaps it is said in the Torah that no male with crushed or missing genitals can enter the Lord’s tabernacle, but if Philip finds an Ethiopian eunuch desiring to be baptized, he will not refuse.

“Search the scriptures,” Jesus says in the Gospel of John, “for in them you think you have eternal life.” The texts are essential, he seems to be saying, but they are not definitive. They point to the God who can always do a new thing—who is doing one now.

4.

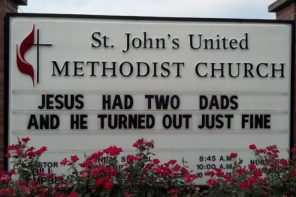

Perhaps no contemporary example better illustrates our estrangement from this tradition than the current debate over gay rights, gay anthropology, and gay vocations that has divided most mainline Protestant churches.

Predictably the “traditionalists” seize upon any stray verse in Leviticus or Romans that would seem to condemn homosexual love. Or else they beg the question through a dubious reading of the Sodom story. (I’m of the same mind as the writer Richard Rodriguez in betting that the “redneck rowdies of Sodom” were “heterosexuals all.”) Just as predictably, if somewhat more imaginatively, the “progressives” put forth the suggestion that David and Jonathan were lovers (as if it would prove anything if they were), or write an addendum to that Pauline verse so widely (and weirdly) adored, that in Christ there is neither male nor female, slave nor free. Good news for the slave, to be sure, but bad news for anyone inclined to take comfort from Mary Magdalene’s gender.

Neither “conservatives” nor “progressives,” it seems to me, read the signs of the times along with the deepest implications of the text. Neither speak with the full-throated “Behold!” of the Prophets and their Nazarene son.

If Jesus were to speak on “the gay issue,” I imagine him making an utterance that would unsettle and challenge all factions. I imagine him speaking to “the marriage question” with something like his parable of the marriage feast. Historically only heterosexuals were invited to marriage, but they have abandoned it in ever-increasing numbers. Like the invited guests in the parable, they’ve been busy with other affairs. Therefore, God is doing a new thing in calling gay and lesbian people to sacramental monogamy and partnered parenthood. And that is also a very scary thing because it means not only that traditional understandings of marriage are passing away; it means that traditional understandings of what it means to be gay and lesbian—Sappho’s understanding no less than Queen Victoria’s—are also passing away. “Behold, I am doing a new thing.”

It all sounds rather disturbing, humbling, and yes—horror of horrors—“judgmental.” Prophecy is by its very nature judgmental. But it is seldom predictably judgmental. “The stone that the builders rejected has become the chief cornerstone.” That sexual minorities might count as a new cornerstone in what we think of as “family” is not likely to be acceptable to most fundamentalists. But on the day when such an interpretation of the text became acceptable to them, it might also become descriptive of them.

5.

But the fundamentalist—and not only the fundamentalist—will object that I am missing the most important meaning of the words “prophecy” and “prophetic”: namely, that the prophet does not speak for himself. The prophet, according to traditional understanding, is not simply a person who “reads the times” in the light of revealed religion, an op-ed writer in long robes. A prophet brings revelation. A prophet is literally the mouthpiece of God.

One cannot answer such an objection without accepting its main premise. The only feasible answer is to raise this question: How many of us are longing for the mouth to speak? How many of us, even and especially the most traditional, believe in a God who can do a new thing? We have plenty who believe in God, and plenty who believe in new (“progressive”) things, but neither is the answer to my question.

“Behold, I have come to set fire to the earth,” Jesus says. We risk kindling fire whenever we strike together the two stones of the world God intended and the corruption we have made in its stead. Strike the prophets on the profits, and you may get fire. No sect within the biblical tradition has a monopoly on striking insights; it remains to be seen who will produce the fire.

The lack of an easy analogy between the political systems of the Bible and the systems that now govern us is frustrating only so long as our hermeneutics remain petrified in archaeology or nostalgia. Might it be that the lack of an easy political application is itself prophetic? Eye hath not seen and ear hath not heard what we are called to create. To put the matter in terms of Christian symbolism, the blueprint for the Kingdom of God is no more in the texts of the Bible, or in the US Constitution, than the Body of Christ is in the tomb. There is need of a new thing. There is need of a new heart to desire that new thing. The old words tell us so, again and again.