Chances are you have heard something about the Rev. William Barber II.

He is the giant of a man (in more senses than one) who launched the Moral Mondays movement in North Carolina in 2013—a movement that has since spread to other states and is now formally known as the Forward Together Moral Movement.

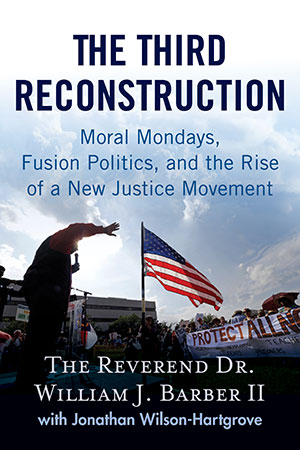

Rev. Barber has now put his thoughts together in a book newly published by Beacon Press, The Third Reconstruction: Moral Mondays, Fusion Politics and the Rise of a New Justice Movement. Barber was assisted in the book’s preparation by his fellow NC-based spiritual revolutionary, Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove. The book should be read by anyone who cares about the unfinished human rights revolution in the United States.

The first thing that Rev. Barber makes clear is that Moral Mondays didn’t come out of nowhere, just as the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 didn’t come out of nowhere. There were seven years of preparation and careful coalition-building that, by April 2013 when it burst into full public view, could claim 140 participating organizations.

One might say that Rev. Barber himself is the product of careful preparation: his late father, also a Disciples of Christ/Christian Church minister, was a noted thought leader and freedom fighter who moved his family from Indianapolis to North Carolina to challenge the remnants of school segregation following the Brown decision. As early as 2005, when he assumed its presidency, the second William Barber was already refashioning the North Carolina NAACP from a fairly quiescent group into a real thorn in the side of the status quo. And all the while, from 1993 to the present day, Mr. Barber has faithfully served as pastor of Greenleaf Christian Church in Goldsboro, NC. Appropriately named, Greenleaf under Barber’s leadership has itself been a transformational powerhouse in a small community. No surprise there.

One might say that Rev. Barber himself is the product of careful preparation: his late father, also a Disciples of Christ/Christian Church minister, was a noted thought leader and freedom fighter who moved his family from Indianapolis to North Carolina to challenge the remnants of school segregation following the Brown decision. As early as 2005, when he assumed its presidency, the second William Barber was already refashioning the North Carolina NAACP from a fairly quiescent group into a real thorn in the side of the status quo. And all the while, from 1993 to the present day, Mr. Barber has faithfully served as pastor of Greenleaf Christian Church in Goldsboro, NC. Appropriately named, Greenleaf under Barber’s leadership has itself been a transformational powerhouse in a small community. No surprise there.

The Third Reconstruction: Moral Mondays, Fusion Politics and the Rise of a New Justice Movement

Rev. William Barber

Beacon Press

(January 2016)

In the book, Rev. Barber insists that an honest pastor must also be a prophet: that it’s not enough to try to heal the people’s wounds without also naming the source of the wound as racial and economic injustice. He gives us the useful phrase “attention violence” to describe the blinders that too many pastors and laypeople choose to wear in order to block out disturbing social realities. He walks his readers through his own theological formation, citing Juergen Moltmann’s precept that peace with God must entail conflict with the world and astutely critiquing both Reinhold Niebuhr’s realpolitik and Stanley Hauerwas’ overemphasis on an inward-looking ecclesiology. Barber is especially good on Hauerwas and on the unreliability of the church in regard to understanding and living out its prophetic calling.

Rev. Barber describes himself as a theological conservative in contrast to the “liberals” who have freely ignored the Bible’s main message of liberation while obsessing about the snippets they take out of context to beat up on people of color, women and gay people. He objects, passionately, to the appropriation of the word “evangelical” for a worldview that is utterly devoid of prophetic critique. He reminds us, eloquently, about the important historical linkages between American evangelicalism and social regeneration: abolition, temperance, women’s rights and labor rights.

Barber gives us good insights into how First Reconstruction fusion politics actually held on in North Carolina for a very long time in the face of an increasingly militant Jim Crow repression, not finally succumbing until the very end of the 19th century. In fact, the Moral Monday movement’s very public challenge to the 2012 Republican putsch in Raleigh was grounded in the still-extant Reconstruction-era clause in the state constitution that allows citizens to address their legislators directly.

He insists that the work we all need to be about is primarily cultural and not “political” in the usual sense of the word. Our job is to avoid abstractions and put the everyday people and their suffering front and center in the discussion: the very opposite of “attention violence.” And he teaches that fusion politics doesn’t mean that every member of a broad coalition has to agree fully about everyone else’s issue. What is necessary is simply that every member have every other member’s back, so to speak.

This approach seems to be working in North Carolina and elsewhere. Up in some of the mountainous regions where black people are relatively thin on the ground, white people are organizing and joining NAACP chapters.

I recently had a conversation with Rev. Barber on the “Third Reconstruction,” the meme on the lips of many progressives around the country these days.

Is “Third Reconstruction” exactly the right framing for what is needed now in view of the fact that the first two Reconstructions were fairly thoroughly crushed by white reactionaries?

Good question. What we tried to lay out in the book is that this language is historically important. No “two words” are exactly the right framing for what is needed now. We use the Third Reconstruction framework to remind people of the history of the two temporarily successful moral fusion movements in the South that fundamentally changed the nation. “Reconstruction” names a time when blacks and whites in the 1800s found a way to stand together grounded in our deepest faith and constitutional principles and changed the language and the law for the purpose of justice. Without this fusion there would have been no 13th, 14th or 15th amendments. There would have been no Civil Rights Act of 1875, no union between the women’s suffrage movement and the struggle for black liberation. Without understanding the power of this movement, you can’t understand the violent backlash, the economic isolation and the judicial retrogression that followed.

The truth is that black people in North Carolina had more political power in 1868 than they did in 1968. We had more political power after the Voting Rights Act in 1965 than we do today after Shelby.

In the 1950s and ’60s, it was again fusion politics that led to a Second Reconstruction. Blacks and whites, Jews and Catholics, labor and youth came together. Without this fusion we can not fully understand the fight that led to Brown vs. Board of Education, the expansion of social security, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the March on Washington, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Freedom Summer, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the Movement’s stance against Vietnam or the Poor Peoples’ Campaign. But we also cannot understand why there was a violent backlash, the development of the white Southern Strategy, and how “cutting taxes,” “entitlements” and “states’ rights” became such potent, racialized language to persuade people to vote against their own self interest. Because we don’t know this history, we don’t understand how public faith was hijacked and narrowed to only include abortion, criticism of homosexuality and the fight for prayer in schools as “moral issues.”

So I choose to use the language of a Third Reconstruction to suggest that now is the time for a third act of faith—a third moral fusion movement in the South. Without remembering Reconstruction, we too easily think of American history as having this terrible sin of slavery at its beginning, then getting a little better with Jim Crow and a little better with civil rights. It’s too easy to say, “No, things aren’t perfect, but we’ve come a long way.”

We cannot dismantle what we have not named.

The truth is that black people in North Carolina had more political power in 1868 than they did in 1968. We had more political power after the Voting Rights Act in 1965 than we do today after Shelby. Unless we face the fact that America’s first two Reconstructions were undermined by the monied elites of plantation capitalism, we can’t even name the challenge we face today.

In seeking a higher moral ground, we must break out of dead-end racialized framing. We must intentionally challenge the ahistorical and amoral tendencies that many public intellectuals–black and white–fall into when the historical and moral challenge of our time is raised: how to dismantle the system of racism. We cannot dismantle what we have not named. Our attention to the language of Reconstruction is a direct challenge to those who cry, “You are playing the race card” whenever anyone dares to name the continuing reality of entrenched structural racism. At the same time, it helps us remember how fusion coalitions have created spaces of interruption in our long history of racial injustice. These concrete victories in Movement history give us hope to say with Langston Hughes, “America never was America to me / and yet I swear this oath / America will be!”

You counsel us to follow the money in respect to what the Right is up to, but in 2016 we know that vast “black pools” of anonymous money will be in play. Does this development not represent a whole new level of challenge to those trying to restore democracy and reclaim a common good ethic?

With love, I suggest the word “secret” is more accurate than “black” when talking about the billions of dollars being spent to buy candidates’ souls. Of course, secret pools of money buying Southern elections is a problem. SCOTUS’ Citizens United decision changed the rules of the game, making it easier for big money to play partisan politics. As John Nichols has said in his book, we are more and more a “dollarocracy.”

But we remind our progressive friends who are not up on their Southern history: Poor and jobless people of all races have never had money. That’s the definition of “poor.” But if Harriet Tubman could lead hundreds of slaves to freedom with nothing but the North Star, moss on the trees, a pistol strapped to her leg and faith in her heart (despite lack of resources and epilepsy), then today we ought to be able to use the Internet, Twitter, Facebook, cell phones and our growing network of churches to educate the new Southern Electorate—black, white, Latino, Asian, gay, straight, labor, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, agnostics, atheists, atudents and their elders, environmentalists—all who want a better life for all God’s people.

The South matters because it is the native home of America’s original sin.

Yes, we must fight Citizens United and its fallout in the courts. But the Movement that is growing in the streets tells a different story. At the same time that those who want to hold onto power are retreating behind a veil, folk who struggle to survive in minimum wage jobs are reclaiming the public square in the #FightFor15. Women and men who’ve disappeared in America’s gray wasteland of mass incarceration are taking back the streets, insisting #BlackLivesMatter. In the Moral Movement, people who’ve been directly affected by legislatures’ refusal to expand Medicaid in the South are exercising their constitutionally protected right to instruct their legislators. At the same time democracy is attacked by the Court, it is getting born again in the state house and in the streets. We know from experience that when fusion coalitions build a Movement that sticks together, no amount of money can stop us.

Along with many others, you argue that the South is the place where the long-delayed revolution of values that Dr. King talked about can finally be realized. Say more about that. We know you don’t mean to say that nothing can be done in the Rust Belt states where deindustrialization has gutted the white middle class. What is the special significance of concentrating on the South?

No, a Third Reconstruction isn’t only about the South. But it must be rooted in the South and its story. It must learn the lessons of our history and tap the wisdom of the Southern freedom struggle. And this knowledge will impact the entire nation.

The South matters because it is the native home of America’s original sin. The sin of white supremacy, slavery and intentional legalized racism has plagued the heart and soul of America from its beginning by creating structures of institutionalized discrimination and disenfranchisement. The plantation economy was established in this place. For that very reason, it is also the birthplace of America’s moral imagination. The American prophetic black church tradition was born in the South’s brush arbors. Even Jefferson’s “we hold these truths to be self-evident” grew out of his own tortured struggle with the realities of black life in the South. From Montgomery’s bus boycott to Selma’s “Bloody Sunday,” America has been born again in the South, with each struggle we see a kind of rebirth.

The South’s moral imagination has been the seedbed of Movements that changed America. The abolitionist struggle, which brought together a broad coalition, was focused on the South. After the Civil War, fusion politics emerged in Southern states as a concrete form of shared life across the color line, guaranteeing public education, labor rights and full citizenship for all. Though Dr. King and others were absolutely right that the Movement had to go North in the late ’60s, it’s still significant that the struggle was rooted in the South.

The Southern Strategy, which was developed by Kevin Philips, posited that Republicans could lock up the South by appealing to old racial fears without using race-specific language. Rather than saying “segregation,” they started talking about “entitlement programs,” “busing” and “law and order.” Divide-and-conquer politics broke up the coalitions of the Second Reconstruction and so-called progressives have accepted this as a given.

Yes, San Bernadino was terrorism. So was Mother Emmanuel AME. So are the drone attacks on civilian homes in Afghanistan. So is the carpet-bombing of cities.

But we have empirical proof that the Southern slave and Jim Crow states, where the great majority of African Americans and many Latinos live, are ripe for a new Southern Human Rights Moral Strategy. This new demographic in the South feels a deepening need for relief from the pain caused by extremist politicians who vote against the interest of the very people who elected them because they have been conjured by the Southern Strategy. A majority of the South’s gubernatorial and legislative leadership is stuck in an historic time lock, bought by big money.

In my home state of North Carolina, for instance, Governor McCrory’s denial of Medicaid expansion directly impacts half a million people, 346,000 of which are white—and mostly Republican. There are over 160 electoral votes in the South, held captive by the strategy of regression. The moral fusion movement we are a part of is based on repairing those breaches. And it will not be stopped, unless we stop. Yes, the extreme racists will scapegoat the outcasts. But the more they expose their politics of hate, fear and discrimination, the more the politics of love, courage and justice seems preferable to the masses. We have seen in North Carolina’s Moral Movement that the moral imagination of the South is still alive. Fusion coalitions are still possible. Indeed, the moral argument is the only argument that has the capacity to offer us a hope and future.

You write that we can still be “greater than the sum of our fears,” but never before have Americans been quite as fearful as they are today, thanks in part to actual threats and in part to the effective fear-mongering of some opportunistic politicians. How can progressives help to calm these fears as part of our organizing work?

Nothing is gained by pretending there aren’t terrible things to be afraid of. Terrorism is real because millions of people live in terror. But we must be clear about the root of this terror. We cannot misdiagnose the malignancy of terrorism. It is not Islam. It is not “foreign.” Terror is an American export because it is rooted in our heretical notion that some people don’t matter as much as others. The greatest terrorist attack in American history was the series of race riots that killed thousands of black people from Springfield to Tulsa to Wilmington in the late 1890s and early 1900s.

Yes, San Bernadino was terrorism. So was Mother Emmanuel AME. So are the drone attacks on civilian homes in Afghanistan. So is the carpet-bombing of cities. We must not forget that the key leaders of Daesh met and developed their agenda in the U.S.-run prison at Camp Bucca in Iraq. And if we are going to talk about violence and terror, we must not forget the wisdom of the late Coretta Scott King:

Poverty can produce a most deadly kind of violence. In this society violence against poor people and minority groups is routine. I remind you that starving a child is violence; suppressing a culture is violence; neglecting schoolchildren is violence; discrimination against a working man is violence; ghetto house is violence; ignoring medical needs is violence; contempt for equality is violence; even a lack of will power to help humanity is a sick and sinister form of violence.

If the reality is that millions of people live in terror for good reason, what can drive out fear? We say “fusion friendships.” I grew up fearing white people for good reasons. When I was twelve years old, my uncle gave me a shot gun and told me to shoot anything that moved when the Klan came to burn a cross in his yard. But I wrote this book with a white man I met 20 years ago when I was working for a Democratic governor, and he was working for a Republican Senator. We know something beyond our fear because we’ve experienced it in fusion coalitions. This community and trust building takes time, but it is the essential work of democracy. It’s the essential story of Moral Mondays that no newspaper was able to tell.

The late Manning Marable asserted that the power of white supremacy rests on more than organized money—that it also rests very significantly on fraud and force: fraud in regard to suppressing or twisting the truth of our sorrowful history, and force in regard to the continuing torture and abuse of black and brown bodies. In your book, you don’t talk about white supremacy very much except by implication. Can we triumph over this toxic legacy without naming it clearly?

You’re absolutely right. We cannot miss this fact. But it’s there in the book, even if we don’t use the language of “white supremacy” often. We’ve laid out a plan to take on white supremacy, thereby unmasking it and pointing us to higher ground. We look at public policy through a moral lens of justice for all and through the constitutional principle of governing for the good of the whole. Our work points out how these extremist policies are morally indefensible, constitutionally inconsistent and economically insane. We are challenging the position of the religious right that the preeminent moral issues today are about religion in public schools, abortion and homosexuality with a critique that says the deepest public concerns of our faith traditions deal with how do you treat the poor, those on the margins—the least of these, women, children, workers, immigrants and the sick.

Jim Crow went to law school and came back as Mr. James Crow, Esq. He likes to pretend he is not as violent.

Rooted in hope, not fear, we bring together a diverse coalition that takes seriously the issue of race. This is a movement that was born in the South, and we cannot afford to be ahistorical. Anti-racism and anti-poverty must be at the heart of our struggle. We understand that organizing the changing demographics in South—the increase in black and Latino voters and the increase in young voters who vote their futures, not their fears—is connected to the extremist attack we are facing.

“White supremacy” was, in fact, the language that was used to describe the backlash against the First Reconstruction in North Carolina, where the only successful coup d’état in U.S. history happened in Wilmington in 1898. The Democratic Party ran an explicit white supremacy campaign in 1898. But “fraud and force” is a fair description of the backlash against fusion organizing in every age. And it is what we face today. Yes, Jim Crow went to law school and came back as Mr. James Crow, Esq. He likes to pretend he is not as violent. But the violence of policies passed in our state house killed over 4,000 North Carolinians this year—more than ISIS killed worldwide. We are challenging the fraud of gerrymandered voting districts in court, and we have received our fair share of death threats. So, yes, Marable is right. “By any means necessary,” is certainly the modus operandi of monied elites past and present. And they don’t even have to be white men any more. Still, we will fight them and we will win.

What are we fighting for?

- Secure pro-labor, anti-poverty policies that insure economic sustainability by fighting for employment, living wages, the alleviation of disparate unemployment, a green economy, labor rights, affordable housing, targeted empowerment zones, strong safety net services for the poor, fair policies for immigrants, critiques of war policies that further hinder our ability to have a real war on poverty, infrastructure development and fair tax reform

- Educational equality by ensuring every child receives a high quality, well-funded, constitutional, diverse public education as well as access to community colleges and universities and by securing equitable funding for minority colleges and universities

- Healthcare for all by ensuring access to the Affordable Care Act, Medicare and Medicaid, Social Security and by ensuring environmental protection and women’s health

- Fairness in the criminal justice system by addressing the continuing inequalities in the system for black, brown and poor white people, and by resisting the proliferation of guns

- The protection and expansion of voting rights, women’s rights, LGBT rights, labor rights, religious freedom, immigrant rights and the fundamental principle of equal protection under the law.

You have demonstrated that a fusion movement can bring dozens of disparate groups together in common struggle. Many involved in progressive organizing have noted that the way organizing projects are funded actually militates against shared fusion agendas in that the funders these days make grants that are very narrowly focused on specific issue areas. The grantees in turn tend to stay within their silos. Do you have any word to share with the philanthropic world in regard to this problem?

I’d say to them what I say to everyone in the Movement: Be open to the Spirit moving us in new ways. Recently I was in New York City to receive an award from a philanthropist. After I’d received the award, this 90 year-old elder’s son invited me to walk to where his dad was seated as he has some difficulty walking these days. But he insisted upon getting up and grabbed my hand with great passion. “I’m so glad to be giving my money this year to a Movement that I know is making a difference,” he said.

Sure, we must make the best plans we can. But I think every funder wants what that man wants. When we started the HKonJ People’s Assembly Coalition in North Carolina ten years ago, we didn’t have any money. In so many ways, that was a gift. We started with 14 groups (we now have over 200). Our lack of resources forced us to come together and focus on the gift of one another. We learned to be nimble and quick. We figured out what worked, and we kept doing it because it was bringing us closer to what we all wanted.

We say to every funder, “Give not so we can do something but so we can keep doing.” It’s a different ask. A Movement is afoot. Even now, I’m joining Jim Forbes on a Moral Revival tour across the nation. We have a vision, and we believe the provision will come. We don’t have money; we have a mandate. The nation’s soul is at stake. People are dying, and we know we must show a way beyond the limited left/right debate that is too puny for the times in which we live and the future we desire.

If I could say one thing to funders, I’d say, “We must invest in a Movement, not a moment! We need an indigenously led, state-based, state-government focused, deeply moral, deeply constitutional, anti-racist, anti-poverty, pro-justice, pro-labor, transformative fusion movement. We need transformative fusion coalitions where relationships with coalition partners are transformative, not transactional, because we understand the connectivity between the issues that each partner focuses on and embrace them as our own. We must build relationships that are long-term, not based on one issue or campaign. The greatest myth of our times is that extreme policies only hurt a small subset of people, such as people of color or the poor. These policies harm us all.

I’d say this: Think long term. Don’t worry about short-term victories. Don’t just fund electoral strategies; fund transformational movements. Let’s not forget that’s what Charles Koch decided to do in the 1970s. In many ways, it worked.

This is the most forgotten admonition of Dr. King’s dream. What did he say to the people who came together for the March on Washington? He said, “Go home!” Go back to Georgia and Mississippi, to North Carolina and Tennessee. Go home and build a Movement that can change this nation. That’s a strategic plan for progressive foundations: Fund people and organizations that are building the movement that looks like the America we want to be. You may not get there with them, but we will get there if we keep moving forward together, not one step back.