I plead guilty right up front to once participating in the cult I intend to critique. I, too, have worshipped at the feet of the Great Emancipator, imbibing in my early youth the whole kit-and-caboodle of Lincolnian mythology.

My people were “Party of Lincoln” Wisconsin Republicans. We read our Carl Sandburg, we memorized the Gettysburg Address, and we identified with the rough-hewn Nobody who rose to become a real Somebody, almost godlike in his towering moral majesty. Sure, we were also fed the usual pap about George Washington’s flawless character, but our sense of who this Washington was remained distant and blurry. We already knew that GW’s story had been carefully burnished beyond credibility. E.g., we knew that the attributed line, “I cannot tell a lie,” was itself a lie.

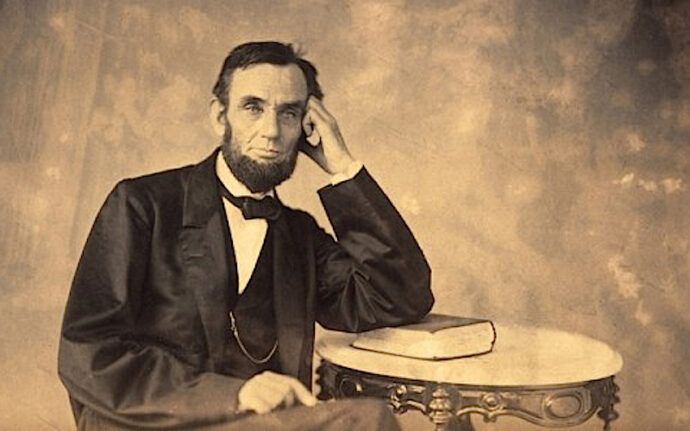

But Mr. Lincoln was different. He was much closer to us in time, obviously: my immigrant great-grandparents were around to witness his rise, his struggle, and his martyrdom. And this rangy, rail-splitting Abe was down-to-earth in a way the alabaster Cincinnatus of Mt. Vernon could never be. We heard it said that Lincoln could tell a funny story; we later learned that he could also tell a bawdy story—and we liked him better on that account.

To mark this week when Lincoln’s Birthday is celebrated, The New York Times Book Review splashed a sketch of the stovepiped Great One on its cover and featured reviews by Jill Lepore and Drew Gilpin Faust (Fight Fiercely, Harvard!) of three new Lincoln books.

Lepore’s review of Martha Hodes’ Mourning Lincoln and Richard Wightman Fox’s Lincoln’s Body is exceptionally penetrating. My thinking here about Lincoln’s religious significance was triggered by the always-shrewd Lepore’s observation that Lincolnolatry remains very much alive AND that it still obscures our appreciation of the bottom-up revolution that made Lincoln do the one thing he didn’t particularly want to do: commit to the freedom of millions of enslaved human beings.

Lepore ends her review with this extraordinary apercu:

Abraham Lincoln was the best president the United States has ever had. But we live inside his tomb. For a very long time now, too many Americans have found it easier to think about Lincoln’s body — that brawn, that bullet — than about the bodies of the millions of men, women and children who had been kept in slavery, bodies stolen, shackled, hunted, whipped, branded, raped, starved, murdered and buried in unmarked graves. The mourning of Lincoln has come at the expense of mourning them.

“We live inside his tomb”: I wish Lepore had added that we also live within the nimbus of this man’s resurrected glory, in no small part because the rapid enactment of Amendments 13-15 has often been construed to be Lincoln’s posthumous triumph, just as the crazy reports of Christ’s resurrection were construed by the Galilean’s stricken followers to represent divine vindication.

In fact, in the standard version of American history (the one told of white people, by white people, and for white people), there are actually two related martyrdom/resurrection stories associated with the struggle against Plantocracy: John Brown’s and Abraham Lincoln’s.

Many Abolitionists, Henry David Thoreau included, treated Brown’s hanging on Dec. 2, 1859, as a kind of Crucifixion and offered flowery encomiums about someone most of them had taken pains to distance themselves from until he was safely dead. (Brown’s hanging was witnessed by John Wilkes Booth, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Walt Whitman, among others).

In death Brown instantly became a larger-than-life figure: in the South a frightening golem, and in the North a fiery prophet at the very least, if not quite at the Jesus level (some hadn’t forgotten his Kansas butcheries). Even before the outbreak of the Civil War soldiers in the North were singing “John Brown’s body lies a-moulderin’ in the grave! His soul goes marching on!” The improvised reference to Brown among the uniformed ranks took place prior to the publication of Julia Ward Howe’s “Battle Hymn,” which she decided to set to the same thumping hymn tune.

Five years later Brown’s resurrected glory was naturally eclipsed by the much greater resurrected glory of an already-lionized wartime president who would be struck down on Good Friday by the villainous Booth. Whitman might have mourned the death of the strange and always-ferocious Brown, but he gave his whole heart to his slain “Captain” in poems that still resonate.

The two books Lepore reviews both document and magnify the particular unsurpassed awe and reverence that attended and still attends the subject of Lincoln’s death: the intensity of the public grieving, the oratorical effusions, and the 12-day procession of the casket by rail through New York City and then slowly on to Springfield.

As Lepore writes, it is the very stuff of legend—and dangerous legend. It leaves in place the mistaken but still very widespread notions that Father Abraham was somehow moved by compassion to free the poor defenseless slaves and that bringing release to the captives was in fact a primary part of Lincoln’s presidential ambition.

Neither is the case; the so-called Emancipation Proclamation was issued very cautiously and of necessity as a limited military measure. As well, Lincoln never campaigned or governed on an emancipation platform; like many others of his time and background, he initially believed that Black people should be re-colonized in Africa. Even after coming to support a degree of legal equality for Blacks, Lincoln never believed that Blacks could be the social equals of whites.

The redeeming thing about Lincoln (and it’s hard not to compare Lyndon Johnson’s odyssey 100 years later) is that at least he could be made to bend and made to grow in his understanding of the moral claims of others, notably of Black others. But possessing such an important redeeming quality is not the same as being The Redeemer, and the muddling of this difference is where our obsessive devotion to Lincoln (including Barack Obama’s obsessive devotion) has taken us.

Lincoln achieved greatness due to the struggles of others: the struggles of Black people first and foremost, but also the struggles of determined white Abolitionists who were always few in number and always weak in conventional political terms but whose impact was convulsive and ultimately decisive. A lesson for these times? Look to the roots and to the so-called margins for the real transformational energy. Respect, but don’t revere, your sainted leaders of legend.