As the rhetoric of the Russian Orthodox Church grew even more shocking and dangerous this week, an anonymous group of students at the famed St. Sergius Orthodox Theological Institute in Paris have sent a letter asking their local bishop, Metropolitan John (Reneto), to leave the Moscow Patriarchate—led by Putin crony Kirill—for the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Constantinople which opposes the war. It’s been confirmed to RD by sources close to the student group that the letter has indeed been sent.

The Institute is in a similar political and cultural situation as St. Nicholas in Amsterdam, the famed Russian Orthodox parish that broke away from Moscow last month after its pleas to Patriarch Kirill to end the violence in Ukraine were met with retaliation, both online and in real life. It’s worth noting that St. Sergius has only recently become part of the Moscow Patriarchate. For most of its history, until 2018, it was under Constantinople, when it was handed over to Moscow as a (clearly unaccepted) consolation prize for an independent church in Ukraine. This is important, because it does beg the question of whether or not St. Sergius would have in fact ever been as vibrant and important an intellectual center if it had spent its whole life under Moscow.

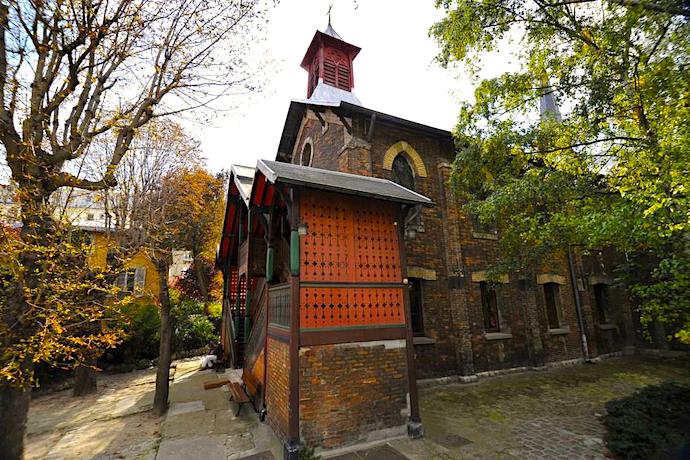

Founded in 1925, St. Sergius is the oldest Orthodox theological school in the West and holds a unique and storied place in the history of not only 20th-century Orthodox academic theology, but of Orthodox Christianity’s larger engagement with Western modernity. The Institute is the child of the post-Revolution Russian émigré community in Paris and has been the intellectual home of some of Orthodoxy’s most important and (if the term has meaning in this deeply conservative and tradition-bound world) modern thinkers, among them Father Alexander Schmemann, who was both a student and teacher at the Institute.

In 1951, Fr. Schmemann came to the United States to teach at St. Vladimir’s Theological Seminary. The seminary (known as St. Vlad’s to virtually everyone), like St. Sergius, was founded by refugees from the Bolsheviks and is the second oldest Orthodox seminary in the United States, second only to the Greek Orthodox-run Holy Cross Theological School which began the year before. While St. Vlad’s was already in its second decade by the time Fr. Schmemann arrived, it is not incorrect to think of it as “the house that Fr. Schmemann built.”

He became Dean in 1962, a post held until his death in 1983. During the 21 years of his deanship, Fr. Schemmann published some of the most important Orthodox theological treatises ever written in English. Among them was the highly-influential For the Life of the World, a reflection on liturgical worship and Christian faith.

As an adjunct professor at a number of non-Orthodox seminaries, as well as one of the first preeminent Orthodox theologians to write and publish primarily in English, Fr. Schmemann was critical in introducing Orthodoxy to America—and, importantly, in introducing America to Orthodoxy.

Fr. Schmemann’s life and theological work are a testament to an open kind of Orthodox Christian theology and faith, the very kind of expression of Orthodoxy that is being challenged (and one could say, intentionally dismantled) by Kirill and his allies. If Fr. Schmemann’s deanship at St. Vladimir represented the possibility of Orthodox Christianity enjoying a thriving and intellectually robust life in the modern age, the patriarchate of Kirill represents the renunciation of that possibility.

Because today, Fr. Schmemann’s legacy at St. Vlad’s is under serious threat, and his legacy can be viewed as a bellwether of American Orthodox Christianity. The seminary has come to be dominated by ultra-conservative American converts from various Protestant denominations, largely part of the wave of Protestant conservative Culture Warriors into the Orthodox Church that began in the 1980s. They have mostly succeeded in turning the school into a fortress in their on-going battle against the forces of modernity.

When the school isn’t hosting ecumenical dialogue between the Orthodox Church in America (the Orthodox jurisdiction that oversees it) and the conservative breakaway Anglican Church in North America, it is hosting Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev), the ultra-conservation Russian Orthodox bishop who has his eyes on being the next Patriarch of Moscow, and a man who once said that women who are victims of domestic violence shouldn’t discuss their abuse in public because, “discussing these issues one way or another is propaganda for sin” (importantly, St. Vladimir’s invitation came two years after these remarks).

Notably Metropolitan Hilarion has, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, been stripped of his professorship at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland, though St. Vlad’s has not returned the $250,000 it received from an anonymous donor to establish The Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and all Rus’ Endowment for Biblical Studies, right around the time of Metropolitan Hilarion’s lecture last year.

Which brings us back to St. Sergius. When the seminary was transferred to the Moscow Patriarchate from Constantinople, there was some suggestion that it would be left alone, merely to be used by Kirill and his allies against charges that they were totalitarian reactionaries; a token jewel of free thought in the tsar-like crown of Moscow. And this has, for the most part, been true. But, like so many tenuous situations in the Orthodox Christian world, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has rendered this situation no longer tenable.

Orthodox Christian seminaries and theological schools are a relatively recent and still quite rare phenomenon in the West. As such, they serve as important locations for dialogue between the West and the Orthodox Christian world. Guarding their moral and intellectual integrity should be of utmost concern. There’s an argument to be made that St. Vladimir’s has already been lost in this battle. If St. Sergius is lost, the hope for a healthy, pluralist, democratic Orthodox Christianity, in America and beyond—one that acts as a counterweight to the authoritarian strain preferred by the Moscow Patriarchate—will take another blow. And that is a possibility that simply cannot be allowed to come to pass.