When I heard the news that R.E.M. was hanging it all up, my first impulse was to call my wife and teenage sons, to commiserate and reminisce together about our shared experience of a collective, four-man; someone that felt like a part of the family. It was precisely the kind of instinctive response you have when you learn of an unexpected death or a national tragedy: connect quickly and viscerally with those you love, and start processing the sudden end of a narrative whose final episode you hadn’t seen coming.

For someone captivated in the ‘80s by the complexity of front man Michael Stipe’s portrayal of a triumphant negotiation of existential crisis in “Losing My Religion,” one of MTV’s most popular music videos of all time, it was an oddly trite religious response: seek emotional refuge, collectively craft a narrative, and give memory free rein to mine meaning out of meaninglessness. On the very day that the state of Georgia, who also gave us R.E.M., conducted a brutally cold execution as the world looked on in disbelief, nothing might have seemed more insignificant than the retirement of a few wealthy, successful rock stars.

But maybe it was a response fully in line with the band’s often unspoken religiosity. Take that video, for example [scroll down to watch]: has there ever been 4 minutes of pop culture as spiritually powerful as the anguished Stipe mourning his loss of faith while doggedly, resolutely affirming, well… something? As his religion slipped away to the accompaniment of Peter Buck’s mandolin, he danced a set of steps that will forever cement Stipe’s image for a generation raised on MTV, while capturing personal spiritual crisis with an emotional depth and precision that are uncanny. Stipe is, in those few seconds, at once transported but unconvinced by the experience.

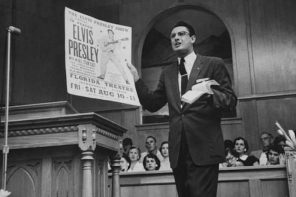

At other moments, R.E.M. quietly developed a theological repertoire for the disillusioned who still wanted to believe. They struck a supremely understated moral tone, lampooning the absurdity of the Reagan era and the absence of anything approaching a compelling social or political vision with the subtlest of parody (“what’s the frequency, Kenneth?”); they raged against an epidemic of personal alienation that drove the likes of Andy Kaufman to suicide, while fondly recalling that goofin’ on Elvis was the sublime, if tragic, product of losing touch. Somehow, while America was going to hell all around us, R.E.M. hung in there and showed what it might mean to stand up to an accelerating debasement of our national culture without giving in to cynicism. They could point to the transcendent and express the frustration of a generation robbed of the cultural resources to grasp it without ever trivializing our national spiritual malady by crassly naming it.

Last week also marked the twentieth anniversary of Nirvana’s grunge classic, Nevermind. Juxtaposed against R.E.M.’s complex and ambivalent assessment of person and society in the late 20th century, the despair of that album reads like a furious admission of the impotence of its own protest against a culture and politics corrupt to their core. Just as R.E.M. will always be the source I credit for my kids’ awakening to the artistry and moral challenge that rock music at its best can deliver, Nirvana will provide the soundtrack to the fading images of one friend after another lost to the heroin that hit the alternative music scene in Atlanta as Nevermind hit the charts. Could anything be further from the nihilism of Nirvana’s distorted and driving chords than R.E.M.’s qualified insistence that the articulation of meaning and the comfort of community are our best hope in troubled political times? Thanks, fellas, for keeping the faith.