Not too long ago I received the following text:

I’m gonna guess that your question isn’t about evolution, per se, but about what happens when religion appears to put us at odds with evolution. If modern humans had numerous ancestors, and relatives that lived alongside us, but reached evolutionary dead-ends, then what do we do with an actual Adam and literal Eve?

I’ve an answer that might help modern Muslims like us come to terms with what we know of our biological ancestry—and, incidentally, might open the door to dealing with the existence of intelligent life somewhere out there. Because if Allah created aliens, we should totally be ready.

At least theologically.

Lucy in the sky with diamonds

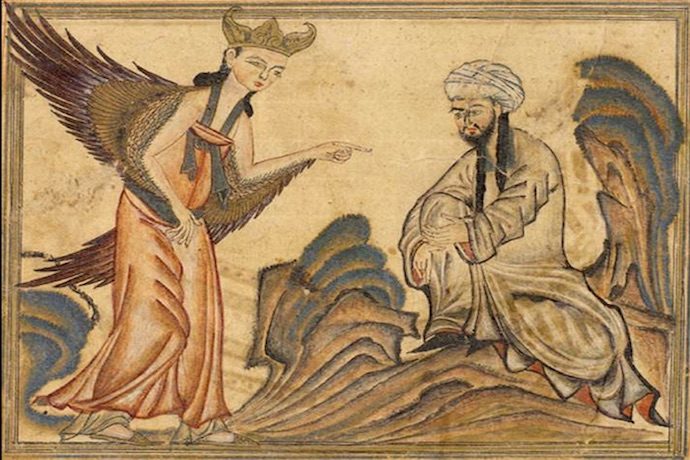

In the Islamic conception, Adam’s the first Prophet chosen to preach to humanity, but he and his wife Eve are also the first in a new species, chosen to be God’s Caliphs—like “representatives”—on Earth.

But if we believe that, how do we deal with Neanderthals—was Adam their ancestor, too? Do Adam and Eve fit somewhere differently on the family tree? Or are modern humans somehow distinct from species we’re clearly so similar to?

When I’ve raised such questions, I’ve gotten different responses. Some Muslims argue that if the Qur’an doesn’t go into detail about the origins of the world, or human life, then that’s because God wants us to focus on the moral meaning. The science was left for us mere mortals to divine.

Others have proposed that Adam was an archetype for humankind, not a person; that huge chunks of time passed between the forbidden fruit and their Earthly exile; that the Adam in heaven wasn’t quite the Adam on Earth; or that while Adam was created out of the same genetic stuff as life on this planet—how else could we survive?—that genetic similarity doesn’t imply direct ancestry.

We only appear to be related. Part of us is similar to earthly life. Part of us (our soul) is altogether heavenly. I don’t know of course if any of these will satisfy you. Perhaps an apparently offhand remark in the Qur’an might.

The why and the mighty

Islam’s Genesis is pretty spare, in typical Qur’anic fashion (beginning at 2:29), emphasizing moral and spiritual themes, while mostly avoiding background information, like timelines or lineages. To an audience of angels assembled before Him, God announces, “I am creating a Caliph—on Earth.”

Then He makes and places Adam in a garden instead. (Weird thing #2.)

Before God even gets to Adam, though, the angels ask a very provocative and very unexpected question. “Will you place upon the Earth one who corrupts, and spills blood?” (This would be weird thing #1.)

God’s cryptic response? “I know, and you don’t.” He doesn’t ever really answer, in fact—at least not directly. Maybe it’s meant to echo down to us, a question we must constantly pose to ourselves, to see if we are in fact what the angels were worried about. But why would they know to be concerned?

If you said to me, “I’m gonna buy a house,” and the first thing out of my mouth is, “Will you buy a house with a leaky roof, and a flooded basement,” a reasonable assumption would be that you’d previously bought a house you shouldn’t have.

God is in the middle of an important announcement, the creation of the very species for which the Muslim scripture is intended as moral guidance, and the angels all but kill the moment, rain on the parade, ruin the surprise, and that’s that. The Qur’an never returns to this subject again, which is curious. Makes you think, doesn’t it? It makes me think about aliens.

In space God can hear you scream

Maybe you heard, a while back, that Saudi Arabia was training its religious police to fight “black magic,” “magicians” and “sorcerers.” Well that’s because plenty of folks in the Muslim world do believe in such things happening in our human world, though it’s often not humans behind it.

And before you get all high and mighty, lots of Icelanders believe in elves.

My point being, Islam has no problem with intelligent non-terrestrial life: God is not human, is perfectly omniscient, and is not only not on Earth, but has no location in space or time. Angels are sentient but have no free will. They can question God—as above—but they can’t act on their doubts. There’s another sentient, “rational” species, too, this one with agency. The jinn, of whom Satan’s the most famous.

Satan had been worshipping God for God-knows-how-long, and instead God created an entirely new being, Adam, to be His Caliph. The elevation of a new, untested, unproven, and plainly inferior species—there’s a reason why jinn have entered popular imagination as magical “genies”—was the snub to end all snubs. A sulking Satan convinced Adam and Eve to eat from the Tree, disobeying God. That’d show God that Adam and Eve were not Caliph material!

But it backfired.

In marked contrast to Satan, Adam and Eve were sincerely contrite, they asked for forgiveness—Satan never did—and were forgiven. They were exiled to Earth, however, but it was on Earth, remember, where they were supposed to be Caliphs. The whole thing was like a science fiction episode in which Satan ended up causing the very thing he’d set out to make impossible. The Qur’an makes clear that jinn will be held responsible for their actions, but only humans receive revelation. If a jinn lived at Jesus’ time, she’d have to follow Jesus. If a jinn lived now, then Muhammad is the Prophet to be heeded.

But how would Islam deal with life beyond God and man, angels and jinn?

The Qur’an insists Muhammad isn’t just the final Prophet for humans and jinn, but “a mercy to all the worlds.” The discovery of intelligent life, say on Titan, would provoke some very tough questions. If the Titans didn’t have Prophets, why would God leave them in the spiritual darkness? If the Titans did have Prophets, would their Prophets be exclusively theirs and our Prophets our own? If so, then is Muhammad still “a mercy to all the worlds”—does that mean Muhammad’s teachings would counsel us to treat all with kindness and decency all those we encounter, whatever planet they might be on?

Isn’t Muhammad, as Muslims believe, the best of all creation? As you can see, I spent a lot of time in the library as a kid. But I’m not pulling this out of thin air.

Battlestar Islamica

When the angels asked God, “Will you create someone who corrupts, and sheds blood?” maybe they meant the jinn. That doesn’t add up, however: Satan was a jinn so pious he worshipped where only angels genuflected. In which case perhaps these angels were comparing the looming Caliph to earlier forms of human life, who’d been made for the same task, but failed.

Maybe they’d killed each other off, or were still alive, but behaving badly. Maybe there were many candidates for Caliph, and these included life somewhere else, Caliphs for other planets or places. Aliens. Who’d performed rather poorly on the political transparency and violent crime index—the angels present a rather Nordic barometer of success here—which explains why, when God announces a Caliph, they’re skeptical. Which is to say, there’s room for new perspectives.

Sacred texts don’t have to change. The meanings we find in them do. Because we do. We don’t have to believe religion and science are necessarily at odds; there was a time when Muslims were known for their enthusiasm for empirical research, curiosity and discovery. Which way would Mecca be on the dark side of the moon? How would Ramadan work on Venus, where each day is many months long? Would Plutonian colonists have to perform the pilgrimage to Mecca or die trying? We don’t have to answer these questions, of course, until we need to.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we got to a point where we had to?