Modern atheism has a PR problem.

For too long, the most outspoken non-believers have been antagonistic, bombastic, and sometimes profoundly embarrassing older white men. When they aren’t writing inflammatory books, these men interrupt people on talk shows and get into Twitter fights with teenagers. They model behaviors that seem to alienate their fellow non-believers as much, if not more so, than religious people.

There’s space for a more diplomatic approach. With that in mind, a new app called Atheos aims to help non-believers have friendly, thoughtful discussions with people of faith.

The app can be a bit silly, and its tone toward believers can be condescending. But Atheos appears to be part of a good-faith effort to inject civility into conversations between believers and non-believers. The app may not convince many people to become atheists. But that’s not the point. Instead, at best, Atheos is an instructive tool for non-believers to reflect on their own positions more critically and thoughtfully.

Atheos is structured as a gamified set of questions and answers inspired by the Socratic method. Users open the app and make their way through “Cave Levels,” each of which present you with hypothetical scenarios, discussions, and encounters with people of faith. At each conversational juncture you have to select the best answer to the hypothetical believer’s challenge or query. This allows non-believers to practice discussions and anticipate responses for when they encounter people of faith.

“The goal is to help people become more thoughtful and more reflective about their faith-based beliefs,” explains the app’s creator, Peter Boghossian, on the Atheos website. This gentler approach is something of a departure for Boghossian, a philosophy professor at Portland State University whose first book was titled A Manual for Creating Atheists. Boghossian has openly referred to his attempts to “disabuse” people of their faith as “interventions,” which include some less than charming rituals. For example, Boghossian said in an interview that he regularly went out of his way to be served by a bank teller who wears a cross, so that he could deploy his rational pedagogical tools on her.

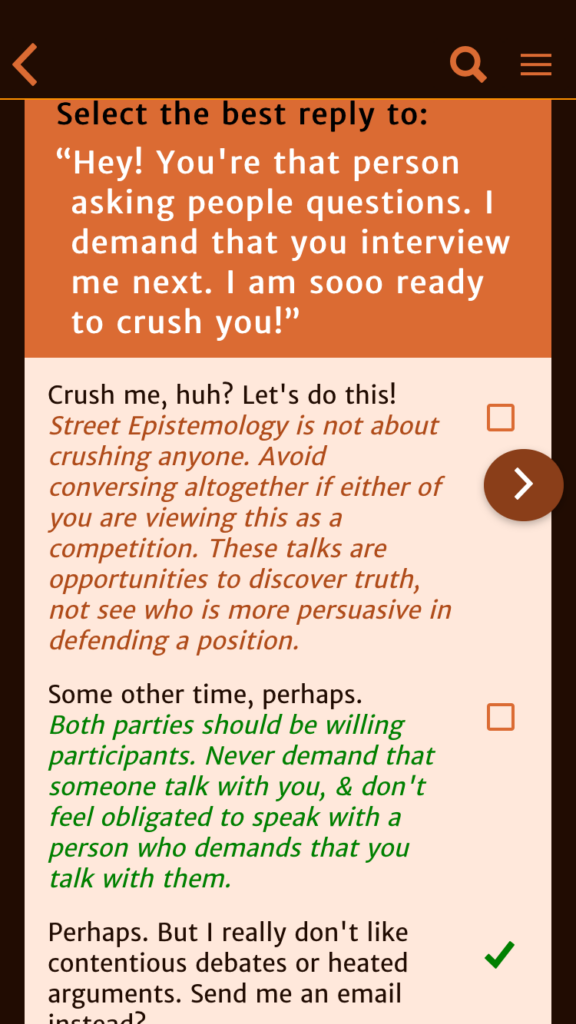

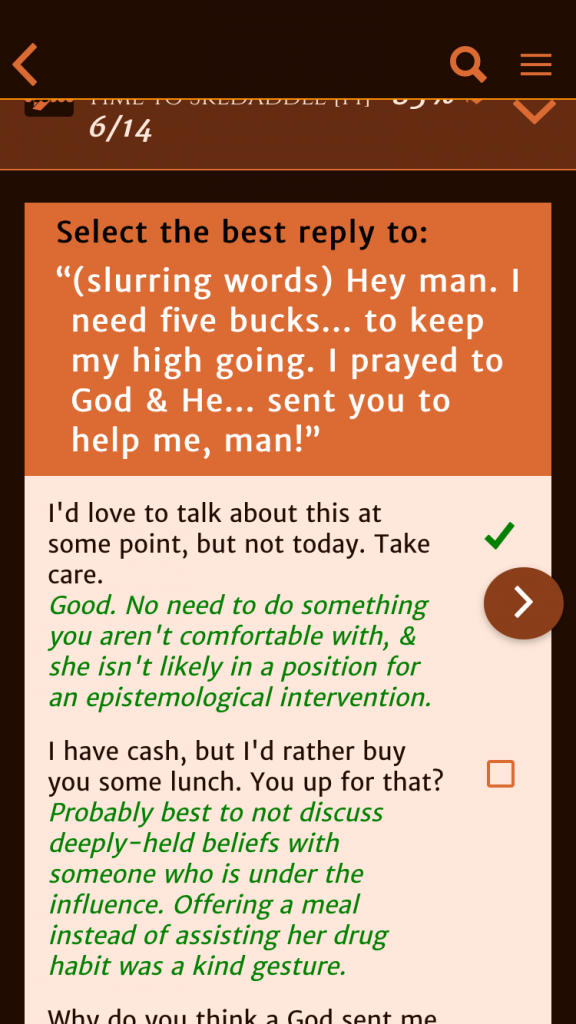

With Atheos, Boghossian and his collaborators seem to be aiming for a gentler tone. The correct answers in the app are usually assertive but tactful. They often come in the form of additional questions for the believer. If the person of faith in the scenario is aggressive, hostile, or otherwise potentially difficult to talk to, the Atheos app steers users away from engaging with them.

The emphases on inquiry, diplomacy, and de-escalation are all admirable, but as noted earlier the tone is not always free of condescension.

Writing realistic dialogue for hypothetical conversations is a very particular skill, and several of the scenarios reflect a deep disdain for believers. At times, the app casts believers as belligerent doofuses:

…or violent bullies:

Another scenario assumes that you might be tempted to lecture an intoxicated panhandler about epistemology and divine experience:

These particular interactions may seem contrived, but hostility is a common experience for many non-believers. Atheos is coming at a time when Americans continue to largely view atheists as “moral outsiders,” despite abundant research demonstrating that secular societies are the opposite of the hedonistic dens of crime and despair that some believers suggest a godless society would become.

Christine Vigeant and Sarah Paquette, both former students of Boghossian, are the managers of Atheos. “We aren’t interested in making atheists. We are interested in making people reason more effectively, to make their arguments based on reason,” Vigeant told me. She and Paquette explained that the scenarios were written by dozens of contributors who have had a diverse range of encounters with believers, including very aggressive interactions.

Because Atheos discourages engagement with hostile or clearly obstinate people, it can be difficult to discern for whom the app is intended. After, all what is the purpose of engaging with religious people who are non-violent, moderate, and not attempting to convert anyone themselves? “A lot of times people who are moderate give cover to violent beliefs because they are using the same kind of reasoning. Moderate religious beliefs transfer over into the public sphere,” argued Vigeant, using the example of restricted reproductive rights as such a spillover effect.

When asked about the belligerent reputation of many of modern atheism’s most outspoken leaders, both agreed that there was a tendency for controversial firebrands to receive the most attention, and for their followers to mimic that antagonism in their own discussions. Instead of setting themselves up in opposition to this brand of atheism, Paquette sees an opportunity for growth. “The more they have the opportunity to see good behavior modeled, we have a chance of having positive discourse and improving the way we communicate,” she said. Paquette noted that the Atheos app not only tells people the most appropriate response to the argument at hand, but also explains why the more aggressive or dismissive ones are wrong.

If user reviews are any indication, Atheos has been instructive to several non-believers who sought structure and resources for their conversations. Atheist blogger Courtney Heard wrote a glowing review on her site, Godless Mom, where she described what a great learning experience the app was. “It’s not just taking me through common conversations that I get frustrated with frequently, but it’s also proving, with each step further into the app, that you can deal with these conversations and questions diplomatically,” she wrote.

Not every reviewer approves of the diplomatic approach. User Val Hakan reviewed Atheos on Google Play with two stars, noting, “Just began with a few questions. So far it seems the right and wrong is based on compassion and politeness. Compassion I get, yes. Politeness though – sometimes it’s right to be impolite and honest.” The collective groan of people who are put off by New Atheism’s air of arrogance and self-righteousness is likely dwarfed by the collective groan of atheists who are tired of this rude and cavalier minority taking center stage.

Users like Hakan represent a highly visible attitude among atheist movements today. When non-believers insist that they are inheritors and owners of The Truth, many people, understandably, view them as dogmatists, comparable to the religious zealots they purport to detest. These people do not represent the vast majority of non-believers, but they are disproportionately visible, making it an uphill battle to replace them with more a conversation-oriented, empathetic image of atheism.

And because there is perhaps no atheist more visible (and vocal) than firebrand biologist and Islamophobe Richard Dawkins, it might be surprising some that this gentler approach to atheism was created in partnership with The Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science.

When I asked a couple acquaintances to try the app, both were put off by the association with Dawkins. “That this is produced by The Richard Dawkins Foundation and his name is prominent isn’t exactly inviting,” said Eric Gregory Snow, an Episcopalian serving as Chaplain and Technology Integrator at St. Thomas’s Day School in New Haven.

Safy-Hallan Farah, an editor in Minnesota, was raised Muslim and currently identifies as Muslim. But, she said, “I don’t necessarily subscribe to every tenet of the faith. I would say I’m all over the place and very much a passive believer.”

Farah said she was a huge Dawkins fan when she considered herself an atheist in her late teens, but she found the New Atheists increasingly myopic as she became more familiar with their work. “Dawkins and all the skeptics I used to admire don’t complicate their analyses,” says Farah. “They’re untrustworthy to me because their criticism of Islam is Orientalist and selective and often just a way to despicably condemn black and brown people with ‘reason and rationality.’”

Of course, Richard Dawkins himself wasn’t sitting around writing code and coming up with reasonably civil responses to hypothetical religious proclamations for Atheos (although some less famous but equally antagonistic thinkers like David Silverman did contribute to the app’s content). And for many atheists, even those not prone to Dawkins’ venomous outbursts against religious people, his name lends the app credibility. He remains a figure of liberation from faith to many. (I once counted myself among them and wrote this defense of Dawkins in 2014. I later learned about views that constitute blatant bigotry on his part, and I would not write any defense of Dawkins today.)

In our interview, Vigeant and Paquette both emphasized the distinction between the man and the foundation bearing his name, noting that his approach is useful for a different set of goals. “The firebrand approach can be helpful on a broader level, if you’re talking to a large audience or if you are a public figure,” says Vigeant. “But we are interested in the one-on-one conversations. At this level, we take a kind approach.”

I asked Snow to try Atheos because of his personal history with an evolving faith. Snow was raised as a conservative evangelical in Northern Virginia and was “intent on converting the world to my particular theological conclusions.” In college, because of his experiences in the classroom and in witness to “the catholicity of the Church,” he became an outspoken proponent of progressive values inside and outside the institutional church.

After exploring Atheos, Snow was skeptical of the app. “It doesn’t seem to question why people have faith—it assumes dogma and brainwashing, but doesn’t really say much for people who come to faith later in life after profoundly meaningful experiences,” he said. “Why are you trying to take this from them? Even if you’re doing it nicely? It seems to assume that people will enjoy being finally free of the oppression of anti-rational things.”

Farah expressed similar concerns when she tried the app. After explaining that her disconnect from the faith in which she was raised could feel alienating, Farah said, “I believe in God, though my belief often flounders. I don’t have that unshakable, uncritical, all-consuming faith so many people have. I honestly envy that. ”

“I want a strong faith so badly, more than anything,” she told me. Basically, Farah was unsure what Atheos had to say about people for whom faith is not a burden, but a blessing. How did Atheos deal with the fact that for many believers, the loss of God in their lives is a profound and painful experience?

In our conversation, both Paquette and Vigeant were sympathetic to that particular crisis. “A lot of people don’t consider the emotional ramifications of talking about their God belief. When you’re talking to people about God, you’re talking to them about more than God. You’re talking about their family, their social structure, who they go on Sunday cookouts with, and who has supported them their whole lives,” said Paquette. “So that’s definitely somewhere that we could grow,” she added without hesitation, noting that they could add essays to the resources or new scenarios that address sensitivity toward the experiences of believers and would-be believers.

The desire to make the app work better seems sincere from the interface itself: Atheos features an option for users to leave comments on each of the questions, suggesting alternatives and additions for future updates.

Vigeant and Paquette were courteous, but they never wandered into the realm of deference or compromise: the Atheos team is steadfast in its commitment to reason and science as superior lenses through which to see the world. They also care deeply about empowering non-believers who have long been burdened with explaining their lack of belief instead of the other way around. “We aren’t the ones who are making a knowledge claim. We would like to put the burden of proof back on the people making a claim,” said Vigeant.

But atheists would do well to consider their own truth claims about believers too. Quite simply, there is very little evidence that the removal of religion from a society leads to a more peaceful, just, and prosperous world. The idea that we would be happier if everybody subscribed to certain rationalist precepts can seem like its own kind of faith claim, or like a rejection of the principles of a pluralistic democracy that values a multiplicity of viewpoints.

You can rattle off competing theories about the virtues and dangers of belief and non-belief for days, but it would not be likely to convince someone on the opposing side to change their position. But the team at Atheos claims that they are not in the business of converting people so much as challenging people, including the non-believers who use the app.

The gamified Socratic dialogue and library of essays and resources on Atheos are a good starting point. Atheos would do well to add nuanced, more human elements to what are currently one-dimensional caricatures of faith. But perhaps the most challenging and significant element of the app is fundamental to its basic design: every situation or argument has more than one right answer.

* * *

Also on The Cubit: “I don’t believe in God, but I’m not on David Silverman’s team.”

The Cubit is RD’s portal on science and religion. To read more, follow us on Twitter @TheCubit or explore our archives.