Religion without God: “Cults,” Pious Atheists, and Our Own Human Bodies

Tired old Protestant-inflected definitions of “religion” are losing hold in diverse Western nations. And it’s about time.

Read More

Tired old Protestant-inflected definitions of “religion” are losing hold in diverse Western nations. And it’s about time.

Read More

In the beginning were the stars, the cosmos calmed, ordered, still. Like every other film announcing its mytho-logic from the get-go, the camera angle of Cloud Atlas’ first shot tilts from the milky heavens above, to life in the mortal-bound realm below.

Read More

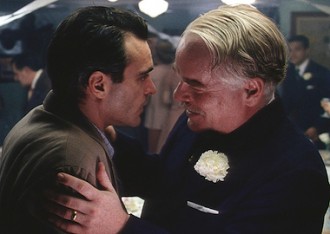

While Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master provides the latest (and greatest) vantage point, 2011 saw the release of three solid films on the topic. Why now?

Read More

The reclusive filmmaker understood that the truth of history, like myth, can only be approached as a sensual experience.

Read More

What might it mean for a synagogue, a church, a mosque, or a temple, to set up a video screen in its sanctuary and play these images of death from September 11—and then turn around and respond to them? What reinvented rituals might result from a ritualized, contextualized reception of these images? Such communal framing gets us beyond the questions of morbid voyeurism because it eliminates the one-way dimension and places images within a social setting. It further allows us to reflect and come to terms with dying, thereby stirring the potential for a good death.

Read More

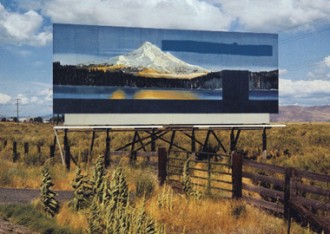

Kinkade challenged the high-brow haughtiness of the art world, grew rich in the process, and seemed to fumble around, rock-star like, with drinking and bad behavior. Liberals scoffed at the hypocrisy of yet another social-religious conservative who can’t live up to a decent set of moral standards, while his mass-produced images were hugely loved, especially by evangelical Christians who felt that here, finally, was an artist for them. He called himself the “Painter of Light” and then trademarked the phrase. He includes a Christian fish (icthus) above his signature—but he’s also alleged to have urinated on a Winnie the Pooh figure at Disneyland, among other socially unacceptable activities.

Read More

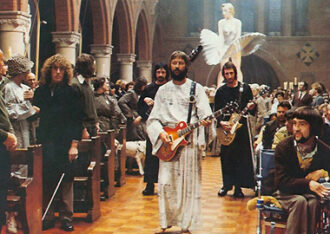

Russell is continually, even post-mortem, called “provocative,” “controversial,” and “iconoclastic.” And at least a few of these obits have noted his conversion to Roman Catholicism all those years ago, though he was never quite settled in his faith. Certainly there was religious content in his films—the nuns and priests in a sexual standoff in The Devils (1971), Anthony Perkins’ creepy street preacher in Crimes of Passion (1984)—but it was the human experience that Russell so strangely charted that leaves me thinking of his “religious” nature. He portrayed the depths of human depravity and desire, of lust and liking.

Read More

For Jeff Sharlet, the weird is out there: lost in the Wild West; hidden behind suburban fences and Hell Houses; on scratchy 1920s blues recordings and Mennonite funerals. His rare gift has been to make friends with the weird and almost make peace with it—which doesn’t mean he’s not skeptical.

Read More

The film is disingenuous—or rather the marketing for it is—as it suggests that we make a choice between nature and grace. One reviewer suggests that it’s about the middle way, about the redemption of siblings.

Read More

The top films for 2010—especially those up for this Sunday’s awards—leave most of the species-specific questions behind. Instead this year’s crop reflects anxieties (as well as promises) about who we are and who we might be becoming in and as humans, in our own skins—never mind the “prawns” or “Na’vi.” Questions provoked by this year’s films include those concerning the nature of our selves in connection and collision with our families, our larger social institutional entanglements, and our own bodies. The other key theme, effecting each of the others, had to do with the ways new media technology is inserting itself into our intimate lives, and changing our identities, both public and private.

Read More