As more details emerge about the grisly murder by stoning of a 70-year-old Philadelphia man by a 28-year-old who accused him of “homosexual advances,” it appears that this is a story as much about mental health and human vulnerability as it is about homophobia.

Murray Seidman, 70, had sustained a brain injury at birth that left him with the mental capacity of a seven-year-old. For the first twenty years of his life, he had been institutionalized. For the last forty, he had managed to live independently, working in the laundry department at Fitzgerald Mercy Hospital in Landowne, Pennsylvania. According to his brother, Murray Seidman “was very empathetic and very social with all people.”

In 2009, Seidman developed a friendship with 28-year-old John Joseph Thomas, a psychiatric patient at Fitzgerald Mercy.

In 2010, both Seidman (who was raised Jewish) and Thomas joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His brother reports that it was a “good thing” for Murray to join a welcoming and caring Mormon congregation.

In the summer of 2010, Thomas convinced Seidman (over protests from Seidman’s family) to give him power of attorney over his affairs.

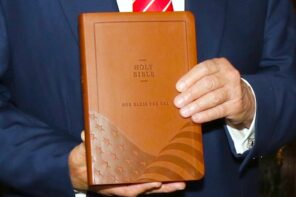

In January, Thomas beat Seidman to death with a sock full of rocks, then justified his actions by accusing Seidman (whom his brother characterized as “asexual”) of making homosexual advances and claiming that the Old Testament prescribed stoning for gay people.

The better we tell this story, the more complicated it gets. Yes, it is a story about how the Bible lends itself to predatory usage, especially the so-called “clobber verses” of Leviticus. For those of us who care about Mormonism, it’s also a story about Mormonism and the way our faith, with its active proselytizing agenda, welcomes just about anyone who shows a willingness to belong; and it’s a story that leaves many LDS people, sensitive to our faith’s record on LGBT equality, grappling with the question of whether Thomas drew any imaginary encouragement from his newfound Mormon context.

But mostly, really, it’s increasingly clear that this is a story about mental health, human predation, and human vulnerability. Religion is and has always been a primary place humans go to grapple with our vulnerability. But religion does not relieve us of our capacity to harm one another. In fact, sometimes, religion even creates opportunities for vulnerability and predation.

To what extent was John Joseph Thomas capable of gauging the consequences of his choices? Did his mental health problems and predatory instincts propel his attraction to religion and religious community in general and Mormonism in particular?

Spinning the story as yet another evidence of the murderous homophobia of religion—as some bloggers have tried to do—may be immediately satisfying, especially to LGBT people who have experienced belief-motivated homophobia and who live with the daily awareness of their own vulnerability to homophobic violence. But doing so impacts LGBT believers and scholars who’ve worked decades to put Levitical “clobber verses” in their proper context. (RD covers these issues here and here.)

Below the homophobic justifications of the accused murderer, it’s clear that mental health is an equally vital issue at work in this terrible story. Mental health is a spiritual and religious issue, one that encompasses a tremendous responsibility for an ancient human problem and affords few easy answers.