In a blog post that made waves in the Christian press last week, Billy Graham warns churches to “prepare for persecution.” Message aside, determining whether or not the nearly 97-year-old evangelist actually issued this warning himself is another matter.

A new book bearing the byline of Billy Graham presents scholars of contemporary religion with a similar puzzle. Did Graham actually write Where I Am: Heaven, Eternity, and Our Life Beyond, a book that, despite its title, focuses mostly on hell?

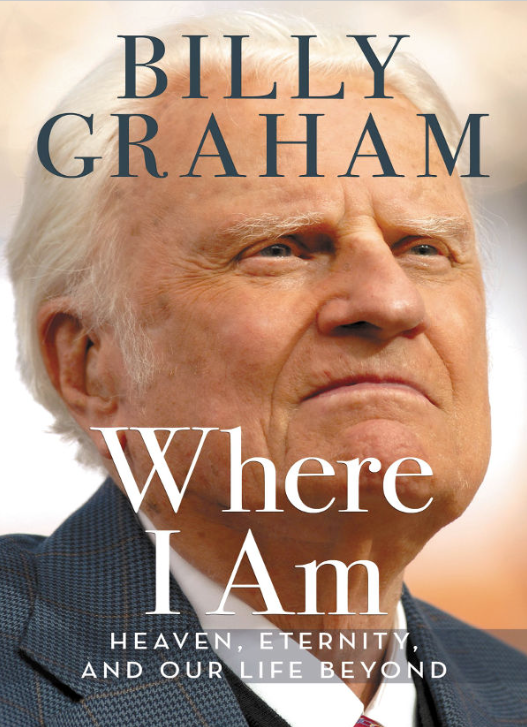

Where I Am: Heaven, Eternity, and Our Life Beyond

Billy Graham

Thomas Nelson

(October, 2015)

Pseudepigrapha—or documents falsely ascribed to illustrious authors—frequently crop up in the work of biblical scholars and other experts in antiquity. Researchers who regularly confront such mysteries ask first: what does the text say about its own authorship? And then: do any facts undermine this explanation of authorship, such as references to events about which the named author could not have known? Finally, does the text reflect the style and ideas of the ascribed author as found in his or her more solidly attributed works?

Posing these questions about Where I Am strongly suggests that the book is, in fact, pseudepigraphic—falsely named.

Billy Graham is the sole author listed for this book. His son Franklin’s name appears on a three-page foreword, and, perhaps more tellingly, Franklin is listed as the copyright holder. The foreword asserts that Billy began drafting Where I Am immediately after completing the 2013 book The Reason for My Hope: Salvation, intending that his outline for the latter book “would be fleshed out using his archival sermons.”

The foreword does not explain who would be responsible for this fleshing out.

A Graham byline is not definitive proof of authorship. Many, many texts that have appeared over the years with that byline were not written solely, or even primarily, by him. The “My Answer” syndicated newspaper column, for example, for years featured Graham’s name and picture, but it was written by Billy Graham Evangelistic Association staff. About once a year, the column acknowledged that Graham approved rather than wrote the answers, and even this statement didn’t mean that he had personally approved every word of every column. Graham was far too busy during his public ministry to write as often for publication as his bylines would indicate.

Working with other writers to produce a text is one thing; not working with them is something else. There are medical reasons to believe that Graham did not take an active role in the writing of Where I Am. Graham was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the early 1990s, a diagnosis that was later revised, according to some sources, to hydrocephalus. Both conditions cause memory loss. When Newsweek editor Jon Meacham spent time with Graham in 2006, the evangelist was unable to recite from memory Psalm 23, one of the most familiar passages in the Bible.

It’s odd, then, that Where I Am is organized as a walk through the Scriptures from Genesis to Revelation, with scores of other biblical texts incorporated into the chapters. There are more, and obscurer, Bible passages cited in this book than in the sermons that allegedly supplied its substance. Graham lamented to Meacham that he didn’t know as many biblical texts as some of his friends. The reader of Where I Am is asked to believe that Graham has a better command of the Bible now than he did 10 years ago.

Graham also suffers from diminished eyesight. His longtime public relations manager A. Larry Ross wrote in 2013 that, several years earlier, Graham had printed a Bible verse in bolded, 72-point type in order to be able to read it. Yet the introduction (not Franklin’s foreword) to Where I Am makes multiple references to bloggers getting the theology of heaven and hell wrong. A man who can barely make out a banner headline almost certainly does not follow blogs.

Claims of Graham’s authorship of Where I Am are already shaky, then, before one even considers the book’s content. Graham biographer (and, full disclosure, this author’s graduate advisor) Grant Wacker deems the book’s emphasis on hell entirely out of step with Graham’s mature theology. “Over the course of Graham’s career, he talked less and less about hell until the end (of his career), when he barely mentioned it,” Wacker told the Charlotte Observer. Indeed, a Google search on “Billy Graham” and “hell” yields few results that are not related to the recent book. Several articles that do turn up criticize the evangelist for soft-pedaling the idea. For example, The Baptist Pillar (“Canada’s Only TRUE Baptist Paper”) once stated that “Billy Graham has declared his allegiance with the blasphemous apostasy of our day” by preaching that hell might be more metaphorical than actual.

The 1983 sermon that roused the Baptist Pillar’s ire provides an interesting comparison between spoken words that were indisputably Graham’s, published words that were basically Graham’s, and words that appear in Where I Am. The published title of the sermon was, “There Is a Real Hell.”

Thanks to Liberty University’s archives, anyone can watch Graham preach this sermon to a large crowd in Sacramento, California. In it, Graham described hell as an “unpopular, controversial, and misunderstood subject.” He continued, “I’ve heard some preachers preach on hell as though they were glad there was a hell and glad that people were going there. But I’m not. I don’t like to preach on it. I do it only because I’m commanded in Scripture to preach the word. And it’s against the backdrop of God’s love, mercy, and grace that I must preach it.” Regarding that backdrop, Graham stated, “You can never understand hell, though, until first you understand the great love, mercy, and grace of God, and it should never be preached by any preacher without tears.” (Graham did not tear up at any point on the video, though he described himself as speaking with a “broken heart.”)

Hell was not, Graham asserted, created for human beings, but for the devil and his angels. Humans find themselves in hell when they reject God—and hell begins in this life, not in the next. According to Graham, “The Bible teaches that there are at least three kinds of hell.” The first, “hell in the heart,” is humanity’s sinful nature, present in children at birth and manifested as soon as they start making their own bad choices. Acting on this sinful nature can produce a related “hell of guilt,” such as that experienced by a unnamed man whom Graham described as cheating on his wife. Impulses bubbling up from sinful nature can also produce a “hell of unrest,” the sort of fruitless seeking for inner peace that, in Graham’s view, drove the Beatles to India.

Secondly, according to Graham, there’s “hell around us.” It appears as lust, greed, and hatred. It spawns wars and riots. Graham repeatedly linked his thoughts on hell with his concerns about the state of the world, at times paying more attention to the latter than the former. He preached, “A lady said sometime ago, ‘I hate the very thought of hell.’ So do I! And I also hate the sin that sends them there. I hate war. I hate the fact that people are starving in the world.” Unfortunately, Graham admitted, hating these things did not make them go away.

Even the third kind of hell, “hell in the future,” was connected in Graham’s sermon to present-day concerns. “The future hell is a projection of the hell that you have now in your heart, in your home, in our world, except it goes on and on,” he said. Perhaps there would be fire, smoke, and stench. Graham observed that Gary, Indiana, looked a bit like hell if you peered down from an airplane. But perhaps hellfire was metaphorical. Graham mused, “[Jesus] uses the word fire, and I have often wondered if that is a terrible fire within our hearts for God, for fellowship with God, that can never be quenched. We’ve rejected God. We’ve turned our back on God. We can never know God. … [Hell is] the banishment from the presence of all that is joyous and good and righteous and happy.”

The printed version of this sermon appeared in the July-August 1984 issue of the BGEA magazine Decision. The article, with Graham’s byline, began with the preacher’s reluctance to address the topic, stated that hell was created for the devil and his angels, described the three kinds of hell, and speculated that the fire of hell was a burning in the heart for fellowship with God. Many of the words of the article were exactly those Graham had preached. The article was, however, much shorter. It did not include the stories about the cheating husband, the Beatles, or flying over Gary, Indiana. It also skipped most references to the world’s problems and any reference to “tears” or a “broken heart.”

In all, the article was a bit sterner than the sermon, more biblical, less conversational, but not theologically distinct. Without deep archival research, there is no way to know whether Graham whittled down the sermon text himself or whether the edits were performed by someone else.

Some words from Sacramento show up again in the opening pages of Where I Am, but then the text takes a very different turn:

The doom of Hell was not intended for human beings. God created us for fellowship with Him, though many have turned their backs on Him. Hell was created for the devil and his demons, and Satan wants to take the world with him into this diabolical place.

Don’t think for one minute that Hell will be the “hottest” happy hour of all. Those who find themselves there will remember the hour of decision that determined their fate; they will face the inferno of God’s wrath that will last not for an hour but for all the never-ending hours of forever.

Graham alluded to God’s wrath back in 1983, but he foregrounded God’s “great love, mercy, and grace.” The relative importance of the two concepts is reversed in the new book.

Of course it is possible that Graham changed his mind. All available evidence outside the new book and accompanying statements by Franklin Graham suggests, though, that Graham grew less certain about damnation in the years after 1983.

A YouTube video critical of Graham includes footage of a 1997 conversation between the evangelist and Robert Schuller, in which Graham raises the possibility that people who do not even know Christ might yet be saved. Similarly, he told Meacham in 2006 that it would be “foolish” for him to speculate whether only Christians could get to heaven. “I believe the love of God is absolute,” Graham said then. “He said he gave his son for the whole world, and I think he loves everybody regardless of what label they have.”

The most charitable view of pseudepigrapha is that it reflects a desire to read a few more words from an honored writer whose pen has fallen silent. Less charitably, such texts reflect someone’s desire to hijack an author’s reputation for ideological purposes or financial gain. Whatever is going on with Where I Am, Billy Graham has little, if anything, to do with it.