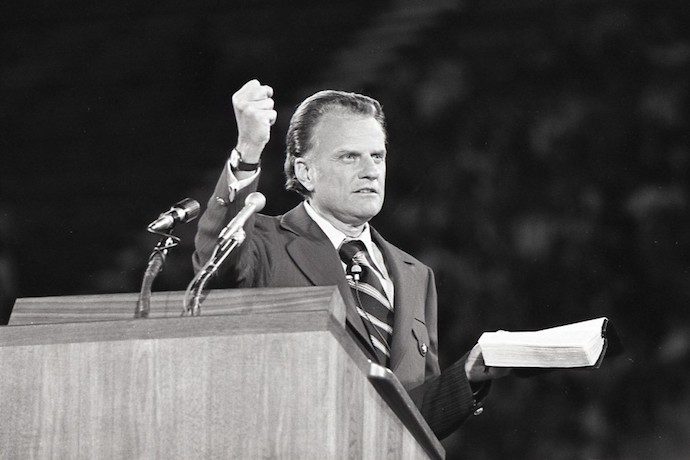

Billy Graham, by any measure the most famous religious figure of the twentieth century, died today at his home in Montreat, North Carolina. He was ninety-nine years old.

In a career that extended well over half a century, Graham took a simple evangelical message—give your heart to Jesus, and you will be “born again”—to millions around the world. The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, the organization he founded to facilitate his ministry, boasted that Graham preached to more people than anyone else in history, a claim that probably cannot be verified but is almost certainly true.

Early Life

Born November 7, 1918, near Charlotte, North Carolina, William Franklin Graham Jr. worked on his father’s dairy farm. In the fall of 1934, when he was a teenager, Billy Frank, as he was known, accompanied several of his friends to a revival meeting conducted by an itinerant evangelist, Mordecai Ham. The revival had already stirred the passions of many in Charlotte, in large part because of Ham’s public speculations about the sexual behavior of students at Central High School and because of his denunciations of the local clergy, many of whom had opposed his revival campaign.

Graham recalled later that he had gone to scoff at the preacher, but he was captivated instead. After several meetings, Graham accepted Ham’s invitation to come to Jesus, as the choir sang “Just as I am, without one plea.” Although he worried later that his conversion may not have taken hold because he did not evince the emotions that he saw in others, Graham’s conversion would shape the direction of his life and would reshape the course of American evangelicalism in the twentieth century.

Prior to enrolling at Bob Jones College, Graham worked the summer of 1936 as a highly successful door-to-door salesman for the Fuller Brush Company. He spent only the fall semester at the famously fundamentalist school, then located in Cleveland, Tennessee, before transferring to Florida Bible Institute. Jones, the school’s founder and president, had tried to bully Graham into staying at Bob Jones College, warning that “if you leave and throw your life away at a little country Bible school, the chances are you’ll never be heard of. At best all you could amount to would be a poor country Baptist preacher somewhere out in the sticks.”

Graham’s decision to leave Tennessee for Tampa may have been motivated less by theological scruples than by the allure of sunshine, but that transition symbolized a larger movement from the starchy fundamentalism of his childhood, characterized by comprehensive behavioral standards and strict separation from theological liberalism and the perils of “worldliness,” toward a more inclusive evangelicalism. Florida Bible Institute was hardly a bastion of liberalism, evangelical or otherwise, but Graham, though he remained theologically conservative throughout his life, ultimately rejected the dour, narrow fundamentalism of Jones in favor of a less-militant evangelicalism, which sought to speak the idiom of the culture in order to communicate the gospel.

While a student in Florida, Graham felt a divine call to preach and began doing so on street corners and, later, as a supply preacher. Several months before completing his studies at Florida Bible Institute, Graham was ordained a Southern Baptist minister. Feeling he needed still more education, however, he enrolled at Wheaton College in the western suburbs of Chicago. There he met, and eventually married, Ruth McCue Bell, daughter of missionaries to China, who had initially resisted the advances of the young preacher because he did not aspire to be a missionary. By the time he graduated from Wheaton College in 1943, Graham had developed the simple, earnest preaching style for which he would become famous.

Early Career as an Evangelist

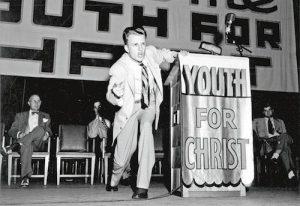

Graham briefly became pastor of small congregation in Western Springs, Illinois, and, at the invitation of Torrey Johnson, hosted a weekly radio program, Songs in the Night. Shortly thereafter, Johnson recruited Graham to preach at Saturday-night rallies in Chicago’s Orchestra Hall, part of the outreach for a new organization called Youth for Christ. In 1946, Graham joined the staff of Youth for Christ, where he met and befriended Charles Templeton, another itinerant evangelist for Youth for Christ.

Templeton and Graham became known as the Gold-Dust Twins, and many contemporaries regarded Graham as the lesser preacher. Templeton’s intellectual restlessness prompted him to apply for admission to Princeton Theological Seminary, where he was admitted despite the fact that he had never graduated from college. Then, meeting Graham at the Taft Hotel in New York City, Templeton challenged his friend to attend seminary with him in order to deepen his theological understanding.

Graham pondered the possibility at length, troubled by Templeton’s intimations that elements of the Christian faith were not intellectually defensible. For Graham, a turning point in his life—and in the entire revival enterprise of the twentieth century—occurred shortly thereafter while he was staying at the Forest Home Conference Center in Southern California. While hiking and praying there in the San Bernardino Mountains, Graham decided to set aside Templeton’s challenge, to banish his own intellectual doubts, and simply to “preach the gospel.”

He did just that, descending the mountain to conduct his famous Los Angeles revival campaign of 1949. Abetted by prodigious advance work, which would become the hallmark of Graham’s evangelistic efforts, Graham, billed as “America’s Sensational Young Evangelist,” conducted services beneath a circus tent, dubbed the “Canvas Cathedral,” at the corner of Washington and Hill Streets. Graham’s enormously successful Los Angeles crusade in 1949 brought him national attention, in no small measure because newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, impressed with the young evangelist’s preaching and his anti-communist rhetoric, instructed his papers to “puff Graham.” From Los Angeles, Graham took his evangelistic crusades around the country and the world, thereby providing him with international renown.

Organization

In 1948, following a successful revival campaign in Augusta, Georgia, and a cross-country drive to California, Graham and his associates (whom he always called his “team”) had met at a motel in Modesto, California. Worried about Sinclair Lewis’s Elmer Gantry caricature of itinerant preachers, Graham asked his associates to consider the pitfalls that had discredited earlier revivalists and to propose ways to avoid those perils.

After prayer and discussion, they decided on several principles: their salaries would be fixed by the organization, not a portion of the offerings; they would never criticize any religious leader; they would never provide estimates of crowd sizes, lest they be accused of exaggeration; they would take extraordinary precautions to avoid sexual impropriety, or even the appearance of such. Cliff Barrows, Graham’s choirmaster and one of the team members present, referred to this set of principles as the Modesto Manifesto, although he insisted there was nothing official about that designation. Graham maintained that he and the team had been abiding by those principles all along, but the codification of the Modesto Manifesto helped to insulate Graham and his associates from any serious accusation of wrongdoing.

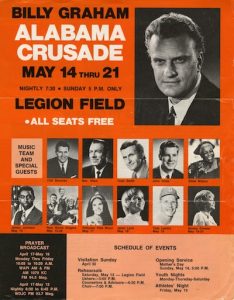

During the course of his Portland, Oregon, crusade in 1950, Graham made several decisions that would affect the course of his career and shape the revival enterprise. First, at the urging of several supporters from the world of business, he decided to incorporate his revival apparatus as the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, thereby adopting a business model of organization and efficiency. After initial resistance, he also agreed to undertake a radio broadcast, the Hour of Decision, thereby tapping into the newly expanding universe of electronic media. Later, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association would televise his crusades and would also produce motion pictures under the aegis of World Wide Pictures, a division of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

During the course of his Portland, Oregon, crusade in 1950, Graham made several decisions that would affect the course of his career and shape the revival enterprise. First, at the urging of several supporters from the world of business, he decided to incorporate his revival apparatus as the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association, thereby adopting a business model of organization and efficiency. After initial resistance, he also agreed to undertake a radio broadcast, the Hour of Decision, thereby tapping into the newly expanding universe of electronic media. Later, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association would televise his crusades and would also produce motion pictures under the aegis of World Wide Pictures, a division of the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association.

Above all, however, the Association brought corporate efficiency to the world of revivalism. The organization groomed and then jealously guarded Graham’s public image, orchestrated the details surrounding his evangelistic efforts, and provided advance work that would be the envy of any presidential candidate. Once a site had been chosen for one of Graham’s crusades, for instance, the planning would take three years, and several staff members would actually relocate to the city in order to coordinate the preparations in concert with local churches. In addition to Graham, the Association also sponsored a number of “associate evangelists,” including Howard Jones, Ralph Bell and Leighton Ford. The Association published Decision magazine, and Graham’s syndicated column, “My Answer,” appeared in newspapers across the nation.

Politics

By his own account, Graham enjoyed close relationships with American presidents, from Dwight Eisenhower to Barack Obama (even though Graham met with Harry Truman in the Oval Office, the president was little impressed with the young evangelist). Although he purported to be apolitical, Graham’s most notorious political entanglement was with Richard Nixon, whom he befriended shortly after Nixon’s election to the United States Senate in 1950.

During the 1960 presidential campaign, Graham met in Montreux, Switzerland, with Norman Vincent Peale and other Protestant leaders to devise a way to derail the campaign of John F. Kennedy, the Democratic nominee, thereby assisting Nixon’s electoral chances; eight days earlier, Graham had sent a letter to Kennedy promising not to raise the “religious issue” in the fall campaign. Although Graham later mended relations with Kennedy, Nixon remained his favorite, with Graham all but endorsing Nixon’s re-election effort in 1972 against George McGovern, the Democratic nominee.

As the Nixon presidency unraveled amid charges of criminal misconduct, Graham reviewed transcripts of the hitherto secret Watergate-era tape recordings. Although the tapes provided irrefutable evidence of Nixon’s various attempts to subvert the Constitution, Graham professed to be physically sickened by his friend’s use of foul language. As late as 1992, Graham described Nixon as one of the “great men” he had known.

Aside from his strident anti-Communism in the 1940s and 1950s, Graham’s own political leanings were never well defined—or at least they were never publicly articulated. He generally shied away from religiously inspired programs of social reform, insisting that the only way to change society is to “change men’s hearts.” That statement comported with his premillennialism, the belief that Jesus will return at any time—before the millennium, one thousand years of righteousness, predicted in Revelation 20—and that projects of social reform were essentially pointless. The only hope for meaningful change, according to Graham, lay in the aggregate effect of individual conversions rather than in programmatic reforms.

Graham occasionally took positions on other matters. During the military buildup of the 1980s, the erstwhile cold warrior came out against nuclear proliferation. In 2004, amid various efforts on the part of the Religious Right to post the Ten Commandments in public places, Graham, nominally a Southern Baptist, told Newsweek that he supported such efforts, despite the fact that they violated Baptist principles of liberty of conscience and the separation of church and state.

Fundamentalist Critics

In 1996, Graham and his wife, Ruth, received the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor that Congress can bestow a citizen. Although he consistently enjoyed approbation from the public, and he regularly appeared on lists of “most admired people,” Graham nevertheless endured criticism from the right, from fundamentalists who resented his move toward a more inclusive, irenic evangelicalism. Graham had already earned the enmity of Bob Jones when he left Bob Jones College for Florida Bible Institute after only one semester, but the real breech between Graham and the fundamentalists came in 1957 during his storied Madison Square Garden crusade in New York City.

Graham had been preaching in Paris in 1955 when word came that the Protestant Council of New York wanted him to conduct a revival campaign in Manhattan. “No other city in America—perhaps in the world,” Graham recalled in his autobiography, “presented as great a challenge to evangelism.” Sponsors of the crusade secured an option on Madison Square Garden for the summer of 1957, and the revival turned out to be a success, running for sixteen weeks and punctuated with massive rallies in Times Square and Yankee Stadium. Fundamentalists like Jones, Carl McIntire and Jack Wyrtzen were incensed, however, that Graham cooperated with the Protestant Council, whose ranks included theological liberals. They castigated Graham for compromising the faith and renounced him thereafter as a liberal and a turncoat. As late as 1992, for instance, when the executive producer for a PBS documentary on Graham approached McIntire and Bob Jones Jr. for interviews, both refused to comment.

By the twenty-first century, Graham, well into his nineties, had outlived most of his critics and endured as a kind of iconic figure in American revivalism. His evangelistic crusades around the world, his television appearances and radio broadcasts, his friendships with presidents and world leaders and his unofficial role as spokesman for America’s evangelicals had made him the most recognized religious figure of the twentieth century.