I heard Rev. Daniel Berrigan speak about eleven years ago on a snowy Saturday afternoon in Brooklyn’s beautiful St. Francis Xavier Church. He talked about reading the Bible as part of a spiritual practice. It occurred to me, then, that Berrigan liked the idea of Catholics reading and interpreting the Bible for some of the same reasons church teachers had so often tried to reserve that right for themselves.

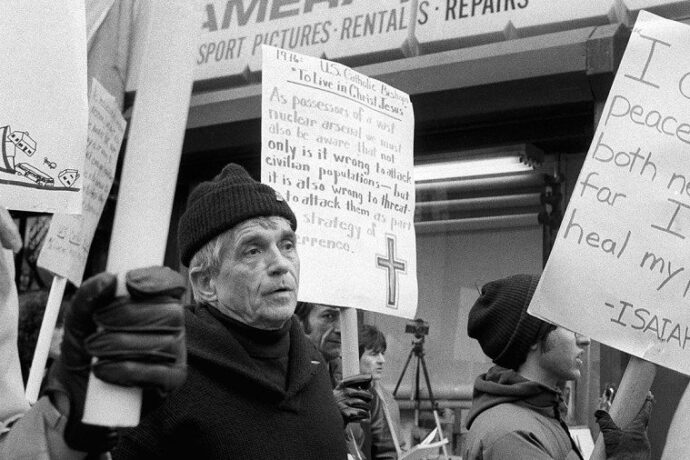

Being in Berrigan’s presence was a thrill—I had long followed his careers (I write lacking a better word for it) as activist, poet and priest. Even before I became a practicing Catholic around fifteen years ago, I drew spiritual encouragement from this activist teacher who put his body where his mouth was. Berrigan embodied the idea(l) of the “the word made flesh,” or in theology-speak: “living incarnationally.”

The first veil-free nun I knew was my seventh-grade English teacher in a parochial school in Yonkers. She was young, smart, confident, opinionated and taught all the things she was supposed to teach. I learned what a predicate nominative was that year, and that year I also began to read newspaper pieces, for school, about the Vietnam War. It was 1971. I got an “A” on a literature project in which I used Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War” as a poem. In one lesson, while introducing the concept of “pacifism,” Sister dropped the name of a priest called “Berrigan.” She recounted a story she’d heard from one of the Fathers Berrigan. I wish I remembered it all more exactly. It might have been Daniel:

“What does a pacifist do if someone comes at him with a knife?” a student had asked (the) Berrigan.

Answer: “Nothing.”

Then, “What if he comes at your mother with a knife?”

Answer: “I would place my body between my mother and the attacker.”

When the bell rang we filed out of the room talking about the story. We were 12. Half of us were boys. Pacifism? That was crazy. We didn’t get it. “Well, the guy with the knife would wind up stabbing you and your mother!” someone stepping forward to state the obvious exclaimed. That this story was expressed with knives, and not guns, says something about how far we have failed to come.

The edgy nun came for a school year and was soon gone. Shortly after she left, there was a new principal and a new pastor. The parish kept the folk mass, but by the end of eighth grade—1972—posters of fetuses began to appear on the street outside the church as the 9:00 mass let out, and the new pastor, an old Irish-American guy, was harping on communism and the menace of “Red China” on a weekly basis. I stopped going to mass regularly in the spring of 1972.

About thirty years later, personal crisis and desperation led me to search for a church. I had expected, at the beginning of this search, to land in a progressive Episcopal congregation, but surprised myself by winding up, in the year 2000, in a Roman Catholic parish. Why Roman Catholic? There were many reasons. At the top of the list: they had players like Daniel Berrigan. They were the word-made-flesh team.

Between 1995 and 1998 I had three children. By the time the youngest was a year old, I was schlepping all three to Sunday mass. On September 11, 2001, the day the towers fell, I went to pray in my church while two miles away my priests were blessing buckets of body parts. On a blisteringly sunny April morning in 2004, after being up all night, I knocked on my pastor’s door asking him to officiate at the funeral of my suddenly-gone 45-year-old Irish twin.

I was already in deep, involved in a parish life, active in ministry, when I got a chance to say “hi” and “thanks” to Daniel Berrigan that day in Brooklyn in 2005.

Still, at that point, as it is now, being Catholic was hard for me. I was a leftist. I was a feminist. I thirsted for justice. I loved the church and my parish, but the patriarchy and its misogyny disgusted me ten years ago (and disgusts me, still, today). I was Catholic under protest. Educating myself about my religion helped—I read books about Catholicism, a little theology, encyclicals, a few biographies of saints and Church doctors. I developed a bizarre fascination with the Canon Code. But mostly, writing helped me stick with being Catholic. Reading poetry by Catholics and Catholic poetry—the poems of Daniel Berrigan were both—helped the most.

That Berrigan was a poet, that he worked as a poet, made all the difference.

As I read tribute after tribute to Daniel Berrigan during the weekend following his death, I remembered that presentation he gave on that snowy day at St. Francis Xavier. As both daylight and the talk began to wind down, Berrigan took questions. A man seated in the pew directly ahead of me—a gay man in attendance with his partner, it seemed—asked whether Berrigan’s work with people dying of AIDS had moved him to depart from/challenge the magisterium’s teaching on the use of condoms.

Berrigan took a long time to answer. I wanted him to jump in with a response I could adore. I watched him think. He surveyed the exquisite church, seemed to stop to admire the rose window backlit by fast-dimming snowlight. He scanned the Stations of the Cross. He paused, delayed. A tight suspenseful silence ensued. I thought I saw some anguishing in his deliberation. Maybe he wanted to say one thing, but, feeling constrained, had to say another. Maybe I read too much into it.

“Just because you can’t do everything,” he said, “doesn’t mean you have to do nothing.” One-part koan, one-part Jesuit equivocation?

Berrigan was a poet. You had to parse it slant.

“The church is our mother, but she is a whore.” Whether this famous line comes from a sermon of St. Augustine’s or from the pen of Dorothy Day, I have it via good Jesuit authority that Berrigan did actually say it at least once. Either way, the statement packs so much truth. The church is a mother, and she is a whore, and we Catholics love her. It’s easy to forget, among the several well-deserved secular tributes how very much Berrigan loved/loves the Church.

“The church is our mother, but she is a whore.” Whether this famous line comes from a sermon of St. Augustine’s or from the pen of Dorothy Day, I have it via good Jesuit authority that Berrigan did actually say it at least once. Either way, the statement packs so much truth. The church is a mother, and she is a whore, and we Catholics love her. It’s easy to forget, among the several well-deserved secular tributes how very much Berrigan loved/loves the Church.

If Father Daniel Berrigan can love her, I guess, so can I.

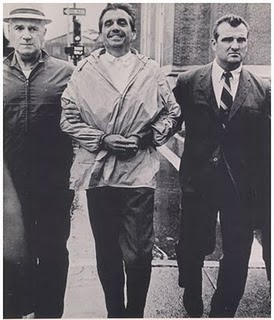

One Buddhist view of death would characterize Berrigan’s dying, like all deaths, as the shedding of a worn-out jacket. The soul freed of its tattered covering moves on to another life. That is somewhat but not entirely consistent with the Catholic teaching on death. As I mourn the death of this extraordinary man, whom I see in the famous photo smiling and more free than most, maybe, in handcuffs, smiling. I think of the Christ and the body. I think of how expert and deliberate Berrigan was in using his body to hold on to the Christ of his imagination. I think of how in his work he married word and flesh. I think of the poet Berrigan and his big body of work. I think, he’s not all the way gone.