This past weekend the New York Times ran a column—”Setting Aside a Scholarly Get-Together, For the Planet’s Sake“—about the American Academy of Religion’s new commitment to battling climate change.

In Oppenheimer’s piece we learn that the president of the AAR, Laurie Zoloth, believes we should take a “sabbatical” from our annual national meetings by simply deciding not to meet every seventh year.

The purpose of such a break from the rhythms of conventional academic life would be to lighten the carbon load on the planet, since these annual national meetings, attended by well in excess of 9,000 attendees, require significant national and international air travel, nearly a week’s stay in hotels—not known for their commitment to a “green” environmental ethic—as well as increasingly cavernous convention centers, similarly unknown for their dedication to energy conservation, locavore provisioning or sustainability.

More than that, we learn that Zoloth was responsible for pressing program chairs at this year’s annual meeting to focus their sessions on “environment, ecology or related issues.” Nearly a third of this year’s meetings sessions dealt with precisely those topics. A success for President Zoloth.

While I have been a life-long environmentalist, and a believer in the real dangers of man-made climate change, Professor Zoloth’s proposal, and moreover, the ethos from which it emerges, tells us everything we need to know about the malaise poisoning the study of religion in the university.

In place of open-ended questioning, unbridled curiosity and pursuit of understanding, Zoloth’s leadership would have us set about to solve one of the gravest problems facing humanity. What could be wrong with that?

I believe that most of this effort is misguided, however well-intended. But I’ll start with what’s right about it, even if it might be for the wrong reasons: The Times article lauded Robert P. Jones’ study of the correlation between religious affiliation and attitudes to climate change. (White Protestant men – the GOP base? – were most skeptical of human influence upon climate change, for instance.)

Now, while such information does advance understanding, such studies are almost never done under the auspices of the AAR, an organization made up of theologians and humanists. The Society of the Scientific Study of Religion (SSSR), meanwhile, is populated mostly by empirical psychologists, political scientists, mainline sociologists, social psychologists and historians. The AAR, and the intellectual ethos it encourages, can hardly claim credit for the kind of useful information provided by Jones’ polling, since it eschews precisely the empirical methods and scientific ethos typical of the SSSR.

The real problem is that Zoloth has been drawn in by the challenge of her scientist colleagues at Northwestern, who apparently asked what the study of religion was doing about climate change.

Naturally, anyone would want to defend their discipline from the charge of being insensitive to a massive global problem. But, think again. Aside from volunteering religious studies students for enrollment in basic science courses, or organizing campus progressive political clubs to work harder to elect “green” candidates to public office, perhaps asking a religious studies professor to do something about climate change is absurd, or at the very least, peripheral.

Does such a challenge pass a preliminary test of likely utility? Must every discipline have some significant contribution to make to every social problem we face?

Maybe, as an academic discipline we ought to be show a little more humility. As much as we find it irresistible to pontificate, maybe there are times when a particular academic discipline needs to get out of the way and let those better placed get on with the work.

Am I being too harsh? Am I, in fact, countering my own proposal that we need “open-ended questioning, unbridled curiosity and pursuit of understanding”? Why shut the door on seeing how the study of religion can contribute to defeating climate change?

Well, two reasons come immediately to mind. First, as long as the study of religion is seen as a humanity or theology, and not social science, the kind of significant results obtained by social scientists will not be forthcoming.

Second, if we are to judge by reports of AAR papers and sessions responding to the challenge of Zoloth’s Northwestern science colleagues, the results cannot be encouraging. Oppenheimer lists, for example: “Strategic Essentialism as a Tactical Approach to an Eco-Feminist Ideology”; “The Staying Power Of Zen Buddhist Oxherding Pictures”; and “The Path Has a Mind of Its Own: Echo-Agri Pilgrimage to the Corn Maze Performance–An Exercise of Cross Species Sociality.” Worthy papers, in their respective areas, but not likely to halt the shrinking of polar ice caps.

+++

I find it hard not to conclude, after all this, that the study of religion, as reflected in the policies of the AAR, has simply lost its way. If the AAR thinks the main way the study of religion should move forward is for it to hitch itself to the latest star in the universe of social causes, it has ceased being an academic discipline: it has ceased conceiving research projects and teaching courses that have an integrity of their own.

What are the main questions that the study of religion should address? Are there problems of religion in the same sense as there are sociological (not “social”) problems, as Peter Berger has shown, or perennial problems of philosophy, as Bertrand Russell insisted? I have argued elsewhere that there are.

Finally, as a political progressive of many years standing, I too care about issues like climate change. But, I wonder why we progressives lack the kind of social activist leadership to mount such campaigns.

Yes, there are many who labor in these vineyards, and who do so nobly. Think only of our public health workers fighting Ebola in West Africa. Real heroes. But, where are the great figures who can articulate a compelling vision around, say, climate change? Al Gore tried, but then disappeared, deciding to get rich as a media wheeler-dealer. Have other social activist leaders lost their focus too?

I worry about this because of the ease today of blurring the distinction between social activism and other occupations—in this case, the university. As long as one feels one can do social activism with the security of tenure from the classroom, then one never fully commits to one or the other. Hence, we get academics who are part-time activists, and activists who are full or part-time academics: our academic life grows corrupt as the leadership of our social movements grows distracted.

Martin Luther King, Jr. did not make that mistake. Even though his PhD from Boston University would have placed him in the academic stream, he decided to devote himself completely to the liberation struggle. Our nation is immeasurably better for King’s ability to see these distinctions so clearly: one wishes our own leaders in the AAR could share this vision.

[Note: this post has been updated with a link to Professor Strenski’s article in Method & Theory in the Study of Religion: “Why It is Better to Know Some of the Questions than All of the Answers.”]

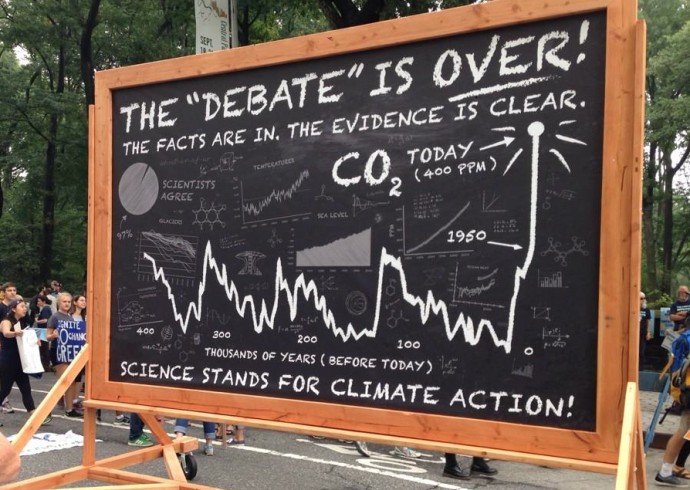

Photo by @PdeMenocal