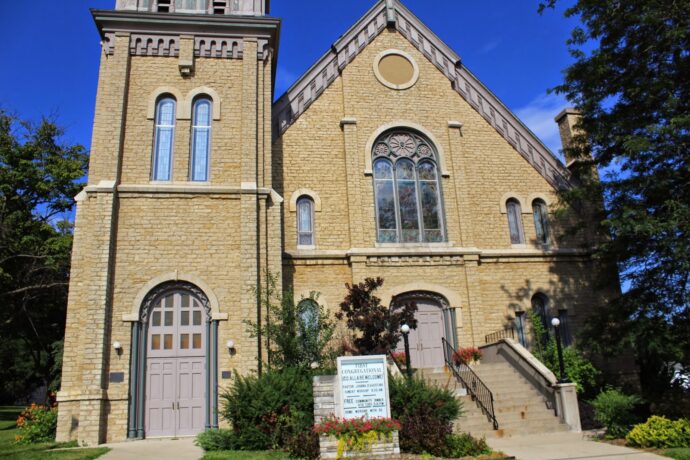

This Saturday, I’m off to a day-long meeting at a church with an interesting history. The town it sits in was originally formed as a utopian community, and some time later, the church was created in the image of those values. As the congregation’s website says,

We are proud that this church believed its calling was to follow the example of Jesus Christ, and in doing so to be controversial and even radical.

It certainly was. A few years later, a meeting was announced at a church worship service. Members of the congregation helped to organize a new and uncompromising political party with a candidate whose very nomination provoked an unprecedented national crisis.

As you’ve probably sussed out by now, that candidate was Abraham Lincoln, whose Republican party was founded in Ripon, Wisconsin1 on the basis of radical opposition to slavery. The original Grand Old Party was—believe it or not—the Religious Left of their day, built on the backbone of Methodists, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists (such as the church I’m going to visit), who sent their culture west from New England to make sure no more slave states entered the union.

I bring this up to put into proper context a lecture from Auburn University’s Paul Brandeis Raushenbush, descendent of the leading light of the Social Gospel movment Walter Rauschenbusch2 and now himself a leader of the Religious Left. Raushenbush, as it happens, grew up in Madison, and came back to the university to talk about the connections between what’s known as the Wisconsin Idea and religious progressivism:

John Bascom was born in 1827. He attended Williams College went to Auburn Seminary – where I now serve – and ultimately graduated from Andover Newton Seminary. He taught at Williams until being called to be the University of Wisconsin as the Fifth President in 1874.

Bascom was an early proponent of the Social Gospel, the major progressive Christian movement of the late 19th and early 20th, of which my great-grandfather Walter Rauschenbusch was also a part. One of the foundational ideas behind the Social Gospel is that the kingdom of God, or Heaven, or Righteousness was to come, as we pray in the Lord’s Prayer, on earth realized here among us. As Rauschenbusch wrote: The kingdom of God is not a matter of getting individuals into heaven, but transforming the life on earth into the harmony of heaven.

Bascom is still a big name in Wisconsin. The university’s administration works in Bascom Hall, and the Bascom dairy on campus sells probably the best ice cream in the state. Likewise Charles Van Hise, the long-serving president of the UW is remembered with a hall where generations of students have studied foreign languages. People outside of Badgerland might be more familiar with Robert “Fighting Bob” LaFollette, founder of the Progressive Party in the early 20th century, and still today an inspiration to lefties.

![]() Enter to win a $50 Amazon gift card!

Enter to win a $50 Amazon gift card!

Click HERE to take our 2-minute reader survey.

LaFollette wasn’t a particularly religious man, but Bascom and Van Hise were, and so were many of the people who created the Wisconsin Idea: a broad vision of good government based on good information and good intentions making the world a progressively better place. As Raushenbush points out, there’s a lot of overlap between the Wisconsin Idea and the Settlement Movement of roughly the same era. Both shared a commitment to social betterment through pragmatic solutions, and both were more or less openly premised on the Social Gospel understanding of the good news as concrete service to society.

Alas, the moment did not last. Things fell apart during World War I and just before. LaFollette split the Republican party in 1912, leading to Teddy Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party, then opposed American entry into the war, causing his own movement to fall into mutual recrimination.

Nevertheless, Raushenbush thinks there’s something to be said for the Wisconsin Idea and its religious underpinnings:

Because we are in another moment of National Crisis and we do need inspiration. We are more polarized as a nation than I can ever remember. We are plagued by the twin evils of hate and fear, combined with violent rhetoric that threatens to fracture our society. We distrust and demonize one another and point fingers instead of extending a hand. Young black lives are criminalized, immigrant families are ripped apart and rounded up, refugees seeking a better life are banned based on religion, women continue to be subject to violence and denigration, suicide rates are spiking among working class whites, LGBT lives are trivialized, debated and legislated against, people of other faiths are targeted and demeaned, anti-Semitism is surging, millions are at risk of losing their healthcare and a budget was released today that builds up weapons and pays for them by cutting services to the poor, while income inequality is worse than it has been since the Wisconsin idea was first launched. We find ourselves constantly, intentionally pitted ‘us vs them’ and forget that there is ‘we the people’.

…

The first important principle of the Wisconsin Idea is that it is driven by vision. As is said in the book of Proverbs: “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” The vision of the early advocates of the Wisconsin Idea was inspired by the Christian vision of the Kingdom of Heaven on earth where justice and peace reigned. While this became less explicitly religious in subsequent generations it still was a vision marked by justice, equality, dignity and liberty for all no matter what religion, race, nationality, gender or sexuality.

In today’s America there is a very different vision that is competing with this inclusive and just legacy. To our great lament it is driven by our Christian co-religionists. White Evangelical Christians voted for Trump in huge numbers in a large part because they were fearful that they were ‘losing’ their country and they placed whiteness and nationalism over the Gospel. One of the most important task before us is to come up with a vision for Wisconsin and for the nation that is inclusive of all people and is more compelling than the one that is in power today. What world are we dreaming of and how can we invite everyone to share this dream?

And there’s the rub. There is no vision because in today’s politics, race is everything, even when it seems like it’s not. As fascinating as the history of the Wisconsin Idea is, the argument Raushenbush builds from it is incomplete, because it doesn’t include an analysis of how and why Republicans turned their back on their own legacy and now actively seek to undermine the very project they helped create.

I speak of Gov. Scott Walker, of course, and the modern WisGOP, who have been consistent foes of open government. They’ve pushed legislation in rushed hearings with little or no notice (most notoriously with the union-busting Act 10), refused to disclose donations or how they made plans for legislative redistricting, and sought to limit public input in the legislative process. Walker at various points has tried to cut the Legislative Bureau (responsible for collecting information and evaluating legislation), starved the UW System and the innovative Extension program that takes university learning into the community, and even remove the Wisconsin Idea itself from the university charter.

Walker’s base is in what has been called the “toxic racial politics” of the greater Milwaukee area, and this is no accident. Even abolitionists, as I’ve said before, may have been interested in legal equality between the races, but not necessarily social equality. Many of them favored “repatriating” freed slaves to Africa, or allowing them to establish segregated communities within the U.S. More to the point, when the Republican party first began, Wisconsin was almost exclusively white: only 1,171 free blacks were listed in the 1860 census, and just over 1,000 Native Americans, out of a total population of 775,000. The Republican-dominated government tried to keep it that way, with bills aimed at limiting black migration to the state.

I don’t mean to slander the early GOP, or the founders of the Wisconsin Idea; their politics really were radical for their day. My point is simply that it’s easy to push radical ideas in a homogeneous society. What we see over and over in American history, however, is that when the population becomes diverse, dominant whites will fight to deny anything like equal rights or benefits to minorities. This isn’t even a new phenomenon, nor is it limited to battles between races. LaFollette’s opposition to World War I devastated the Progressives in large part because it put him squarely on the side of the large German population of Wisconsin, who were often identified as another “race” and put under heavy pressure to assimilate into the dominant English-speaking society.

Today, the dividing line is more skin color than language. Scott Walker’s career is based on appealing to suburban and exurban voters’ belief that somebody needs to keep a lid on the hippies in Madison and the blacks in Milwaukee. His implacable hostility to the remnants of the Wisconsin Idea stems from his belief that the limits it imposes on extreme partisanship in the name of reason and progress are actually elitist means of keeping whites tethered to financial support for illegitimate and greedy special interests, such as unions and urban minorities. It is perhaps also not an accident that Walker is a committed, conservative evangelical.

Raushenbush is right that a vision is needed to overcome racialized partisanship. He believes that vision can be formed by bringing religious values into partnership with “new scientific facts, artistic wisdom and cultural knowledge” to fight “the denigration of knowledge”—or as we know it, “alternative facts.” Raushenbush also looks to citizens meeting to form a united vision for the common good and a commitment to the social good. It’s a sensible ideal for a university, where knowledge is developed, argued, and shared. And it’s well-rooted in Wisconsin history. If you go to downtown Milwaukee, for example, across the street from where they’re building the new Bucks arena, you’ll find Turner Hall, the former site of a German socialist athletic club. The old stained glass windows are still there, extolling the virtues of reason, science, freedom of inquiry, democracy, and a sound body.

But the organization itself no longer exists. Today, Turner Hall is a great place to catch a band or hold a wedding, but there’s nothing particularly socialist about it, unless you count a fine selection of microbrews as left-wing. In the broader communities, and even increasingly on college campuses, the light of reason and progress doesn’t shine as brightly as the irrational (and let us be honest) often stupid lens of racial resentment and hostility.

I’m not at all confident that specifically religious reason can bridge the gap, either. It’s true that religious movements often cross racial boundaries, but as PRRI’s Daniel Cox notes, there are simply fewer and fewer religious liberals interested in such things. The kids are increasingly secular these days, and they’re not so much interested in “transforming life on earth into the harmony of heaven” as shoving it down the bigots’ throats at the ballot box. Put more elegantly, they might agree that racism is America’s great spiritual disease, but the cure they propose is entirely secular: winning the contest of partisan politics.

To make matters just that much worse, many of the new secular voters see religion as the cause of partisan divisions, not the solution. They’re not particularly motivated by appeals to a better, more enlightened Christianity, because they’re not particularly interested in the religious project to begin with. The history of socially-engaged and inclusive Christian movements gone by cuts no ice. Our politics seems to be moving along with society into what Diana Butler Bass calls “Christianity After Religion,” with the Spiritual But Not Religious leading the charge against racial polarization. They seem to want to meet right-wing extremism with an equally strong progressive backbone. Beyond that, it’s anybody’s guess how it all plays out.

This, it should be said, is the best case scenario. The worst case is that already-common perception that “religious liberalism” is an oxymoron continues to spread and any kind of politics rooted in faith is pushed to the margins. We’re already at a point where religious symbolism fails to capture the imagination of the broader world of committed citizens. Pink pussy hats, for all their flash-in-the-pan-ness, are more motivational than clergy parading around in stoles and praying on the steps of some government building or another. Religious leaders either have to find a way to reinterpret their symbols for a new world, which is a daunting task, or find audiences willing to hear the current interpretation, which, you know, good luck on that.

I would sorely like to offer a more positive response to Raushenbush’s historically-minded optimism. (And not just him: I keep hearing the argument that labor and evangelicals could work together, because they did in the 1920’s.) I too would like to know how to make religious faith an asset to the broader progressive movement again. But the fact is, we find ourselves in an almost unprecedented situation, because our national understanding of faith and how it relates to social participation is radically different. What happened in Ripon in 1854—a rally around the social principles of a shared faith—almost certainly could not be reproduced today. Nor could the conditions responsible for creating the Wisconsin Idea. Looking at the history, that lesson seems obvious. What was radical yesterday isn’t often radical still today, and what’s radical today doesn’t very often stay that way for long.

1. This is contested, with other towns claiming to be the birthplace of the Republican party. Ripon has it documented.

2. The family simplified the spelling of its name along the way.