One of the most revealing exchanges of the second presidential debate came when the candidates stopped talking about current events and started talking about Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln came up after an audience member asked whether politicians can justifiably be “two-faced,” or whether they should present a single face regardless of the situation. In response, both candidates brought up “honest Abe.” This earned them plenty of ridicule—“I bet Lincoln would rather go to another play than watch this debate,” one person tweeted—but it also focused attention on the perennially vexed issue of hypocrisy and mendacity in the political realm.

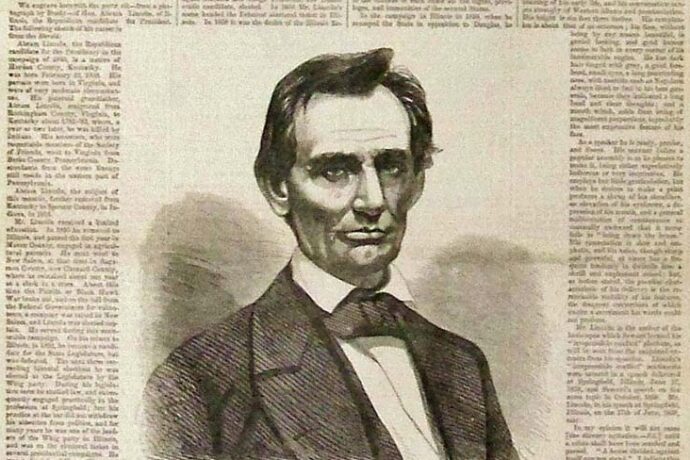

Trump invoked Lincoln’s time-honored nickname, “honest Abe,” as if it were unquestionably accurate, and as if it indicated a model any honorable politician should follow.

Meanwhile, Clinton drew from Steven Spielberg’s film Lincoln, which depicts a shrewd manipulator willing, under certain circumstances, to trim the truth in the service of a higher cause.

The difference between these two conceptions of Lincoln is revealing. By pausing to examine each of them, we may better understand the way mendacity normally functions in the political realm, and the ways in which, on some occasions, mendacity may violate the tacit rules that keep that system stable.

Lincoln’s reputation as a person of absolute integrity has been a staple of American political culture for many generations. Biographers have confirmed that Lincoln was, by and large, an exceptionally honest person. In one familiar tale, which was included in Horatio Alger’s 1883 semi-fictionalized biography Abraham Lincoln: The Backwoods Boy, Lincoln walked a long way to return a petty sum to a customer who had been inadvertently defrauded in a store where Lincoln then worked.

Despite his reputation, in his own day Lincoln was criticized by his opponents for lying. He could certainly spin the truth for political gains. The historian Richard Hofstadter included him “among the world’s greatest propagandists.”

An image of absolute honesty is, of course, a useful weapon in any politician’s arsenal, even if it is only an approximation of a more complex reality. In her invocation of Spielberg’s Lincoln, Clinton focused on a more shrewd, less familiar image of Lincoln. The particular episode in Spielberg’s film that caught Clinton’s eye was detailed in David Herbert Donald’s authoritative biography, in which the President denied the existence of peace envoys from the Confederacy in order to win Democrats’ support for the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude.

“As far as I know,” Lincoln told them, “there are no peace commissioners in the city, or likely to be in it.” In fact, as he knew, they were negotiating with his deputies at a spot just outside the city. Lincoln’s statement was technically accurate, but it illustrated his strategic reluctance to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, no matter what the cost.

Here Lincoln, we might say, was acting as a consummate politician. He realized that building coalitions often requires tactfully spinning the truth in order to win broad support for a laudable goal.

As Hannah Arendt wrote, without intending it as condemnation,

No one has ever doubted that truth and politics are on rather bad terms with each other, and no one, as far as I know, has ever counted truthfulness among the political virtues. Lies have always been regarded as necessary and justifiable tools not only of the politician’s or the demagogue’s, but also of the statesman’s trade.

In my book The Virtues of Mendacity: On Lying in Politics, I analyze some of the many ways that mendacity can be wielded for good as well as ill, depending on to whom the truth is owed, what the politician’s intention is in withholding the truth, and what the consequences of withholding it might be.

Politics is a realm of human endeavor that values plurality, takes opinion seriously, and knows the force of rhetoric. In that realm, it is probably impossible to achieve a singular, unambiguous truth that’s shared by everyone. Indeed, it may be lucky that such a goal is unattainable.

In this regard, Clinton is typical of her oft-maligned profession. She bends, shades, or spins the truth on numerous occasions, sometimes for reasons we might applaud, but at other times out of self-interest or a counterproductive penchant for secrecy (see the entry in her biography under “emails”). Here her husband may well have served as a model. Bill Clinton left such a long trail of tale-telling that Christopher Hitchens was able to title his 1999 denunciation of the president’s “triangulations” No One Left to Lie To, borrowing a remark made by the Majority Counsel of the House Judiciary Committee.

Hillary Clinton has managed to acquire a reputation that rivals Bill’s in the eyes of her detractors. But her tally is well within the norm for most politicians, even in a democracy with avowed norms of transparency and accountability.

Trump is a more complicated case. Part of his appeal for many voters is that he’s not a politician. He works hard to present himself as an authentic teller of uncomfortable truths, unshackled by the rules of civility and the constraints of what he contemptuously calls, without ever pausing to define it, “political correctness.” That is, Trump proudly calls himself a non-politician not only because he has absolutely no experience governing or legislating, but also because he fashions himself as a straight-shooting, uncensored vox populi, who eschews the hypocrisy and dissembling of the Clintons of the world.

There is some perverse validity to his self-description. Trump clearly lacks the coalition-building skills that a certain bending of the truth can abet. He is willing to insult those whose support might help him actually gain power. The link between politics and politeness—both of which draw on artifice to smooth over conflict—is one he both understands and repudiates. As suicidal as it has proven to be, his refusal to change his behavior to appear more “presidential” has a certain integrity to it, which his supporters, tired of the empty promises of traditional politicians, clearly find bracing.

But paradoxically, when Trump’s actual claims are subjected to fact-checking scrutiny, they often turn out to be far more vulnerable than Clinton’s. For all his fulminating against “lyin’ Ted” and “crooked Hilary,” Trump is in a class by himself when it comes to varnishing—or rather, vanquishing—the truth. And besides frequency, there are two salient differences between his relationship to lying and hers.

The first is a matter of scale. Clinton may be prone to defensive secrecy, rhetorical feints, and carefully worded denials. But by and large, her transgressions can be called “little lies” that don’t add up to the more audacious variety that came to be called “the big lie” during the era of totalitarianism. Big lies are designed to create an alternative universe in which memories of the past are discredited and new “facts” are concocted wholesale to replace them.

Trump does tell big lies. Among the most egregious is his claim that the “birther” conspiracy theory was originally Clinton’s doing, and that he deserves the credit for putting it to rest by compelling Obama to produce his birth certificate. Whereas a pluralist politics of countervailing spin, fibs, and occasional outright untruths can fuel the agonism that makes democracy an endless work in progress, the big lie is intended to put an end to bickering and corruption altogether, promising an entirely new form of metapolitical purity freed of any whiff of dissent or competition. In this, it is founded on perhaps the biggest lie of all: that an anti-politician asserting his authenticity and integrity can sweep the slate clean and return us to the days of lost greatness.

The second difference between Clinton’s and Trump’s approach to mendacity deals with the very nature of lying itself.

The fundamental structure of the speech act we call lying involves four distinct features: (1) the speaker knows or thinks he knows the truth. (2) He or she utters a deliberate falsehood, asserting the opposite of what he or she knows to be the case. (3) This false utterance is performatively designed to persuade the listener that it is true. And finally, (4) the lie can be called successful if it fools the listener. Typical politicians like Clinton conform, by and large, to this model whenever they varnish or warp the truth.

Trump seems to be different. It is not clear that he deliberately dissembles in order to persuade someone else of what he knows is not the case. On many occasions, he gives no indications whatsoever, even after the dubiousness of his claims are unmasked, of having actually harbored a private belief which is then contradicted by his public statements. For example, he seems to have genuinely believed that he watched thousands of Muslims celebrating after 9/11 on TV, or that he was an early critic of the war in Iraq, or that the Chinese created the global alarm over climate change.

For this reason, many commentators have invoked the philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s famous analysis of “bullshit” to describe what Trump does when he plays hard and fast with the truth. Unlike a liar, the bullshitter is ultimately unable to distinguish the difference between truth and falsehood and comes to believe his own claims no matter how exorbitant and far from reality they might be. In this sense, instead of having two faces, he only has one, in which there is no gap between interiority and exteriority, no cunning manipulation of appearance to mask what is an essential belief.

Trump seems unable to wear a mask. He cannot pretend to be what he is not. You can call this a mark of authenticity or of narcissism, perhaps even of delusional behavior. But it is definitely not normal politics in a democracy, in which it may well be not only efficacious, but justifiable, to resist the rigid moral imperative always to tell the truth.

* * *

Also on The Cubit: Politics in a fallen world