Of the 12 federal holidays, Columbus Day is one of only three celebrating a person. Among that trinity, which includes the celebrations of the births of George Washington and Martin Luther King Jr., it remains peculiar. Unlike the first president of the nation and the twentieth-century century civil rights leader, Christopher Columbus has only a tenuous connection to what became the United States. Although many of us were erroneously taught that “Columbus discovered America,” he never set foot on soil within our national borders and famously didn’t comprehend that he had encountered lands unknown to Europeans until his third voyage in 1498.

But by tethering their story to Columbus, early leaders of the United States magically endowed the fledgling nation with a three-hundred-year pedigree, a genesis story whose “in the beginning” implied its birth was the outworking of Providence. They invented a past that gave their present holdings, and their rapacious ambitions, the veneer of divine inevitability.

The sweeping power of this narrative strategy, however, lay not just in the epic voyages of Columbus, but in a religious doctrine he relied upon and indeed helped crystallize: the Christian Doctrine of Discovery. As Spain and Portugal ramped up their exploration and colonization efforts in the latter half of the fifteenth century, the self-described Christian kings and queens sought a moral mandate that would simultaneously address their obligations to newly discovered peoples and mitigate bloodshed between themselves.

They turned to the closest thing to international law that existed at the time, the Roman Catholic Church. In a series of papal proclamations between 1452 and 1493 (the last precipitated by Columbus’s return from his first voyage to the Americas), a new theology crystalized for the New World. While the theological constructions of the Doctrine of Discovery were complex, their logic was straightforward.

The principal question for determining whether any newly discovered peoples had human rights Europeans were bound to respect was this: “Are they Christian?” If the answer was negative, Indigenous people were categorized as “enemies of Christ” whose lands were subject to occupation and whose goods were subject to confiscation. If Indigenous people resisted the imposition of European authority, the new arrivals carried the permission of the crown and the blessing of the church to “reduce their persons to perpetual slavery” or to kill them outright.

Most of the controversy around the celebration of Columbus Day in the U.S. has focused on Columbus’s barbaric treatment of Indigenous people. These individual deeds are indeed appalling. But lionizing Columbus implicitly celebrates something much more systemic: the setting of the colonizer’s moral compass with European Christian supremacy as due north. This moral and religious orientation directed the entire settler colonist project: the genocide and forced removal of Indigenous people from their lands and the subsequent kidnapping and enslavement of Africans to transform those lands into profit producing plantations.

There is now a three-decades-old movement, initially led by Indigenous people, to replace the celebration of Columbus with a day honoring the original inhabitants of these lands. Indigenous Peoples’ Day was first celebrated in Berkeley, California in 1992 on the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus in the Americas. Since then, more than a dozen states and over 130 cities have adopted the holiday. In 2021, President Joe Biden became the first sitting president to issue an official proclamation of Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Amid rapid demographic changes—today only 42% of Americans identify as White and Christian—and cultural reckoning with the legacy of racism in our nation’s history, replacing Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day would represent a meaningful step forward. Columbus Day inevitably celebrates both the colonizer and the religious worldview that authorized the violence unleashed in his wake. But Indigenous Peoples’ Day points Americans forward toward our higher principles.

As President Biden said in his 2021 Indigenous Peoples’ Day proclamation:

“Our country was conceived on a promise of equality and opportunity for all people — a promise that, despite the extraordinary progress we have made through the years, we have never fully lived up to. That is especially true when it comes to upholding the rights and dignity of the Indigenous people who were here long before colonization of the Americas began.”

A federally recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day would simply be the right thing to do to honor our full history, our demographic present, and our democratic aspirations.

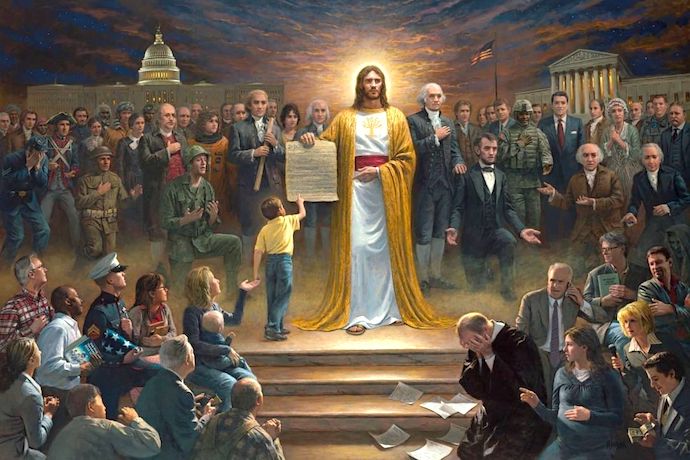

But there is another, more urgent reason we should embrace this change. The anti-democratic orientation of the Doctrine of Discovery still lives among us today. More than five centuries after its emergence, 30 percent of Americans, including majorities of Republicans and White evangelical Protestants, agree with its central tenet: that “America was intended by God to be a promised land where European Christians could set an example for the rest of the world.”

While contemporary analysts refer to this aggrieved and increasingly militant minority with the term “White Christian nationalism,” the roots of this threat to democracy reach back, before the founding of our Republic, to the Doctrine of Discovery.

Our nation has never fully answered this question: Are we a divinely ordained promised land for European Christians, or are we a pluralistic democracy where everyone, regardless of race or religion, stands on equal footing as citizens? If we’re to finally embrace our identity as a pluralistic democracy, we can’t abide an ongoing celebration of a worldview that erodes that commitment. But if instead we pause each year to honor Indigenous people alongside George Washington and Martin Luther King Jr., that observance will reorient us to the ongoing work of achieving the yet unfulfilled promise of our democracy.

This article was originally published on Jones’s #WhiteTooLong Substack. Read more here.