Pentecostalism, prosperity gospel, and a mining economy? Sounds like West Virginia, but here we’re talking about Zambia. In this RD10Q author Naomi Haynes shakes up some widely-held assumptions about the role of Pentecostal Christianity in social and economic life.

____

RD: What inspired you to write Moving by the Spirit?

Naomi Haynes: As a cultural anthropologist, my primary inspiration comes from the people I study—in this case, Pentecostal Christians who live in the Copperbelt province of Zambia.

I first went to the Copperbelt thinking that I would study language use in churches. However, very early on in conversations with Pentecostals it became clear to me that language wasn’t something they were particularly concerned about. As I was traveling around meeting pastors and laypeople, everyone wanted to talk to me about their economic concerns—about the prosperity gospel and the blessings they were hoping to receive from God, the difficulties of managing church and denominational budgets, and worries that pastors favored believers who had more money.

All of this was being worked out in a temperamental extraction economy, which has gone through several cycles of boom and bust since I first began working on the Copperbelt in 2003. This macroeconomic background made the microeconomics of Pentecostalism even more interesting, and I decided to make this religious/economic nexus the focus of my book.

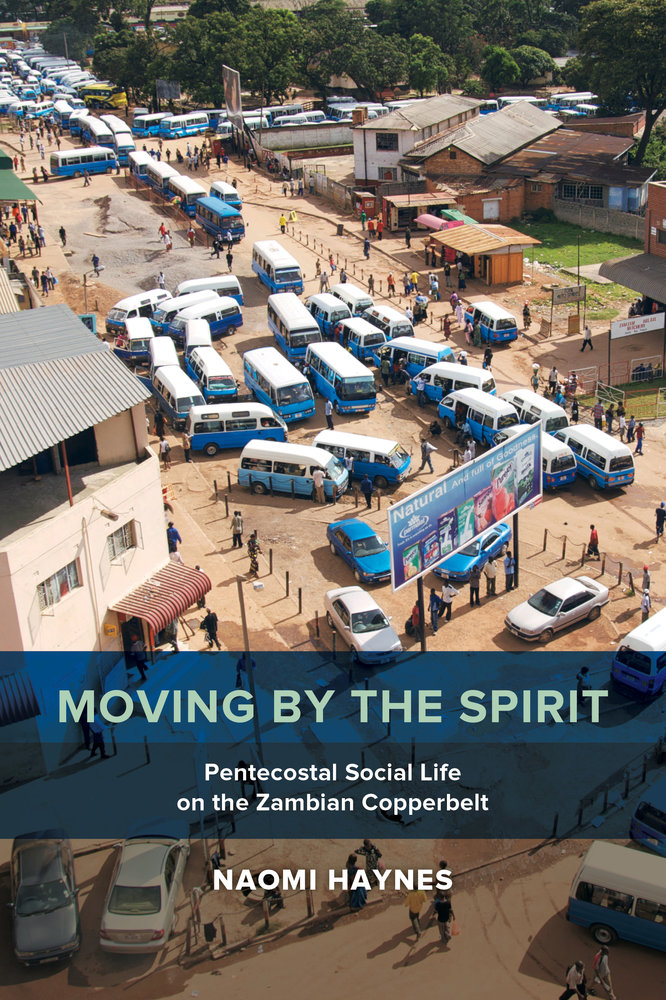

Moving by the Spirit: Pentecostal Social Life on the Zambian Copperbelt

Naomi Haynes

University of California Press

March 2017

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

The thing I would most like people to take from my book is that Pentecostalism helps make life possible, first and foremost by creating social relationships.

When I first began researching African Pentecostalism, the general consensus was that it was a religion for people who wanted to reduce their social obligations. There’s a way to tell the story of Protestantism more generally as an individualizing religion, and when this narrative meets the prosperity gospel, with its emphasis on conspicuous consumption, it was easy for scholars to paint a picture of Pentecostals as folks who wanted to avoid giving money to their kin so that they could have more to spend on themselves. I’m being a bit glib in this description, but the notion that Pentecostalism produces (or at least facilitates) relational breakdown is still common in social science.

I found something different in Nsofu, and my book tells that story.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

I’m a pretty merciless editor when it comes to my own writing (that’s one reason the book is so short!), and there was nothing that anyone other than me removed from the manuscript. If I were to add something else, I would want to explore more deeply how the relationships that form in Pentecostal churches mirror traditional kinship ties.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

I often hear people talk about African Pentecostal pastors as conmen, or at least people who have gotten rich on the backs of the poor members of their congregations. While there are some prominent preachers who do enjoy celebrity and fame, most Pentecostal pastors that I know are not making a lot of money.

During my fieldwork, I lived with a pastor’s family, and I watched them struggle to make ends meet. Their situation has changed over the years that I have known them, but that has had more to do with the pastor taking a job with an internationally funded NGO than with the offerings of parishioners. I think that if we tell the story of the prosperity gospel, and of Pentecostalism more generally, as a story of hucksterism, we miss a lot of what makes this religion so compelling.

Plus, we suggest that the folks who flock to Pentecostal churches can’t tell when they’re being duped, and after watching the how carefully believers dissect a pastor’s words, I don’t think that’s true.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

This is an academic book, and while I worked hard to make it accessible, the primary audience is other scholars interested in how religion and economics interact. I know the book is already being used in the classroom, and I hope that students will also enjoy reading it.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Entertain them? Piss them off?

My goal with this book is to challenge the way people think about popular religious movements, and specifically about how something like Pentecostalism shapes the way people interact with the world.

It’s not just that people turn to religion because other institutions or opportunities like the state or the market are breaking down. In other words, believers aren’t just compensating for some lack in their lives—another common misconception about Pentecostalism. Rather, they’re using religion to act in and on the world—that is, to make life possible.

What alternative title would you give the book?

I’ve never thought of this—I am terrible at thinking of titles and was rather pleased with Moving by the Spirit. Having to come up with something else is hard! In any case, the idea of “moving,” and the Pentecostal version of this, which is what I mean by “moving by the Spirit,” serves as an organizing motif for the book. So, the current title gives you a reasonable idea of what it’s about.

How do you feel about the cover?

I love it! So many books about Pentecostalism have covers featuring people in rapt worship, and I was really grateful to move away from that trope. My brother John, who is a photographer by profession, took the cover photo when he came to visit me in Zambia. I always find taking pictures difficult, so I was grateful to have someone there to do this work for me. I chose this particular picture for the cover of Moving by the Spirit because of how well it captures the metaphor of movement.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written? Which one? Why?

There are so many great books being written on contemporary Christianity. Nate Roberts’ To Be Cared For, which is in the same series as my book, is simply lovely. He gives the kind of intimate portrait of religious life and practice that I strive for in Moving by the Spirit.

What’s your next book?

I’ve recently been awarded funding from the Economic and Social Research Council here in the UK to return to Zambia. I’ll be looking at the religious and political implications of Zambia’s state-sponsored declaration that it is a “Christian nation”—the only one of its kind in Africa. In some ways, this is a scaling up of the work I did for Moving by the Spirit, as I’m continuing to explore the intersection of religion and public life, only this time at a national rather than a local level.