From his popular podcast, to his travels with Will and Jada Smith, to GAP ads with wife Radhi—the ones that feature his toothpaste-ad smile and eyes that rival that one famous National Geographic cover—it’s hard to escape Jay Shetty. He is beloved among celebrities and his motivational talks frequently make the rounds on social media, but many have also found his platitudes eye-roll-worthy and his story about his monk past suspicious. A recent exposé on Shetty by the Guardian’s John McDermott expertly dives into his past, accusations of plagiarism, and his certification course, but in the author’s effort to discover the higher truth of Jay Shetty, McDermott, like so many other detractors, misses one essential element of his popularity—Orientalism.

Critiques of Shetty have tended to focus on poking holes in his story of monkhood in an attempt to unmask him as a fake self-help guru profiting off of vulnerable people. Although this focus is justified, it fails to acknowledge the larger problem: Shetty is only successful because he is giving us exactly what we want in the exact form we want it.

In Edward Said’s seminal work, Orientalism, he argues that the construction of the East is always a reflection of Western anxiety and desires. Sometimes the East is seen as barbaric and superstitious in contrast to the West as scientific and civilized. Other times, the West is dismissed as too materialistic and individualistic, lacking the spiritual depth found in the East. Transcendentalists, like Ralph Emerson and Henry Thoreau; Beat Generation writers like Alan Watts and Jack Kerouac; and popular figures like the Beatles have all turned to the East to provide a spirituality assumed to be missing in the West. Even Elizabeth Gilbert in her memoir, Eat, Pray, Love, accomplishes the “pray” portion of her title in Bali.

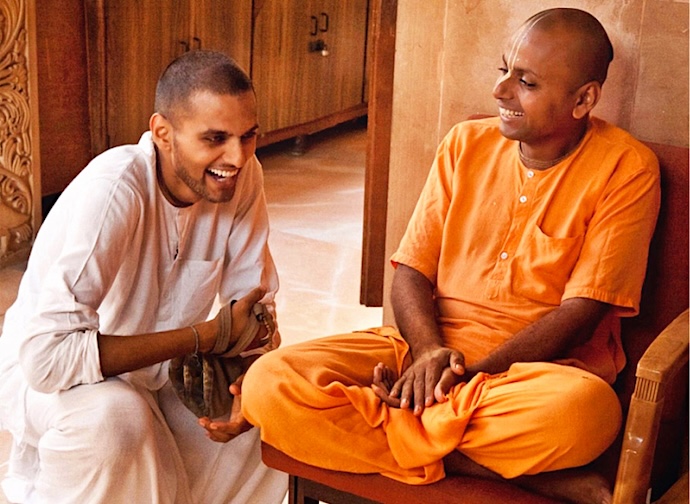

Shetty is among the latest in a long line of “wise men from the East” who’ve found success in translating the “wisdom” from the East into the “language of the West” without the bothersome trappings of their particular cultural contexts. These “oriental monks” have traditionally accentuated their foreignness through their physical appearance—orange robes, “Eastern clothing,” long beards, etc.—as well as an aura of peacefulness.

Part of their appeal comes from their claims to have distilled the true essence of Eastern religions. No need to label anything or separate it as “Hinduism,” “Buddhism,” “Jainism,” etc. because they’ve extracted the “Truth,” which gets lost in all the messy cultural stuff, disguising the insights and benefits—the core. And access to the core is exactly what we desire. This also gives us an easy explanation for why those in the so-called “East” don’t seem to be fulfilled despite having access to these philosophies—it’s been “corrupted” by the unnecessary rituals, rules, and regulations.

Although Shetty is British, he legitimizes his authority by citing his time spent in India. The accuracy of this claim is less important than the story he tells. His admirers don’t need proof of where in India he went or how long he stayed, because the image of India and spirituality is so intertwined that any amount of time spent there is enough to transform your life and worldview.

Shetty has retained the soft voice and the aura of the calm oriental monk, but he’s ditched the beard and robes for a clean-shaved face and trendy, stylish clothing in an attempt to appeal to those in the market for a “modern” guru-figure—one who looks like them but seems foreign enough to access the secrets of the East. Shetty presents his spirituality in hazy terms because that’s all his followers want and require. The use of a term like “Vedic” is enough—it’s foreign, sounds ancient, and feels “authentic.” When actor Dax Shepherd, in defense of his podcast episode on Shetty, identifies Shetty as an “expert in religions from India” without explaining what religions or how he’s an expert, he reveals what all Shetty’s followers desire—a nondescript “Eastern-ness.”

Although it may seem that Shetty avoids mentioning his background in ISKCON (better known as the Hare Krishna movement) because of controversies the group has faced in the US, I would argue that there’s another reason for this omission. ISKCON is too familiar. The fact that many would have encountered them on city corners or on college campuses makes them simultaneously foreign and not foreign enough. Shetty keeps his relationship to the group quiet because it’s not integral to and perhaps even distracts from the vague “Eastern spirituality” he seeks to represent. It is precisely that vagueness that appeals to Western seekers since it grants you permission to access spirituality without needing to really change anything. You can be in the world and enjoy all of the pleasures of capitalism without being of the world.

But the fact that we’re attracted to this caricature of Eastern spirituality isn’t Shetty’s problem, it’s ours. It’s a waste of time to evaluate and critique Shetty’s authenticity as though the revelation that he’s problematic or a phony would diminish his appeal. Authenticity is ultimately about us and what we want to experience. In his 2005 book on urban blues clubs in Chicago, David Grazian writes: “authenticity itself is never an objective quality inherent in things, but simply a shared set of beliefs about the nature of things we value in the world.”

Arguments both for authenticity and claims of authority can help us understand which ideas a culture values most. Uncovering the truth about Shetty’s life loses its power once we realize that he isn’t some unique figure. Instead, we might reorient our gaze and ask what his popularity reveals about us and the persistence of Orientalism that allows figures like Shetty to become successful time and again.