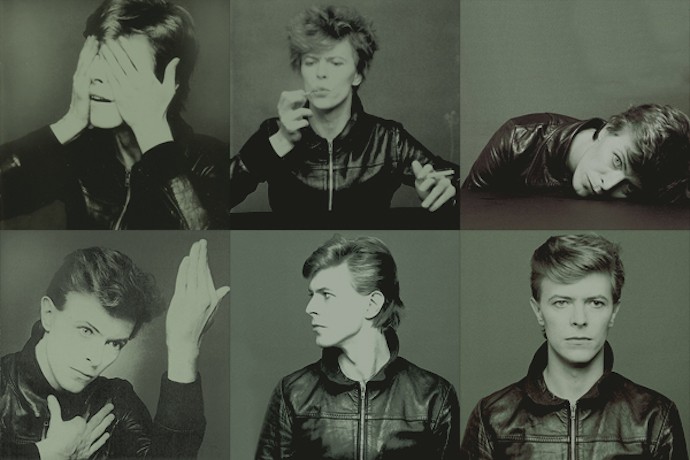

It’s almost stranger to think that there ever could have been a David Bowie than that he is no longer here. He seemed more like ten different performers, ten different musicians. That he cleaved together such multiplicity for such a long time seems hard to fathom. And yet many of us awoke this morning, shocked to see the tributes to the somehow-more-than rock star that died today, only three days after the release of his last album.

Cynics can smugly have their cringes of superiority when the public collectively mourns the death of celebrities; Bowie was fucking great, his passing deserves our tears. If Bowie made life not just tolerable, but luminescent for the gay kid in the rural Midwest or for the art-school girl in northern England then by every right they are allowed to light a candle for the man who fell to Earth. It’s a heartless fucking world; let’s not begrudge people when they’re able to find a little bit of heart in it.

Cynics can smugly have their cringes of superiority when the public collectively mourns the death of celebrities; Bowie was fucking great, his passing deserves our tears. If Bowie made life not just tolerable, but luminescent for the gay kid in the rural Midwest or for the art-school girl in northern England then by every right they are allowed to light a candle for the man who fell to Earth. It’s a heartless fucking world; let’s not begrudge people when they’re able to find a little bit of heart in it.

As writer Peter Bebergal, author of Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll, said in a Facebook post this morning, listening to Bowie during a particularly difficult time in his life reminded him that “life could still be full of beautiful weirdness, magical art, and maybe even a little decadence.”

Bowie was paradoxically completely liminal and somehow also at the center of things. His music and many personas were proof of Rimbaud’s assertion that “I is an Other,” or Bob Dylan’s claim that “I wake up and I’m one person, and when I go to sleep I know for certain that I’m someone else.” If the self is a tapestry of influences, a bit from here and a bit from there, ever changing, mutable, mercurial, then Bowie simply demonstrated to his listening public that all of us are legion.

Bowie was a master of both surfaces and depths, forever changing and altering his understanding of self and its relation to the rest of us—always reinventing. He did this of course not just with music but also fashion, gender, art, and—a fact often glossed over—religion.

His spiritual interests were promiscuous. He explored everything from the I Ching to Zen Buddhism, to Aleister Crowley, to his own brand of ritualistic and performative mysticism embodied in that alien rock ‘n’ roll messiah. As he said in a 2005 interview with Anthony DeCurtis: “Questioning my spiritual life has always been germane to what I was writing. Always. It’s because I’m not quite an atheist.”

In this way Bowie was representative of that sort of theological freedom through which the most interesting questions can be asked, and possibly through which some of the most interesting answers may be found. He is a model for taking what we need and leaving the rest; a type of can-do pragmatism and religious anarchism.

There will be many lists of Bowie’s greatest songs in the next few days; no doubt your social media feeds are already collectively curating a soundtrack. Certainly his 1977 classic “Heroes” (co-written with Brian Eno) will be the favorite of many. [See video for “Heroes” at bottom of post.] In a career so expansive it’s impossible to definitively label any track or album as the absolute greatest, but “Heroes” exemplifies what precisely about Bowie so many of us loved. Composed while Bowie was kicking his drug habit and recorded in West Berlin just a few hundred miles from the Wall, he claimed to have been inspired by an anonymous couple he saw from his window.

Beneath a triumphant Wall of Sound the singer tells us about this pair of nameless lovers who meet for trysts next to that other Wall, this symbol of conflict, division, and totalitarianism. In “Heroes” the narrator “will be king” and his lover “will be queen.” For Bowie, their love is both an act of resistance and a sacrament. The guards in their turrets will presumably see this small defiance, and yet the couple “can beat them” even if “just for one day.”

We may be crushed everyday by systems not of our own invention, by ideologies not of our own choosing. But a gesture of love in front of the Berlin Wall is still an act of resistance, letting the bastards know they can’t completely grind you down. Politics really is personal, and resistance is too. These things matter. They have to.

“Heroes” is a profoundly religious song, because it’s about the power of rituals, of actions, of the transcendent hiding in the material—of freedom in a kiss. It is “religion” (with a lower case “r”), the faith that sets men and women free—the sound of rock ‘n’ roll.