The media is abuzz this week with the revelation that Justice Antonin Scalia died while on a hunting expedition with several prominent members of a 300-year-old Bohemian secret society, the Order of St. Hubertus. The owner of the hunting lodge where he passed away is a prominent member of this order, as was Scalia’s traveling companion.

The order’s motto “Deum Diligite Animalia Diligentes” means “Honoring God by honoring His creatures.” There’s certainly a bitterness to the notion of “honoring” God’s creatures by killing them—and the Order’s practice of donning traditional European hunting attire and shooting captive-raised pheasants and partridges adds injury to that insult.

In the case of the Order of St. Hubertus, though, there is an extra layer of irony to explore. The legend of St. Hubert, champion of sport-hunters, was based in the sacred stories of a tradition that ultimately condemned the killing of animals.

How the morality of a Buddhist legend was turned upside down in its Christian re-telling is a story that bears lessons of its own.

Origins of the Hubert Legend

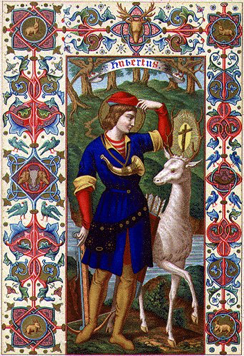

St. Hubert is the Germanic patron saint of hunters and fishers. He is perhaps most famous as the Jägermeister (“Master Hunter”)—the basis for the stag-crucifix emblem of frat-party legend. The legend of Hubert describes him as an impious eighth-century aristocrat who flouted religious duty by hunting on Good Friday. In pursuit of a magnificent stag, he is interrupted and admonished by the stern voice of Christ in the presence of the majestic deer, and witnesses a radiant vision of the crucifixion in the animal’s enormous horns.

In repentance for his sins, he renounces his worldly ambitions, is ordained, and subsequently lives a pious life of solitude in the forest where he then has his faith repeatedly tested.

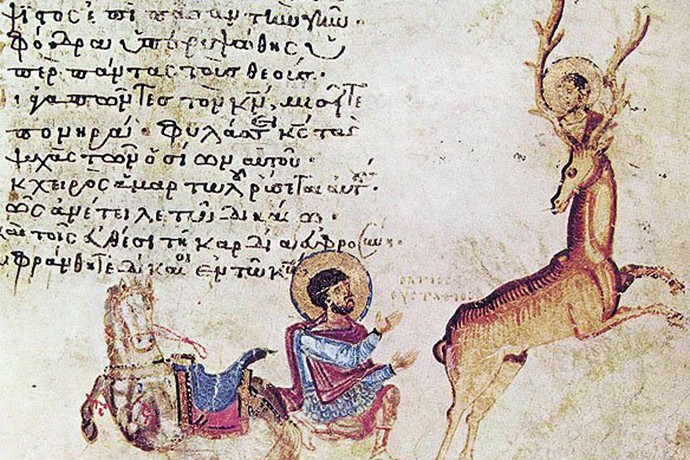

Virtually the same legend is attributed to an earlier Roman saint, Eustace (née Placidus), set in the second century. In that version, the protagonist is a pagan general in Emperor Trajan’s army on the Asian frontier of the Roman Empire, likewise converted by Christ in the form of a fleeing deer.

But in an intriguing example of the migration of religious myth, the single biography of Hubert/Eustace is now believed by many scholars to be a Christianized synthesis of two famous Buddhist legends.

The first act of the story is based on an eighth-or-ninth century Syriac translation of the first-century Nigrodhamiga-Jātaka, the legend of King Brahmadatta of Benares and the Banyan Deer. Here the Hubert/Eustace character is the great King Brahmadatta. The Bodhisattva (future Buddha) is the majestic King of the Deer. The animal Bodhisattva’s horns radiate silver light and the deer’s eloquent speech compels this erstwhile hunter king to become a champion of the dharma of the Buddha.

The second act of both hagiographies is a Christianization of the Visvantara-Jātaka, with Hubert/Eustace now cast in the role of the Bodhisattva himself. (Visvantara is famously the penultimate incarnation of the historical Buddha.)

Some have raised the possibility that the Buddhist-Christian parallels are coincidental, insisting instead that the narrative is derived exclusively from the Book of Job. However, the strongest proof of the Indian origins of these texts is not merely the fact that they share a common plot. It is the telltale use of a South Asian place name: Hydapses (Jhelum in Panjab). It has been persuasively argued that the anachronistic setting of the Eustace legend far beyond the Syrian borders of Roman Asia links the narrative conclusively to the Buddhist originals.

Furthermore, there was a straightforward historical process for the synthesis of Christian and Buddhist canonical texts within classical Manichaean monasteries of the Silk Road.

Mani was a third-century ascetic Persian prophet who was born of a Christian family but regarded Gautama Buddha as a previous incarnation of Jesus Christ. Mani’s followers redacted Buddhist narratives under the rubric of Western theology. Saint Augustine was the most famous ex-Manichee, and Manichaeism for Western Christianity is regarded (since Augustine’s time) as a contemptible heresy. Nonetheless, Manichaeism was the most successful Gnostic Church in history, and enjoyed a degree of state support in Central Asia at precisely the right moment to act as a permeable “membrane” between Buddhist and Christian monastic cultures.

At the same time, a flood of heterodox clerics from Asia Minor and the Balkans were re-introducing old heresies (known as neo-Manichaeism) to the mercantile cities of the Mediterranean coast, springboard to the Silk Road. This phase of European history led ultimately to the Albigensian crusade and the horrors of the inquisitions, as the official Church fought these heresies tooth and nail.

It was around this time that four or five different popular Christian saints were born of Buddhist originals: Hubert, Eustace, Barlaam (Bagavan in Sanskrit), Josaphat ( Bodhisattva), and likely also St. Christopher. These stories were all translated into most European languages, and were ultimately bound together in Jacobus de Voragine’s late medieval bestselling novel, The Golden Legend. Thus several of the most popular saint’s biographies of Medieval Europe were translations of Buddhist Sanskrit!

Why does this matter?

The great popularity of Buddhist Jātaka narratives is not confined to any particular sect, because as models of exemplary religious ethics, these stories did not primarily address doctrine or dogmatic creeds. The narratives were theological “blank slates” and could be redacted to include dogma, but they didn’t contain too many “red flags” which identified them as coming from a competing doctrinal system. Thus the same stories are found in a wide range of Buddhist schools and medieval Christian denominations (both orthodox and heterodox). So Manichaean Buddhist/Christian texts could easily be stripped of any problematic or heretical connotations.

This is what happened, it is believed, to the Hubert legend, as it was gradually transformed and the original ethical implications were turned on their heads—an act of cultural misappropriation by the medieval Church, ever concerned with combating so-called “Manichaean” heresies.

Thus what had originally been a condemnation of all forms of sport-hunting, came eventually (for the Order of St. Hubertus), to be a strange endorsement of sport-hunting as an act of reverence toward animal life.

Brahmadatta was an aristocratic sport hunter. The deer were in his private game reserve, and were subject to death based on a lottery system. The king was a vain pleasure hunter who had no need to kill for subsistence. In explicit terms, Brahmadatta was like the members traditionalist hunting club which includes so many of Scalia’s friends and associates in Washington high society. He did not eat meat to sustain life, but as an expression of his affluence and thirst for adventure, which was maintained under the pretense that the “sport” was real.

In reality, the doomed deer merely performed their duty for noble king’s pleasure.

When the Bodhisattva convinced the monarch of his error, he adopted the great Buddhist lay-precept “do not take life,” and officially decreed the end to the practice of sport hunting throughout his entire kingdom.

Manichaeans were closer to orthodox Christians in terms of theology and prophetology, but closer to Buddhists in terms of religious ethics and animal life. This is why the particular redacted Jātaka tales almost invariably address themes of human-animal interaction. The original Manichaean-Christian hagiography of Eustace was set in Pagan Rome, a century or so before the time Augustine and Mani. But the Pagan Roman narrative context was generally a time of Manichaean-Christian solidarity. By the late third century, Manichees and Christians were grouped together and severely scapegoated.

The Eustace legend is thoroughly Christianized in theological terms, but the ethical imperatives are more faithful to the Buddhist originals (and to Manichaean ethics). Eustace is converted by the charismatic deer itself, speaking directly to the saint as a physical manifestation of the Cosmic Christ. Eustace’s major sin is threatening to harm Christ in the form of a deer (evoking Matt 25:40). The animal expounds Christian doctrine in plain speech (just as the Bodhisattva-as-deer expounds Buddhist doctrine). Finally, Eustace is martyred for refusing to eat meat sacrificed to the emperor, harmonizing Christian theological mandates against idolatry with Manichaean mandates for vegetarianism.

The historical context for the “Hubertus” redaction of the same story is very different. Unlike Eustace, Hubert’s grave sin is not sport hunting per se, but sacrilegious sport, refusing to perform the Stations of the Cross on Good Friday. The deer itself is a “dumb animal” and does not speak to Hubert. Rather, Christ’s voice is a disembodied sound in the presence of the deer. The deer does not instruct Hubert directly, but Christ appoints Hubert to the care of human tutor (St. Lambert) who acts in place of the deer. The martyrdom and idolatrous animal sacrifice, so prominent in the Eustace version, are conspicuously absent here.

We can understand these changes as revisions by more theologically orthodox scribes in the tenth century or later, when a concern with combating resurgent Manichean doctrines was extended to the subtlest ethical precepts. Monks were even occasionally asked to slaughter animals to prove to their superiors that they lacked heretical sympathies. Hubert’s biography has been purged of the ethical vestiges of the Sanskrit and Syriac source materials, facilitating its use by those who endorse sport hunting.

Some Buddhists are vegetarians, but others are not. Subsistence hunting (never pleasure hunting), is acceptable within the Buddhist world, where meat-eating may be a matter of survival, e.g. in the Himalayan uplands.

The order’s motto—“Honoring God by honoring His creatures”— is in fact very close to the ethical precepts of the Manichean-Buddhist synthesis. Faithful devotion to these principles of stewardship and creation-care could not be labeled cultural misappropriation, even for a hunting club. But insofar as the Order currently supports the killing of caged birds for the pleasure of affluent citizens (rather than dispassionately culling a herd to sustain the life of the poor), the Order is practicing animal “conservation” in a way that is starkly anathema to the spirit of the ancient text upon which the Latin motto is faithfully based.

And to the extent that high ranking officials in the Order of St. Hubertus are also high ranking members of groups like the Safari Club (notoriously culpable in the destruction of endangered African mammals), the Order has misappropriated and undermined the ethical precepts of the sacred text at its core.